By Ashley Peele

Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax © Alex Shipherd

Leaves are turning gold and frost covers the grassy fields here in the mountains of southwest Virginia. Drab little Cape May and Tennessee Warblers flit through the tree lines, while streams of Common Nighthawks track southward through the river valleys. These heralds of Autumn signal a finale that was hard to imagine nearly five years ago, when the VA Dept. of Wildlife Resources (formerly, Dept. of Game and Inland Fisheries), the VA Society of Ornithology, and Conservation Management Institute at VA Tech launched the second VA Breeding Bird Atlas. Taking a brief pause to breathe deeply and consider the last five breeding seasons, the project prepares for a dive into review of the mammoth database built through our volunteer community’s data collection efforts. However, prior to outlining these next steps for the VABBA2, let us step back and reflect on the course of this project, which has brought it to such a successful conclusion.

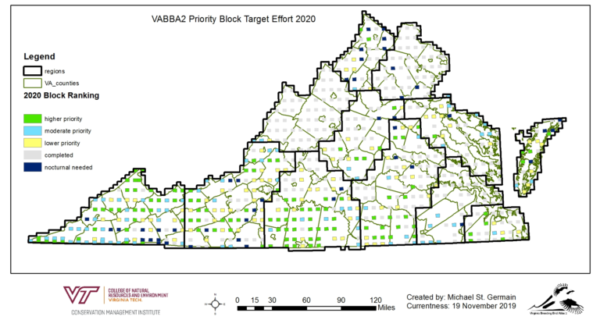

Project Priorities at the start of 2020

At the start of this effort, Atlas project goals focused broadly on finding and training, you(!), the volunteers needed to pull off a statewide breeding bird survey. Fortunately, through the efforts of our network of project partners (bird clubs, Audubon societies, master naturalists), volunteer regional coordinators, and your individual responses to statewide calls/meetings/training sessions for birders, the project had over 1200 contributors across the Commonwealth by the end of 2019. Given the success of these efforts, two key goals remained at the start of 2020…

- Filling the Gaps – several key gaps in the spatial coverage of breeding bird data remained at the end of 2019, thus getting volunteers or technicians into these areas was a key priority. An initial map published this Spring illustrated where the largest gaps in coverage remained (Figure 1).

- Surveying all incomplete priority blocks – This goal was two-fold and included both

- The completion of priority blocks that already had some breeding bird data reported

- Survey coverage of priority blocks with little to no data, prior to this field season.

Figure 1. Map of VABBA2 Block Targets – 2020. Color scheme indicates both the priority level assigned to incomplete priority blocks, as well as blocks needing only nocturnal effort.

Our strategies for meeting these goals relied heavily on our volunteer community, especially folks who were able/willing to collect Atlas data in the southern Piedmont and southwestern mountain-valley regions. Additionally, the 2020 field efforts relied heavily on field technicians (primarily college students or recent graduates) whose blockbusting efforts were funded by a grant from the Virginia Society of Ornithology.

Impact of Covid-19

A review of our final field season wouldn’t be complete and accurate without acknowledging the impact that covid-19 had on this year’s efforts. Like every wildlife data collection project across the nation and world, we devoted April and much of May to assessing if and how the project might move forward this year. There were a couple inevitable impacts on this season – 1) a delayed start to birding for our field technicians and many volunteers; 2) the cancellation of more than half of our planned Atlas events.

Fortunately, many volunteers were still able to find ways to safely get out and collect data by early June. A couple things were in our favor… first, that birding can easily be a solitary activity. While it may be more fun to bird in groups, many of our volunteers adapted to ‘solitary’ birding for the sake of collecting data. Second, our target areas were in largely rural regions, which allowed volunteers to avoid interacting with other members of the public. Obviously, all of this required an adjustment to the usual protocols – e.g. always driving their own cars, avoiding close group outings, putting off travel requiring hotel stays, etc. – and yet it worked! The project managed to reach all areas targeted for breeding bird surveys this summer.

Given how bleak things looked around mid-April, we have to thank all of our volunteers who persisted in finding ways to safely collect data this summer. We were up against a challenging new set of conditions, which you helped us to work through. To past volunteers who were unable to participate this year, we also want to thank you for all your work in those past seasons. The pandemic has brought changes and challenges to all our lives and we appreciate the folks who had to make tough, but necessary decisions to protect their own health and/or that of their loved ones.

While our final season was impacted by covid-19, this year marked only one of five great seasons of collaboration, community, and collecting data for the conservation of VA’s birds.

So, How Did We Do?

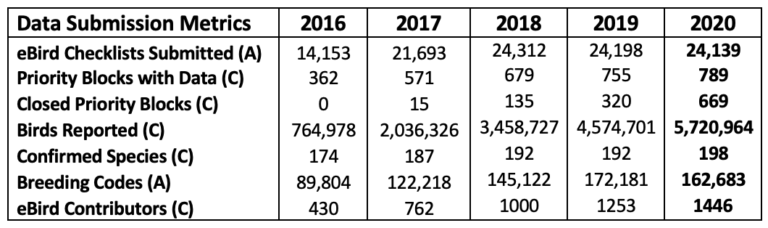

For this final field season update, we’re going to take a slightly different approach to past years and illustrate the overall progression of our efforts, since 2016. First, for the numbers geeks amongst us, check out Table 1, which illustrates some key data metrics for each year of the project. If you do a little addition, you’ll note that we ended the project with over 108,000 checklists submitted to the Atlas eBird portal! Within these checklists, volunteers reported nearly 700,000 breeding codes and documented over 5.5 million birds. Our ability to use eBird as a tool for data collection has obviously been a game-changer for collecting bird data, but you don’t build a database of this magnitude without also having a dedicated community of volunteers.

Table 1. Annual eBird Data Summary for 2016-2020 Field Seasons – (A) denotes annual figures; (C) denotes cumulative figures. Note: checklist counts now include checklists for which observers indicated that not all individuals were counted.

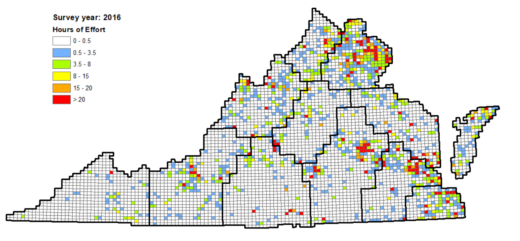

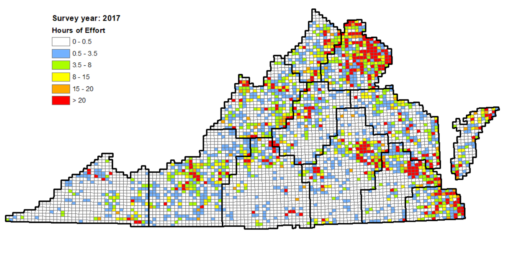

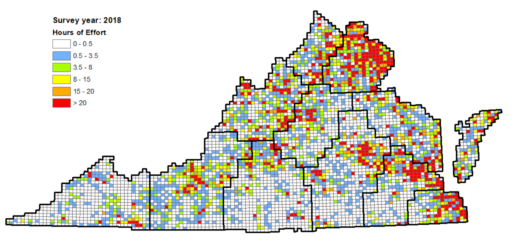

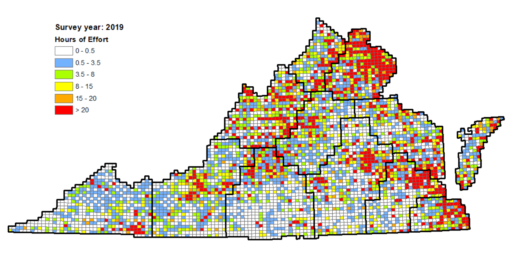

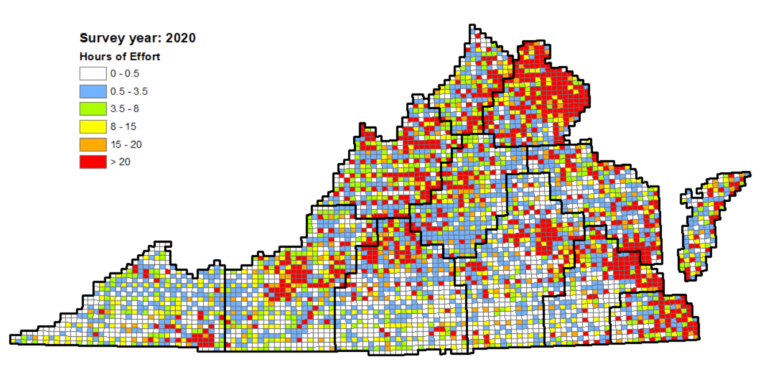

Now, for the map lovers amongst our readers, we’re about to throw a lot of fun visuals at you. The numbers shown in Table 1 are interesting to consider, but seeing the visual progression of our data collection can offer some interesting insights. The following series of maps illustrates the spatial distribution, as well as the intensity, of breeding bird data collection from 2016-2020.

Figures 2a-6e. Distribution of Cumulative VABBA2 Effort – illustrated by hours of effort per block for each year from 2016-2019.

Figure 2a. 2016 Cumulative VABBA2 Effort

Figure 2b. 2017 Cumulative VABBA2 Effort

Figure 2c. 2018 Cumulative VABBA2 Effort

Figure 2d. 2019 Cumulative VABBA2 Effort

Figure 2e. 2020 Cumulative VABBA2 Effort

A few interesting things to note… First, as we’ve written about in the past, the earliest areas to receive Atlas effort were those closest to our largest cities. Logical, right? More people usually means more birders, which results in more data! As the project progressed, effort spread out into more rural regions and slowly began to fill in the gaps. However, Virginia has huge areas of the southern Piedmont and mountain-valley region with few people and even fewer birders, in contrast to regions like Northern Virginia or Virginia Beach. These areas took special effort by both field technicians and Atlas volunteers who were able/willing to travel to remote corners of the state to collect data. Some folks did this through participation in Atlas rally events hosted at VA State Parks, others organized their own trips and ventured into areas of the mountains or piedmont previously unknown to them. If you’re interested in hearing more of their stories, check out our back catalog of Atlas articles!

Comparison with the first VA BBA

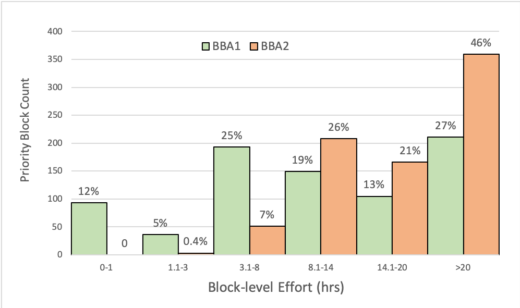

For the sake of evaluating how we did in this 2nd VA BBA, it is interesting to look back and compare our modern efforts with historic data. Since priority block coverage is a key focus for every BBA, we used the hours of birding effort logged in each priority block to compare BBA1 and BBA2. More specifically, we lumped effort hours into six categories, then looked at how many priority blocks fell into each effort category (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of priority block effort in VA’s first (BBA1) and second (BBA2) atlases. Note that bars illustrate the total # of blocks in a given effort category with percentages provided at the top of each bar.

In BBA2, priority block effort shifted strongly toward the higher effort categories with ~97% of priority blocks receiving at least 8 hours of effort from 2016-2020, compared to 59% from 1984-1989. And importantly, BBA2 had far fewer blocks with less than 8 hours of effort. While the most rigorous block completion protocols shoot for at least 15-20 hours of effort, eight hours of breeding bird survey time typically lead to a solid species list and a basic understanding of the breeding bird community present in a given block, making this an important threshold for data collection.

Species Highlights

While a deep-dive into the species data will be forthcoming next year, a few interesting species highlights stood out this field season. First, thanks to both volunteer and field technician efforts, Pittsylvania and the surrounding counties received a huge surge in Atlas data this summer. Nesting ravens were found in this county, a very eastern record for the southern piedmont, contrasting with a westernmost breeding record for Mississippi Kites, found near the same area of Pittsylvania county.

Prothonotary Warbler carrying food – Bill Wood (https://ebird.org/atlasva/checklist/S70793475)

In the mountain-valley region, the westernmost record of a probable breeding Prothonotary Warbler was documented near Abingdon with the westernmost confirmation for this species found along the New River in Giles county. Detections of breeding Virginia Rails continued to increase in southwest Virginia, highlighting the value of searching small wetlands and pond areas for these secretive species. Many high elevation breeders found over the border in West Virginia have proved difficult to find and confirm in VA’s western mountains, but this summer the elusive Purple Finch was finally confirmed breeding in Highland county, near Locust Springs.

Volunteer Recognition

The volunteer community that has arisen around this project is, quite frankly, one of its most important accomplishments. Growing from a few hundred to over 1400 contributors speaks to Virginia birders’ commitment to not only birding, but birding for conservation. I’ve used this phrase many times over the course of this project and it is not a concept that all birders or wildlife viewers ascribe to. Yet, what more important thing can be done with our birding data than putting it toward the active management and conservation of the species we love? This is the fundamental idea that Atlas volunteers have supported with their time, funds, and energy.

We hope to eventually acknowledge all of the 1400+ volunteers who have contributed to this project. For now, there is a group who stand out for both the volume and dedication of their Atlas data collection efforts that we’d like to take a moment to recognize. Their contributions are not limited to the metrics used here, but those included in Table 2 (see end of article) reflect the scope of their efforts on behalf of this project. Note: Volunteer names are listed alphabetically within each table.

Virginia Rail Fledgling – David Boltz (https://ebird.org/atlasva/checklist/S30710131)

Additionally, we want to particularly acknowledge a number of dedicated individuals, including many volunteer regional coordinators and veteran Atlasers, who participated in a group dedicated to blockbusting. These folks worked with myself and each other to focus their efforts on geographic areas of greatest need and those that were unlikely to receive effort from local volunteers or field technicians. Their efforts and persistence were critical to carrying the project over the finish line and conveniently, they are also all named above.

For all those whose names did not make it onto one of these lists, we value you and whatever time you’ve been able to give to this project. As we progress through the next phases of the project, we hope to highlight more and more of your efforts.

Speaking of Next Steps…

What comes now that five years of data entry are completed and we’re left with this colossal dataset? Not surprisingly, the next phase of the VABBA2 project will be a deep-dive into data review and cleanup, supported by continued funding from the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR). While a coarser level of data review has occurred on an annual basis, this next phase will include a much more refined evaluation of the existing dataset, as well as incorporation of many ancillary datasets collected by project partners and collaborators over the same time period (2016-2020). These additional datasets will help to fill gaps in survey of specific habitats (e.g. marshes), species (ex. Golden-winged Warbler) and/or regions where additional data may prove helpful (e.g. National Forests). This data review process is scheduled to launch in earnest this January and is expected to take around a year to complete.

Once data review is complete and the final raw Atlas dataset is in hand, the data analysis and modeling phase of the VABBA2 will begin, again through funding by DWR. Projected to take approximately 1.5 years, proposed Atlas analyses include:

- Distribution and occupancy modeling of current breeding bird populations

- Assessment of change in distributions, since VA BBA1

- Modeling of bird population density for various species, as well as estimation of their current population sizes in Virginia

Working with DWR, our goal is to continue updating our volunteer community on both the status of the VABBA2 review and analysis, as well as new citizen science opportunities that may arise in future years. We value the tremendous impact that our strong volunteer network can have on regional wildlife monitoring and ultimately, hope to provide more and more opportunities for you to play a hands-on role in the conservation of Virginia’s birds.

| Table 2. VABBA2 Volunteers who ranked in the top 50 statewide for one or more of the following categories: (a) most completed checklists, (b) blocks with confirmed species, and (c) total confirmed species | |||

| Top-ranked Categories | Volunteer | Top-ranked Categories | Volunteer |

| a-b-c | Becky Keller | a-c | Ira Lianez |

| a-b-c | Bob Epperson*+ | a-b | Janice Frye**+ |

| a-b-c | Candice Lowther | a-b | Kent Davis |

| a-b-c | Carlton Noll | b-c | Kim Harrell |

| a-b-c | Conor Farrell | a-b | Laura Mae |

| a-b-c | David Larsen | a-b | Lewis Barnett*+ |

| a-b-c | Diane Holsinger | a-b | Nick Newberry |

| a-b-c | Donna Mateski de Sanchez | a-b | Phil Kenny |

| a-b-c | Ellison Orcutt*+ | c | Alan Williams |

| a-b-c | Evan Spears*+ | c | Amiel Hopkins |

| a-b-c | Fred Atwood | c | Aylett Lipford |

| a-b-c | Garrett Rhyne** | c | Baxter Beamer |

| a-b-c | Guy Babineau*+ | c | Bill Williams |

| a-b-c | Harry Colestock | c | Cade Campbell** |

| a-b-c | James Fox+ | a | Claire Kluskens |

| a-b-c | Jason Strickland | c | Cory Taylor |

| a-b-c | Jeff Blalock | a | Diana Doyle |

| a-b-c | Joe Girgente | c | Diane Lepkowski |

| a-b-c | John Spahr*+ | a | Erin Chapman |

| a-b-c | Kelly Krechmer+ | c | Ezra Staengl |

| a-b-c | Kurt Gaskill*+ | c | Greg Moyers |

| a-b-c | Laura Neale+ | c | John Pancake+ |

| a-b-c | Logan Anderson** | c | Lisa Rose |

| a-b-c | Matt Anthony | c | Mark Johnson+ |

| a-b-c | Rob Bielawski | c | Matt Gingerich+ |

| a-b-c | Shawn Kurtzman** | a | Phil Lehman |

| a-b-c | Steve Johnson+ | c | Rochelle Colestock |

| a-b-c | Susan Babineau+ | a | Shea Tiller |

| a-b-c | Todd Day | c | Theo Staengl |

| a-b-c | Ty Smith | c | Wendy Richards |

| a-b | David Clark | *Volunteer regional coordinator | |

| a-b | David Ledwith | **Volunteer & Field Technician | |

| a-b | Don Mackler** | + Volunteer Blockbuster | |

| a-b | Drew Chaney* | ||

| a-b | Hannah Wojo** | ||