By CPO Eric Dotterer/DWR for Whitetail Times

Seasoned hunters are not immune to the gut-wrenching feelings of defeat. Whether it be missing a shot at a big buck, finding out a prized deer was harvested on a neighboring property, or worse yet, losing one to a vehicle in the road. While these moments in time may cause heartache, they pale in comparison to what a hunter feels when he or she see the results of poaching.

Consider the situation of spending an entire pre-season scouting the buck of a lifetime. The trail camera takes picture after picture of this nocturnal giant. Then, one night, a shot echoes through the silence, and that buck of a lifetime is never again captured on camera. Days turn to weeks and feelings of wonder are replaced by doubt as thoughts of being cheated by an unethical hunter start to grow and fester.

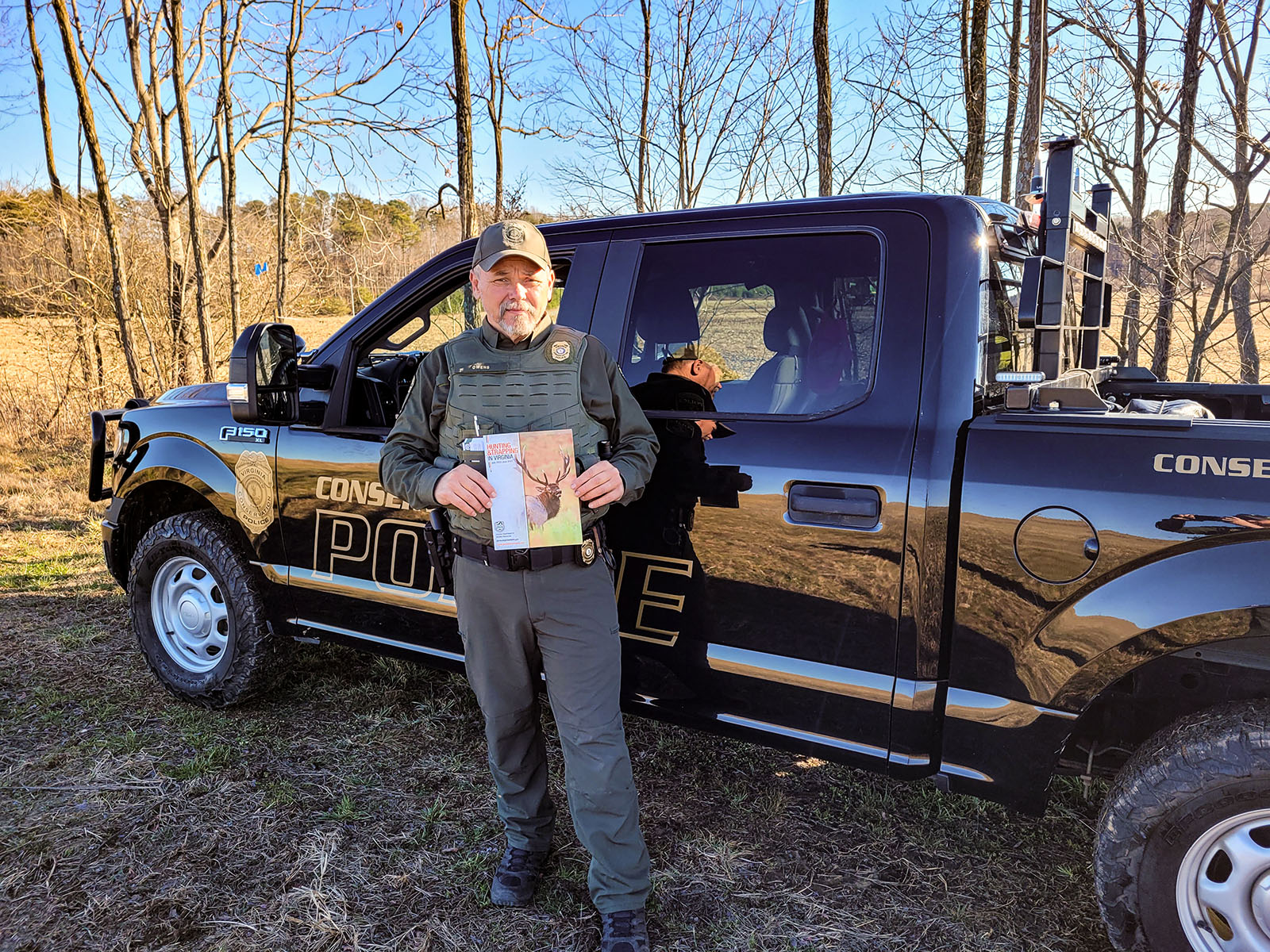

In Patrick County, Senior Conservation Police Officer Dale Owens tackles this recurring problem on the front lines. His story details how excellent police work and a good eyewitness can succeed in bringing poachers to justice.

Getting the Tip

One cold November night during general firearms season, CPO Owens was conducting a spotlighting patrol on a long narrow rye field in the flat lands of Patrick County. The night was nearly black as Owens positioned himself behind an old barn and watched vehicles slowly drive down one of the many roads that cross the Virginia line into North Carolina. A vehicle approached and tapped its brakes. Owens readied himself for the possibility of a chase, only to watch the vehicle move on as a call from a local resident came in on his phone.

The homeowner was woken by a gunshot, and from his bedroom window he witnessed a pickup truck sitting in the middle of the road before it quickly left the scene. Owens began the 45-minute drive through deserted, two-lane mountain roads. As he neared the area, he studied his surroundings for suspicious vehicles or evidence.

Once on scene, he was met by a visibly upset homeowner who had remained vigilant at the house, waiting for the vehicle to return. From the porch, the homeowner recounted the incident and described the best way for the officer to enter the property. Owens proceeded to the incident location and continued his search for evidence. Approaching the narrow dirt road that the homeowner had described, he travelled towards the middle of the property using night vision gear to evade detection. Upon reaching a location that offered a tactical advantage, he exited the vehicle and began to walk the hayfield using his handheld FLIR (Forward Looking Infrared) to look for heat signatures that would resemble a fallen deer.

A FLIR can assist CPOs in many different scenarios, such as in a search and rescue, apprehending fleeing suspects, and locating dead or injured wildlife.

About 150 yards in, Owens entered a knee-high soybean field dampened by the night’s dew. He then noticed an SUV, approximately a quarter of a mile in the distance on a paved road, presenting clear indications of illegal behavior. The vehicle had topped a small hill in the road and ceased to move, its headlights fixed. Moments later a second light appeared, making the trademark sweeping motion from left to right over a grassy section of field.

Immediately, Owens returned to his vehicle, keeping watch over his shoulder as he ran. Hitting a stride at 100 yards in, he heard the distinct crack and pop of a high caliber rifle pierce the silent night. Owens turned but could no longer see lights nor the vehicle. In double-time, Owens arrived at his vehicle and proceeded to the blacktop. With over a mile between them, he feared that the suspects may have had time to escape.

Making the Case

Once the dirt turned to pavement, he traveled in the direction he had last seen the suspects. In the distance, a pair of headlights approached his vehicle. As the vehicles met in the road, Owens locked eyes with the driver and saw an all too familiar look, and he knew he had his violator. He quickly turned his patrol vehicle to pursue the suspect. A quarter mile later, Owens caught up with the suspect’s vehicle and was able to call in the tag to dispatch. He noticed the presence of a second person when the vehicle voluntarily pulled off to the shoulder of the road. His sixth sense was on high alert as he reached down to activate the emergency equipment. The blue and white lights turned night into day while Owens wondered if the suspects had willingly complied or were preparing an ambush. He called in his location and turned on his take-down lights as he exited his patrol vehicle, knowing backup could take 45 minutes to arrive.

CPO Owens checks his MDT (Mobile Data Terminal) for calls in the district. The MDT can also be used to check DMV and DWR license information as well as vehicle status.

He approached the vehicle on the passenger side and, in case the worst happened, made sure to leave a critical fingerprint on the back-quarter panel of the suspect’s vehicle. With his EagleTac flashlight in his left hand and right hand on his firearm, he made his first sweep of light to illuminate the rear cargo area of the SUV. The light revealed hair and antlers peeking out from under a tarp. He cautiously approached the back-passenger door window. With another sweep, he located a third person partially hidden with a blanket laying down on the rear bench seat. His keen eyes were also drawn to the butt of a rifle barely visible from beneath the same blanket. In an instant, he reacted with a stern, commanding voice and ordered the passengers to keep their hands where he could see them.

Owens advised the rear passenger to slowly remove the blanket. He was surprised to find a scared woman in her pajamas. After confirming no other firearms were in the vehicle, he secured the rifle and started to obtain identifying information from the passengers. As he relayed the occupants’ information to dispatch, Owens was relieved to see the headlights of another patrol vehicle. Owens briefed the Patrick County Sheriff’s Deputy and directed the driver toward his vehicle for questioning.

On the way, they stopped at the back hatch of the SUV. The driver opened the door for Owens to inspect the deer hidden underneath the tarp. To his surprise, a second buck was revealed when the tarp was lifted. The man lowered his head then quietly continued to the patrol vehicle. Owens placed the suspect in the front passenger seat. The two sat silently; the man unaware that the officer to his left had been an Investigator earlier in his career and excelled in various interview techniques. Owens waited, choosing to allow the silence to work to his benefit. The driver began to speak, and the entire story unfolded.

Owens applied the same technique with the other two passengers and pieced together a detailed account of the night’s illicit activities. The shooter had met with the driver and the rear passenger, the driver’s wife, at their house. The couple had passed on a night of pizza and TV and instead, had used a babysitter to spend that quality time illegally harvesting deer. The front passenger would kill the deer, while the driver would check it in using his North Carolina hunting license. The thrill seekers had already killed one deer in North Carolina before killing a second deer in the Virginia field that Owens was investigating. They loaded the deer and continued down the road. After obtaining all the details, Owens opted to issue multiple summonses. He confiscated the firearm and the night’s trophies in lieu of an arrest and vehicle seizure.

The Virginia hunting and trapping regulations – available in print and online – are the most important equipment for any hunter. They should be carefully studied prior to any hunting excursion.

This story not only highlights the uniqueness of a Conservation Police Officer’s obligation to serve, but also conveys how a witness is able to assist in bringing a poacher to justice. A few helpful tips that can change the course of an investigation:

- A good witness should notify DWR dispatch immediately when a crime occurs. Conservation Police Officers want to know when a shot is heard at night, a vehicle is seen casting a light, or if evidence of a deer kill is found. Every minute matters in an investigation.

- A good witness gathers accurate information such as vehicle descriptions, direction of travel, exact occurrence times, and number of shots. To avoid confusion, use a camera phone to collect evidence of a possible crime.

- A good witness does not disturb the scene nor attempt to locate evidence on their own. The crime scene enables the responding officers to piece together elements of a crime. Contaminating the scene may alter or destroy crucial elements such as tire tracks, footprints, and scent, making it more difficult for the officers to complete an investigation. Well-intentioned witnesses have stepped on shell casings and lodged them into the ground, added unnecessary odors to a trackable scent, and walked around incident scenes deterring a suspect from returning.

- A good witness gathers information safely and helps an officer create the best case.

CPO Owens concluded his investigation by alerting a North Carolina Wildlife Officer of the information on the deer harvested illegally in North Carolina. The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission obtained charges and the suspects were found guilty. They were also found guilty in the Patrick County Court and ordered to pay fines.

Master Conservation Police Officer Eric Dotterer set a goal of becoming a game warden by age 8 and spent his early years working at a hunting preserve located near his home. In 2007, he graduated from Tennessee Technological University with a degree in Wildlife and Fisheries Management and was hired by Virginia’s Department of Wildlife Resources later that year. After the academy, he was assigned to Pittsylvania County and continues to serve the area.

©Virginia Deer Hunters Association. For attribution information and reprint rights, contact Denny Quaiff, Executive Director, VDHA.