By John Page Williams

Photos by John Page Williams

The Rappahannock River between Port Royal and Fredericksburg looks pretty quiet most days, but it hasn’t always been so. Over the past 90 years, roadways have taken over nearly all of the region’s commercial and personal traffic, but prior to the 1930s, this water was busy for at least a thousand years.

Recently, two friends and I pondered this contrast as we turned from King George County’s Port Conway Road onto well-named Old Wharf Road, headed for Hopyard Landing. Today, that age-old trail leads through a brand-new housing development, part of the county’s population growth between employment centers in Fredericksburg and in the Navy Surface Warfare Center at Dahlgren.

We realized, however, that we were actually driving through the site of Upper Cuttatawomen, a thriving Chief’s House town mapped by Capt. John Smith during his exploration of the tidal Rappahannock in August 1608. Like many towns of the Native American people living along the Chesapeake’s rivers then, this one lies on the outside of a curve, with a marsh and a wooded swamp on the inside. Capt. Smith noted in his General Historie that the king of Upper Cuttatawomen “used us kindly, and all their people neglected not anything …to bring us to them.”

Smith mapped several satellite villages in the region, on both sides of the river. Just upriver, around today’s Moss Neck, Smith’s crew buried their member Richard Fetherstone, who had died onboard, into the river “with a volley of shot.” He was the only casualty of that summer’s explorations, despite their “ill diet and bad lodging, crowded in so small a barge in so many dangers.”

At Hopyard Landing, we found a single-lane, concrete ramp with a pier on one side and a bulkhead with walkway on the other. The day was windy and cool, with a light chop on the river. As we slid my skiff, First Light, into the river, we talked about what made this curve so attractive to both the Cuttatawomen people and the English colonists who settled here in the late 17th century. With deep water and fast land, it was a natural site for Cuttatawomen agriculture and later for a farm wharf from which local planters could ship tobacco, grain, and lumber out, and manufactured goods in.

We marveled, though, at the skill and patience that ship captains must have had to navigate their vessels of that period up the winding, narrow river, whose wooded banks and strong currents must have made sailing seriously challenging. We were thankful to have a modern, efficient four-stroke outboard happily purring behind us as we ran a short way upriver past wooded shorelines to pay our respects to Richard Fetherstone’s burying ground. Sea level has risen about three feet since then, and enough sediment has collected on the inside of that turn that whatever is left of the crewman’s remains lie today somewhere under the wooded swamp on the King George side.

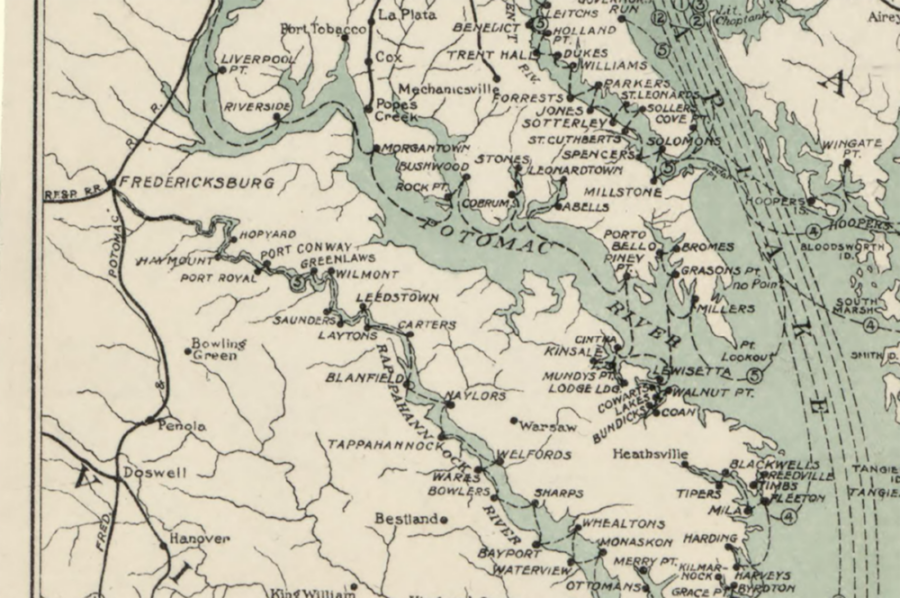

Given the difficulty of sailing, it’s no surprise that when steam power became available early in the 19th century, Virginians began to ply the river with steamboats for both commercial and passenger traffic. In the 19th century, the steamers actually made it easier for local people to visit and do business in Baltimore or Norfolk than to travel overland to Richmond or Washington, D.C. There were 14 stops at wharves along the Rappahannock between Tappahannock and Fredericksburg, including Hopyard and Haymount, just downriver on the Caroline County side.

Steam, and later diesel fuel, allowed tugboats to tow and push barges to carry bulk goods—lumber, sand, and gravel—downriver. Look at this part of the Rappahannock around Hopyard on Google Earth and you’ll see the open pits of former and current sand mines, though today they “ship” the building materials by truck. During the steamboat and tugboat era on the river, though, navigation of the Rappahannock’s meandering channel required considerable skill.

Captains and crews gave colorful names to the most challenging features, each of which demanded specific strategies at different stages of tide and current: Carter Short Turn, Rock Creek Turn, Park Turn, Longrange Turn, Popcastle Turn, Devil’s Woodyard Turn, Moss Neck Bar, Springhill Reach, Hayfield Bar, Hollywood Bend, Castle Ferry Bar, Fox Spring Bend, Snowden Bar, Daingerfield Short Turn, Spottswood Bar, Epson Turn, and Smithfield Bar. It would be great fun to hear the stories behind those names.

Turning downriver, we followed the winding channel, marveling again at the skill of 18th-century ship captains who found ways to sail this narrow fairway. It acted as a wind tunnel; the day’s fresh breeze alternately pushed us along and then sent a chill through our jackets. The topography below Hopyard is dramatic, especially 161-foot-high Talliaferro’s Mount on the Caroline side and steep, wooded Haymount just beyond, with the deep ravine of Mount Creek between. This combination of lookout elevation and ravine with freshwater creek was especially valuable not only for humans—Natives and later, English colonists—but also for birds like bald eagles and migratory waterfowl, and for marsh furbearers like river otters, raccoons, and muskrats.

We turned the corner to get a look at the large Cleve Marsh on the King George side. Like so many of the similar river marshes along the upper tidal Rappahannock, Cleve provides stunning habitat for wintering ducks, geese, and swans.

We worried, though, about the degree to which rising sea level and land subsidence are flooding marshes like this one and far too many others further downriver. The most obvious symptoms are dead trees killed by high water around their roots, but the flooding also changes the mix of marsh plant species upon which wintering waterfowl depend. The long-term effects of vegetation change and corresponding habitat value are still unknown and worrying.

Fishing opportunities in this stretch of the Rappahannock’s tidal fresh section are diverse, especially in spring, when anadromous fish like yellow (ring) perch, white (stiffback) perch, river herring (alewives and bluebacks), shad (American and hickory), and striped bass (rockfish) ascend the river to spawn. Year-round residents include largemouth bass, occasional smallmouths moving downstream from the river above Fredericksburg, northern snakeheads, and blue catfish.

In the section around Hopyard, look for largemouths around fallen trees, especially those with sharp channel drop-offs nearby. These bass will often lie in ambush in quiet water behind an obstruction, waiting for the river’s current to sweep baitfish past. Many anglers favor falling tide for this pattern. Look for snakeheads back in the marsh vegetation. If you catch one of these toothy, invasive fish, handle it carefully but by all means kill it and take it home to eat. You should also report the catch to the Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR).

John Page Williams is a noted writer, angler, educator, naturalist, and conservationist. In more than 40 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Virginia native John Page championed the Bay’s causes and educated countless people about its history and biology.