By Andrea Naccarato/DWR

Butterflies are fascinating creatures to observe in Virginia’s natural ecosystems, gardens, farms, and any other places where they can flutter from flower to flower. This article provides a brief introduction to butterfly biology and spotlights a few of Virginia’s common species. Future articles in this series will describe opportunities for you to further connect with butterflies, including participating in butterfly surveys and creating butterfly habitats.

Classification

Within the Animal Kingdom, butterflies are considered a type of insect because they have three pairs of legs and an exoskeleton. Within the insect group, butterflies’ closest relatives are the moths. The group that includes both butterflies and moths is called “Lepidoptera,” meaning “scale-wing.”

Lifecycle

Butterflies go through four major stages during their lives. For three out of those four stages, they don’t look anything like butterflies!

Stage #1 – Egg

Every butterfly life begins inside a tiny egg, about the size of a pinhead. Adult female butterflies generally lay their eggs on young leaves of specific kinds of plants, called “host plants.” Depending on the species, the eggs may appear in various colors, shapes, and textures. Using a magnifying lens helps one appreciate the beauty of these easily overlooked eggs.

Stage #2 – Caterpillar

A wingless, worm-like creature called a caterpillar (also referred to as a “larva”) is what hatches from the egg. Its head is equipped with jaws that are perfect for munching the young leaves and other soft parts of its host plant. Caterpillars move around and cling to their host plants using three pairs of true legs (near the head) and additional pairs of “prolegs” (near the rear end).

Eastern tiger swallowtail in caterpillar phase. Photo by Shutterstock

The caterpillar generally does not bear any resemblance to the butterfly it will become, although the caterpillar’s appearance changes drastically as it grows and sheds its skin multiple times. Depending on the species and growth stage (called an “instar”), caterpillar skin may appear translucent, camouflaged, colorful, or even spiky. Eventually, the caterpillar will find a safe location, hang upside down, and shed its skin one final time to reveal the third stage of its lifecycle: the chrysalis, also known as a “pupa.”

Stage #3 – Chrysalis

The chrysalis is often affixed to a plant stem or other sturdy structure, although some species’ chrysalises may be hidden in fallen leaves. The chrysalis may display eye-catching colors, like the jade green and metallic gold of the well-known monarch chrysalis, or they may blend in with surrounding dead leaves. Although the chrysalis is stuck in place, sometimes they can twitch suddenly to scare off potential predators!

Stage #4 – Adult Butterfly

After a few weeks to months of undergoing impressive bodily changes inside the chrysalis, a recognizable adult butterfly emerges. The fresh butterfly typically hangs by its legs off the remains of its chrysalis while its wings expand and it prepares for flying.

Butterfly Appearance

Adult butterflies (hereafter simply called “butterflies) have three main body sections—head, thorax, and abdomen.

Photo by William Coward

There are three obvious features of a butterfly’s head:

- Two long antennae with club- or hook-shaped tips

- Relatively large compound eyes

- A coiled tongue (called a “proboscis”)

The proboscis, which looks like a tiny fishing line when unrolled, functions like an elongated sponge to absorb flower nectar or other nutritious fluids.

As is true of insects in general, butterflies have three pairs of legs, although “brushfoot” butterflies stand on only two pairs of legs. (Their first pair of legs are reduced in size, covered in bristles, and perform sensory functions.)

Wings

Butterflies have two pairs of wings, one larger pair attached near the head (called “forewings”) and one slightly smaller pair to the posterior (called “hindwings”). Both pairs of wings are covered with microscopic, colorful scales. The impressive patterns and seemingly artistic designs that can be seen on butterfly wings are extremely useful when trying to identify species.

Butterfly observers talk about distinguishing marks seen on the wings “above” or “below.” This distinction matters because butterfly wings can look very different depending on which surface of the wing is in view. If a butterfly rests with its wings spread open like a book, the observer sees the top or “dorsal” side. Other butterflies tend to perch with their wings closed vertically, leaving the bottom or “ventral” side visible. (In this pose, the smaller hindwing appears in front of the taller forewing when viewed from the side.)

Many butterfly field guides include useful pointers drawing your attention to certain colors, shapes, or other distinguishing marks to help you identify a given species. See the Resources section at the bottom of this page for some recommended field guides.

Families

Six families of butterflies live in Virginia:

- Swallowtails

- Whites and sulphurs

- Gossamer wings (blues, coppers, and hairstreaks)

- Metalmarks

- Brushfoots

- Skippers

Species Spotlights

According to the website Butterflies and Moths of North America, more than 170 species of butterflies have been recorded in the Commonwealth. The following species spotlights will introduce you to five butterflies that are common across Virginia. These descriptions will focus on the adult stage. Some of the Resources listed below provide caterpillar descriptions/photos.

Eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus)

Eastern tiger swallowtail. Photo by Andrea Nacarrato/DWR

This large yellow butterfly with black tiger stripes is Virginia’s state insect. There is one teardrop-shaped tail on the bottom of each hindwing, which is characteristic of most swallowtails.

The eastern tiger swallowtail may appear in two forms—the yellow form and the black (or “melanistic”) form. The melanistic form of this swallowtail occurs in females only and is believed to function as a survival strategy. This darker version of the eastern tiger swallowtail appears to mimic the pipevine swallowtail, which is toxic to predators.

Eastern tiger swallowtails can be found throughout Virginia in a variety of habitats. Females lay their eggs on the leaves of several types of trees, such as tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera), wild cherries (Prunus sp.), and ash trees (Fraxinus sp.)

Clouded sulphur (Colias philodice)

A clouded sulphur. Photo by Shutterstock

The clouded sulphur is a medium-sized yellow butterfly with several look-alikes. The clouded sulphur can be distinguished from its sunnier cousin (the cloudless sulphur) by black smudges along the rims of its wings when viewed from below. Plus, there are charcoal-black borders outlining the clouded sulphur’s wings on the topside, which may be seen during flight.

Another look-alike is the orange sulphur, a western species with a relatively recent arrival on the east coast. The orange sulphur may be even more frequently seen than the native clouded sulphur. How to tell them apart? If it looks just like a clouded sulphur with a splotch of orange on the forewing below, it’s probably an orange sulphur! (Keep in mind, females may appear white for both these species.)

Clouded sulphur caterpillars may eat a variety of herbs in the pea family. Although the widespread non-natives white clover (Trifolium repens) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) are commonly listed as examples, there are also dozens of native plants in the same family that could serve as potential hosts for this butterfly.

Eastern tailed-blue (Cupido comyntas)

Eastern tailed-blue. Photo by Andrea Naccarato

Despite its small size, the eastern tailed-blue is one of the most commonly seen butterflies across Virginia. This butterfly is so frequently seen on butterfly surveys that participants simply shout out its initials “ETB” whenever one is encountered.

It is often easier to view the underside of their wings, as eastern tailed-blues usually perch with their wings closed. The underside appears pale gray with black spots, two of which are bordered by a flame of orange. The namesake blue color, which is brighter on males, is only seen when the butterfly opens its wings to bask or fly.

Female eastern tailed-blues lay their eggs on the flower buds of plants in the pea family, such as ticktrefoils (Desmodium sp.) and bush clovers (Lespedeza sp.).

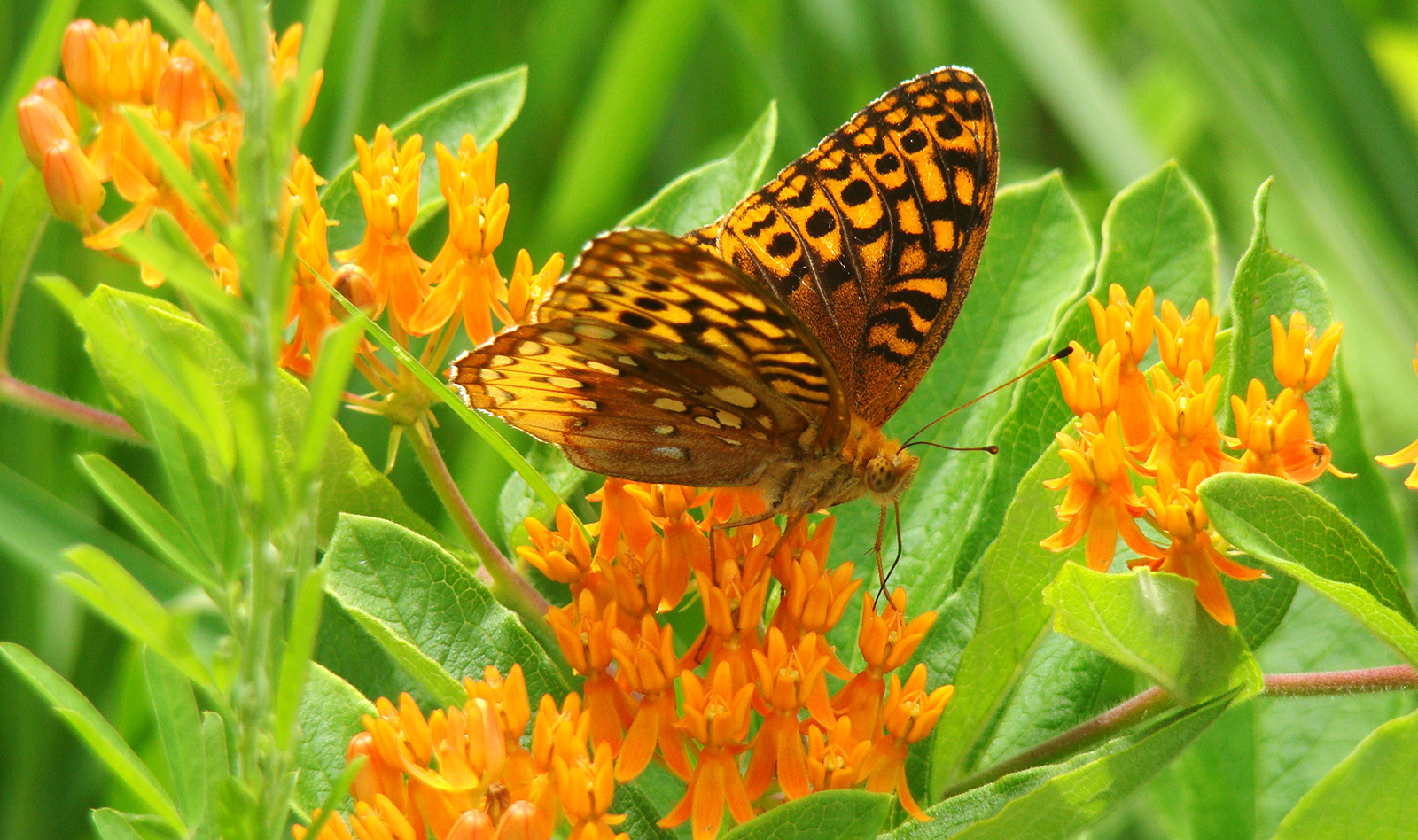

Great spangled fritillary (Speyeria cybele)

Great spangled fritillary. Photo by Andrea Naccarato/DWR

The great spangled fritillary is hard to miss. About the size of a monarch, this is a large, orange butterfly with intricate black patterns on the wings above and large, silvery-white splotches below. The top side of the wings tends to be darker closer to the butterfly’s main body segments.

This eye-catching brushfoot typically lands on bunches of small flowers (such as common milkweed [Asclepias syriaca]) and takes its time drinking nectar, making it very cooperative as a photo subject. Sometimes, they will even share a cluster of flowers with multiple (often smaller) butterfly species.

This fritillary may spend a lot of time around milkweeds, but that is not its host plant. Great spangled fritillary females seek out violets (Viola sp.) to feed their progeny. Sometimes, the females lay their eggs close to—rather than directly on—violets, meaning the newly hatched caterpillars may have a bit of journey before enjoying their first host plant meal.

Silver-spotted skipper (Epargyreus clarus)

Silver-spotted skipper. Photo by Andrea Naccarato/DWR

Although even experienced butterfly surveyors can be stumped by skippers, the silver-spotted skipper is one of the easiest to identify. Besides being relatively large, this dark brown butterfly has a noticeable silvery-white splotch on the underside of its hindwings. This distinguishing feature is prominent even at a distance, especially on sunny days.

Skippers are named for their quick, direct flight patterns, giving the impression that they suddenly “skip” from one place to the next. It is not unusual to be surprised by a skipper appearing out of nowhere, only to disappear a moment later. This behavior is one reason why skipper identification can be a great challenge for experienced butterfly watchers.

The silver-spotted skipper is the third butterfly on this list that lays eggs on plants in the pea family. Besides a diversity of herbaceous peas, this skipper also selects young foliage of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia). Caterpillars hide within their own leaf shelters when not feeding.

This has been a brief introduction to the wonderful world of butterflies in Virginia. There are so many more species out there! The next time you venture out in the spring or summer, keep your eyes out for these beautiful animals. Besides brightening your day, their presence is extremely important to natural processes from food webs to pollination. Future articles will focus on things you can do to support the conservation of butterflies in Virginia.

Andrea Naccarato is the DWR Outreach Production Assistant. During her first summer living in Virginia, she participated in eight butterfly counts that ranged from the Coastal Plain to the Blue Ridge.

Resources

Books/Field Guides:

Butterflies of the East Coast, An Observer’s Guide by Rick Cech and Guy Tudor. 2005. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Butterflies of the Eastern Chesapeake: Maryland, Virginia & Delaware, Pamphlet by Arlene Ripley. 2017. Quick Reference Publishing, Inc. Pocket-size & waterproof.

Butterflies of the Mid-Atlantic States, Pamphlet by Arlene Ripley. 2018. Quick Reference Publishing, Inc. Pocket-size & waterproof.

Butterflies of the Mid-Atlantic: A Field Guide, by Robert Blakney & Judy Gallagher. Independently published.

Websites:

Alabama Butterfly Atlas (includes plenty of Virginia species)

Atlas of Rare Butterflies (and more) in Virginia, by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation

Butterflies and Moths of North America

“Growing Eastern Tiger Swallowtails and Other Wildlife”

Nectar and Host Plants for Selected Mid-Atlantic Butterflies and Moths

Piedmont Environmental Council’s Larval Host Plants of Selected Lepidoptera