A royal tern adult flies above Ft. Wool carrying a fish (Clupeid sp.). Photo credit: Aileen Devlin/Virginia Seagrant

By Meagan Thomas/DWR

Well seabird supporters, you know what they say – all good things must come to an end and therefore this post will be the last in our blog series covering the 2021 Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel nesting season. It’s been a whirlwind of a summer for us here at DWR, and we hope you’ve not only enjoyed the series, but also gained some additional insight into the captivating life of a seabird!

Now empty barges in the embayment of the HRBT site. Photo credit: David Norris/DWR

Last month’s post contained the news that there were still a handful of black skimmer, common tern, and royal tern chicks on Ft. Wool and the barges—a product of late nesting or re-nesting attempts. While we’re thrilled to have as much recruitment into the larger population as we can get, the projected fledge window for the common tern and skimmer chicks atop the barges was dangerously close to exceeding the end of our barge contract. Fortunately, DWR staff were able to visit the site earlier this week to check on the status of these juveniles. While a few royal terns remained on Ft. Wool, the black skimmer and common tern chicks appear to have moved on to new horizons, leaving the barges now eerily quiet. And thus, with hurricane season bearing down upon us, the mad dash begins to get the barges pulled out of the embayment as soon as possible. With any luck and decent weather, this will be accomplished by the end of next week.

So what’s next for this new generation of seabirds? Simply put, it’s all about migration. Post-fledging seabird dispersal often includes what biologists refer to as a reverse migration, where a bird begins its journey by first heading in the opposite direction of where it ultimately overwinters. In the case of many seabird species, the adults and juveniles will travel to locations as far north as New Brunswick and Nova Scotia before shifting gears and heading back to their southern wintering grounds. This year alone we’ve already received numerous observations of royal tern adults and juveniles from Maryland, all the way to New York. But, despite this initial venture north, the birds will eventually reverse course and head south to their final wintering destinations including southern portions of the United States, the Caribbean, or South America. Check out the below photos containing a juvenile royal tern which was banded in 2020 at the HRBT site and seen in Honduras this August!

A juvenile royal tern with a field readable band (banded in 2020 on Ft. Wool) can be seen amongst a flock of sandwich and royal royal terns near the mouth of the Cangrejal River in Honduras. Photo credit: Francisco Dubon

A closer look at the banded royal tern chick that was spotted in August of 2021 near the mouth of the Cangrejal River in Honduras. Photo credit: Francisco Dubon

Throughout migration and even after arrival to their wintering sites, adults will continue to feed and tend to their recently-fledged offspring. If the juveniles survive the strenuous migration journey, they will typically remain there for at least one or two more summers before migrating north as breeding adults. However, a bird’s first migration back to the nesting grounds doesn’t always equate to that bird’s first nesting season. In fact, last year we saw the return of several royal terns which were banded in 2018 at South Island utilizing the newly provided habitat at Ft. Wool, but despite this inclusion within the larger colony, none of these individuals were confirmed to be breeding.

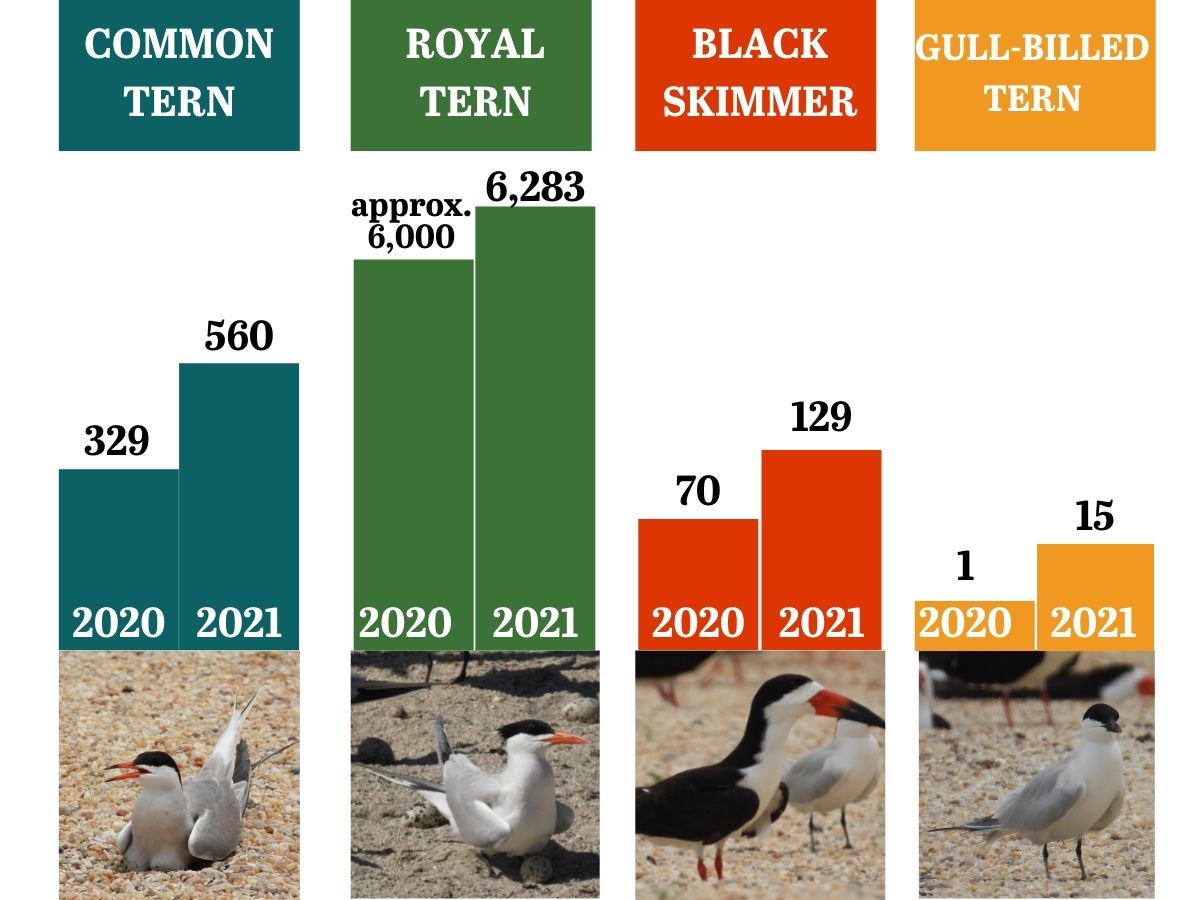

With that in mind, we are thrilled to report that 2021 was an incredibly significant year as it was the first time we’ve seen birds (i.e., royal terns, common terns, and black skimmers) which were banded as chicks on South Island not only make the journey back, but also nest on either Ft. Wool or the barges. Additionally, based on Virginia Tech’s early investigations of the data, 2021 appears to have supported as many, if not even more nests than what we documented during the 2020 pilot year.

Preliminary investigations of minimum nest counts (note this is different from total nest counts) indicate that 2021 is shaping up to have had more nesting activity relative to what was documented in 2020, however additional data investigations are still being conducted to confirm this. Photo credits: Meagan Thomas/DWR

One thing many of our readers may not realize is that the study of this population will ultimately have a substantial impact not only on our understanding of this particular colony, but of these species throughout their respective ranges. Ecologists know shockingly little about the natural history of seabirds—things like migratory patterns, nest site selection, survival rates, age at first breeding and other demographic parameters are all in dire need of additional study. For example, while it is generally assumed amongst researchers that royal tern adults breed annually as opposed to alternating years, the limited amount of banding data we have makes even that simple assumption difficult to confirm.

Our banding efforts of birds within this colony are the first to include field-readable bands, the importance of which cannot be overstated as these easy-to-read bands have the power to yield impressive numbers of reported re-sights throughout the range of each species. Since 2018 a total of 13,377 birds have been banded on South Island, Ft. Wool and the barges, of which 9,605 (72%) have received these uniquely coded field readable bands. So if you catch a glimpse of a banded seabird, don’t forget to report your observation to us via our online reporting form. After all, it is only by way of these reports that we will ultimately be able to fill in those major gaps in our understanding of these species’ life histories.

A royal tern chick stands on the Ft. Wool parade ground. Photo credit: Meagan Thomas

And what about us here at DWR? You may be left wondering what our plans are for the future of the HRBT seabirds. Well, for our staff, the work to support this colony never ends whether the birds are here or not. The barges will be back next year to provide the colony with suitable habitat in preparation for next year’s nesting season, but like the birds, we are keeping an eye to the future and planning our own migration to a more permanent management solution. After all, Fort Wool and the barges were never intended to be the final destination for this colony. It was an idea that was put into motion within just a few short weeks in an attempt to come up with some type of suitable nesting habitat once South Island was no longer safe for the colony. And while we’ve seen tremendous success with the site, it certainly isn’t a sustainable or feasible long-term option.

Ultimately, we hope to provide the birds with at least one dredge-spoil island that’s designed just for them, providing the colony with desperately needed security for decades to come. As an agency, we are navigating that process with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in an effort to make this vision a reality within the next three to five years. There is no doubt that the endeavor is fraught with challenges, but if we’re able to pull it off, we may be able to provide the birds with their island as soon as 2024—just in time for the return of this year’s fledglings.

Thanks again to our many dedicated followers that have tuned into our HRBT blog! It has been an absolute pleasure to provide you with a bird’s eye view of all that’s been going on at Ft. Wool and the barges this season. With that in mind, we’d really love to thank everyone who completed the short survey about the blog, your feedback will help us determine what HRBT-related information you would like to see more of in the future!

Terns and laughing gulls lounging on the Ft. Wool Rip Rap. Photo by Aileen Devlin/Virginia Seagrant