By John Page Williams

Photos by John Page Williams

Wildlife. Habitat. That’s what the Pamunkey River is about, and the Department of Wildlife Resources’ (DWR) Lester Manor public landing is a great departure point for exploring it. An old friend joined First Light and me for a day at the beginning of summer.

We arrived at the Lester Manor landing at high tide, which reminded me that this ramp has a more gradual downward slant than most of DWR’s other facilities. It requires backing a trailer further than usual, which means, for my rig at least, that all four of the tow vehicle’s tires were in the water as well as the trailer’s. Fortunately, this ramp is far enough upriver that the Pamunkey is fresh here except in extreme drought, so damage from salt is minimal.

The ramp does, however, demand cautious use, including a skipper’s willingness to wade wet or wear hip boots in launching or retrieving a trailered boat. That said, passengers can board easily from the adjoining dock with ladder, which is especially useful as the vertical tide change can be as great as 3.5’ on a full or new moon. It’s worth checking NOAA’s Lester Manor current table as well, since the water can move as much as 1.0-2.5 knots in either direction. Building an itinerary around it is especially important for paddlecraft.

We headed downriver first, noting that Lester Manor is also known on some maps as White’s Landing. Other long-established but private landings also have served Pamunkey Native people and local farmers for literally a thousand years. The tidal Pamunkey flows through deep meander curves from the Route 360 bridge all the way down to its mouth at West Point, scouring out deep holes on the outsides of the turns while building wooded swamps and huge marshes on the insides, the latter full of seed-bearing plants like wild rice that produce giant food banks for migratory waterfowl and other birds. Some of the river’s tributary creeks have strong enough flow that they drove mills in colonial times, grinding grain into flour that farmers could ship out directly from their landings.

We turned briefly into one of them, Cohoke Creek, following two anglers in a bass boat practicing for a weekend tournament. A large creek like this one commonly has a shallow mouth created by sediment forming a bar where its downstream flow meets the river’s current. The channel coming out of the creek will tend to lie on the downstream side of the mouth, but entering still requires caution and a willingness to use a pushpole if necessary. Inside, Cohoke’s channel drops to as much as 8’ in turns, but it’s important to follow the outsides of the curves alertly, as the channel’s shoulders are shallow. In any case, this creek is lovely, with tidal freshwater marsh full of seed-bearing plants like wild rice, smartweed, tearthumb, and rice cutgrass. Old stumps sprout blooming rosebushes. We stopped briefly to drift with the Merlin Bird ID app running on a smartphone to record bird sounds. Three minutes captured songs from fourteen species, including the lovely prothonotary warbler.

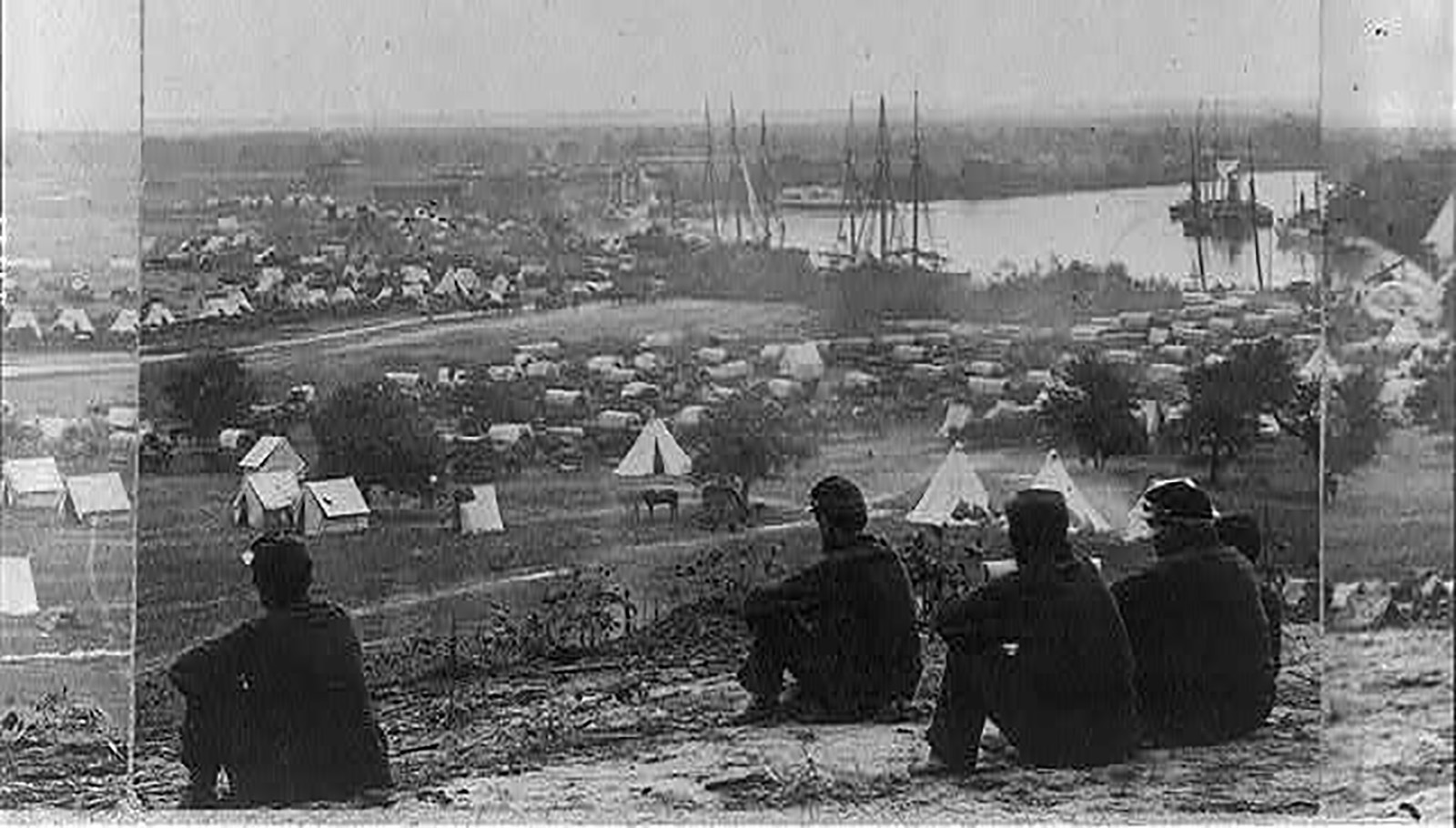

We eased back out of Cohoke Creek into the main river, with a mature bald eagle flying parallel to us, and ran down past Cumberland Landing, a hairpin turn through which the whole Pamunkey watershed drains. The deep holes we saw on the skiff’s sonar and powerful eddies on the river’s surface reminded us that some of this water had fallen as rain as far west as Orange and Gordonsville, at the western edge of Virginia’s Piedmont. Cumberland was an important river wharf for many years in the 17th and 18th centuries for shipping, and in the 19th for steamboats. During the Civil War’s Peninsula Campaign in 1862, it served as a camp for the Union Army.

Cumberland Landing during the Civil War. Photo courtesy U.S. Library of Congress

Today, part of the property is a private estate, part a specialized hospital for adolescents, and part The Nature Conservancy’s Vandell Preserve at Cumberland Marsh, a spectacular complex in the Lily Point Marsh along Holt’s Creek on the west side of the Cumberland peninsula. It’s a great area to paddle (launch from Lester Manor), and there’s an ADA-accessible boardwalk for land-bound birders. The Cumberland Marsh is particularly spectacular to explore in late summer, with its wild rice and other marsh plants in bloom, and in the fall as colors develop in its trees.

Turning around just below Cumberland Landing, we entered Cumberland Thoroughfare, which cuts through the base of the Lily Point Marsh and provides access into Holts Creek. Here we encountered another pair of practicing bass anglers who had caught several on- to three-pound bass casting weedless-rigged flukes to shoreline cover. Coming out of the Thoroughfare headed upriver, we found ourselves opposite the 1,600-acre Pamunkey Indian Tribe’s Reservation, a large peninsula shaped like a quarter of a pie that the tribe has inhabited since 1646, fishing, hunting, trapping, and gardening. It is perhaps the oldest inhabited Indian reservation in North America. Marsh and woods rim the reservation’s shore except for the tribe’s well-used landing, which includes its longstanding, sophisticated shad hatchery.

Pamunkey watermen are skillful fishers, with both hook-and-line and the drift nets that their treaty allows them to fish for American shad, river herring (alewives and bluebacks), and other species for subsistence. They have worked closely with DWR and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service fishery scientists for years to restore shad stocks, though both shad and herring stocks remain depressed. Members of the tribe have also participated in research on the Pamunkey’s small (and endangered) but spectacular Atlantic sturgeon stock, including large spawners in the fall. At the turn of the 20th century, during the heydays of the shad, herring, and sturgeon fisheries, a village at Lester Manor played an important role in processing and shipping fish to wider markets.

Just beyond the Pamunkey Reservation on the opposite shore, we approached White House, a quiet spot today but one with deep historic significance. It was the home of the widow Martha Custis when she was courted by, then married George Washington in 1759. It figured as a Union base in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. White House was also the site of the Pamunkey River crossing for the Richmond and York River Railroad. Completed in 1861 between Richmond and West Point, the railroad formed a vital link from Richmond for freight and passengers who transferred to steamboats running to Baltimore and Norfolk. (Lester Manor lies just east of White House on the rail line, which made it the logical stop for shipping Pamunkey fish.)

Above White House, the Pamunkey offers several broad reaches much loved by water-skiers in warm weather, as well as coves and creeks for anglers in all seasons and waterfowlers in cold weather. In addition to bass, the river offers a strong blue catfish fishery, with both 15″-25″ “eaters” and trophy-sized behemoths for release. It also grows yellow (ring) perch in the upper tidal reaches and white (stiffback) perch further down.

As we returned to Lester Manor, a local angler pulled in aboard a big jonboat clearly rigged to take advantage of the Pamunkey’s variety, with an electric trolling motor on the bow for casting to bass and a rack of rod holders across the transom to set lines for cats or panfish. At all seasons, the Pamunkey invites us to explore its wondrous wildlife from Lester Manor.

John Page Williams is a noted writer, angler, educator, naturalist, and conservationist. In more than 40 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Virginia native John Page championed the Bay’s causes and educated countless people about its history and biology.