Oak Toad © Jeff Beane

Today’s Frog Friday spotlight is on a small but very handsome toad—the Oak Toad. The Latin name for this toad is Anaxyrus quercicus, which means “king” or “chief” and “oak leaves.” This “king of the oak leaves” has a dark-colored background with 4 to 5 pairs of spots on its back and a conspicuous stripe, typically white, yellow, or golden, running down its back. The skin has a finely roughened appearance with numerous small bumps (tubercles), many of which are red in color. The bottom of both the front and rear feet also have several red bumps/tubercles.

Oak toad © Steve Roble

During much of the year, Oak Toads are associated with pine or oak savanna habitats in sandy soil. Oak Toads can be found mostly in open, grassy areas of these pine or oak savannas. Unfortunately, much of the preferred habitat of this species is either in decline or significantly altered. Throughout much of its range, Oak Toads are closely associated with longleaf pine ecosystems, which are declining throughout the southeast. In addition to the loss of longleaf pine habitat, natural stands of pine and pine-oak are also declining primarily because of development, lack of fire, and the conversion of these stands to commercial loblolly pine monocultures.

Oak Toads breed from April to September in shallow pools, almost always following a heavy rain event. The call sounds much like the peeping of newly hatched chicks and up close can be ear-piercing. Females lay up to 500 eggs in small bars or strands of 2–8 eggs each. Eggs can hatch in one day with metamorphosis occurring in 30 to 60 days.

Listen to the Call of the Oak Toad:

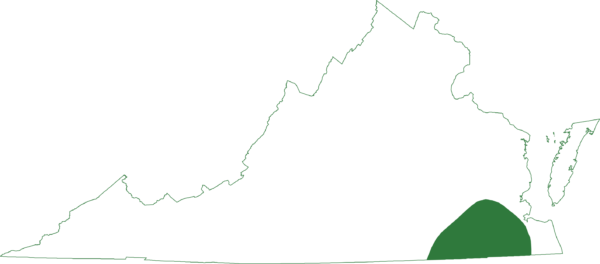

Oak toad map

At only 0.75 to 1.3 inches in length, the Oak Toad is considered to be the smallest toad in North America. In Virginia, this species is known from only a few locations in the southern coastal plain. The Oak Toad is considered a Tier II species in the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan. Tier II designation means that population numbers are very small and they only occur in a few locations. Conservation efforts for this species should focus on the unique savanna habitats that are important for the continued viability of populations in Virginia. Visit this website for more information on the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan.