By Molly Kirk/DWR

Photos by Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center

You might not think of sea turtles when you think of the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), but the agency is responsible for those species as well! The loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) is the most abundant species of sea turtle that nests in the United States, but the Northwest Atlantic population, which nests primarily along the Atlantic coast of Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina and along the Florida and Alabama coasts in the Gulf of Mexico, is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, as of 1978.

The loggerhead—named for the species’ large head and powerful jaw muscles that enable them to feed on hard-shelled prey—can mature to a shell size of between 3 to 3 ½ feet and can weigh between 250 and 400 pounds as adults. Like all sea turtles, loggerheads must come to the surface to breathe air. Adult females lay their eggs on beaches, often returning to a beach near where they hatched decades earlier.

A loggerhead turtle returning to the ocean after laying eggs on the beach.

Threats to loggerhead populations include unintended capture (bycatch) in fishing gear, loss and degradation of nesting habitat, vessel strikes, ocean pollution and debris, and a warming climate.

“Virginia is recognized as the northernmost consistent nesting area for loggerhead turtles,” said Dr. Susan Barco, DWR subject matter expert on protected marine species. “We get a relatively low number of nests, but the animals that nest in Virginia, the hatchlings, may be contributing more and more in the future to the population growth because there’s liable to be some movement northward, as climate change and sea level rise continue.”

Interestingly, loggerhead turtle hatchlings have a temperature-determined sex ratio—the warmer the nest, the more likely the hatchlings are to be female. As average temperatures warm, there’s a worry that the population will skew too far to producing females. Barco noted that southern nesting populations are starting to nest earlier, but also that “the northern areas may become more and more important for contributing males to the population,” she said. “We certainly have some prime uninhabited, unpopulated areas on barrier islands that could be utilized for nesting.”

A loggerhead turtle hatchling on its way into the ocean.

After they hatch, juvenile loggerhead turtles spend 10 to 30 years in the open ocean, but then return to closer to shore as large juveniles, and the Virginia coast is “a very important juvenile foraging area,” Barco said. “There have also been tagging studies that have shown that after they nest, mate and breed, adults from Florida, South Carolina, Georgia will move into this area to forage. We see them in inland waters, we see them 40 or 50 miles offshore, but they’re primarily feeding on crustaceans, mollusks, and horseshoe crabs, and a lot of that prey is pretty readily available in the Chesapeake Bay area. It’s a very productive area for forage compared to some of the areas south of here.”

In the Virginia area, the primary protections afforded to the loggerhead turtles by the ESA are management of the Virginia Stranding Response Program, part of the National Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network, and monitoring for and protection of sea turtle nests. DWR is responsible for these programs but works intensively with conservation partners such as The Nature Conservancy, Back Bay, Eastern Shore and Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuges, ocean-facing military bases and the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center to implement them.

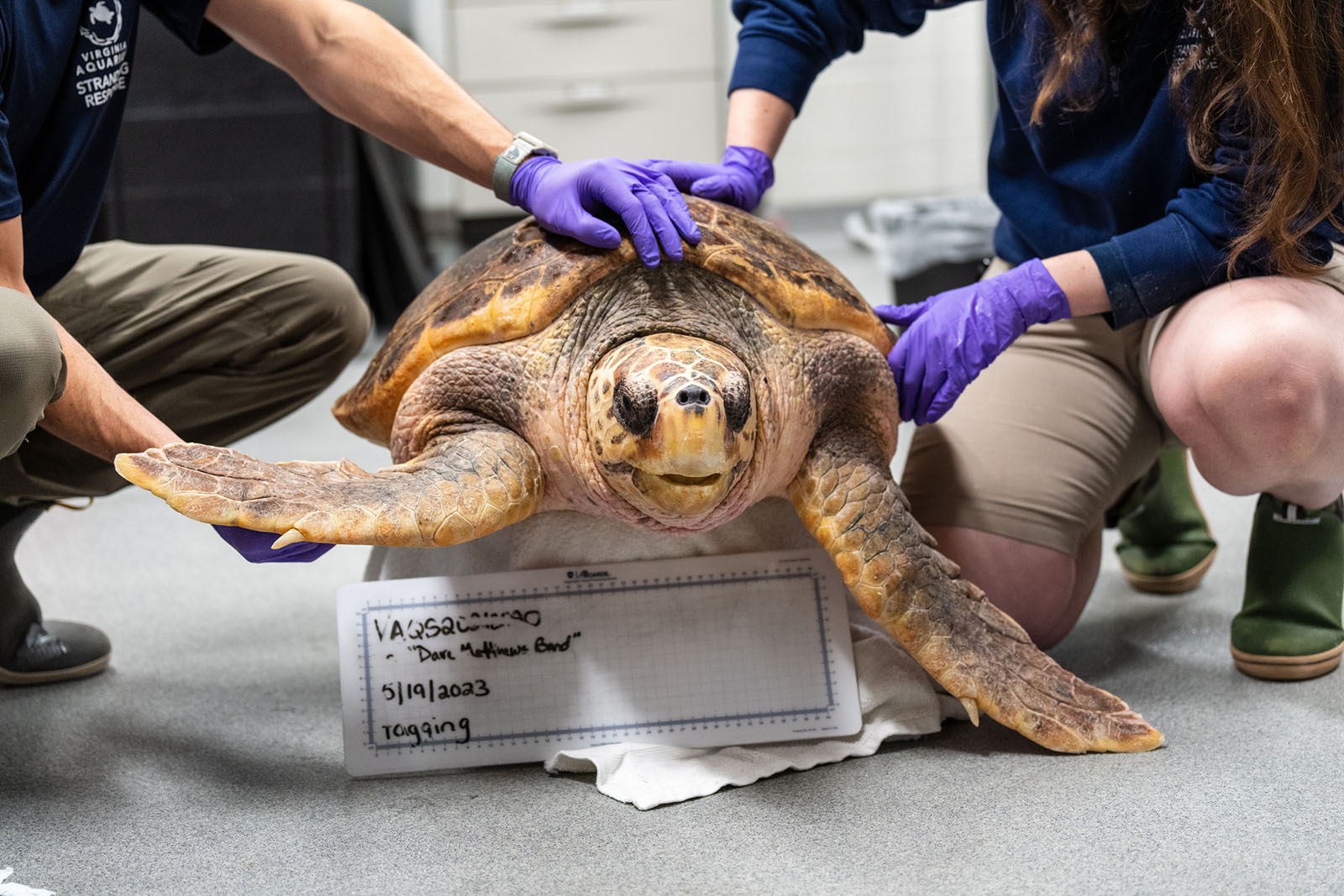

The Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center in Virginia Beach manages the Commonwealth’s sea turtle stranding response program, which not only studies sea turtles that strand, but also responds to live stranding and entanglement reports by rescuing, rehabilitating, and releasing turtles that have been trapped in fishing gear, caught by anglers, cold-stunned or injured by vessels. Funding from ESA grants to DWR through the Recovery Grants to States program as well as other programs have helped support the Virginia Stranding Response Network.

A loggerhead turtle that was recovered by the Virginia Stranding Response Network at the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center.

Management of sea turtle nest monitoring efforts falls to the owner of the beaches where nesting occurs—wildlife refuges manage their beaches, the City of Virginia Beach manages nest monitoring through the Virginia Aquarium, the military bases manage the nest monitoring on those installations, and [DWR Coastal Terrestrial Biologist Ruth Boettcher] and colleagues at The Nature Conservancy monitor nesting on the barrier islands.

A loggerhead turtle navigates back to the ocean among beachgoers.

Further ESA assistance for loggerheads came through changes in design of fishing gear to prevent bycatch, especially the use of Turtle Exclusion Devices on shrimp trawl nets and crab pots. “In Virginia, there was a big problem in the late ‘90s and early 2000s with pound-net captures,” said Barco. Pound nets, a type of fish trap staked out in the water, at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay were catching worrying numbers of turtles. “The Virginia Aquarium and Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) worked with the National Marine Fisheries Service, local pound net fishermen, and a contractor to design and test an alternative leader design for pound nets that was later adopted by both the federal agencies and the state to reduce turtle bycatch. That same design was later introduced for bottlenose dolphin bycatch as well. And that was a fisherman’s design. One of the pound-netters came up with a design, there was a pretty rigorous testing process, and then it was adapted once it was successful.

“The Endangered Species Act has really provided tools for conservation managers to address issues that we can identify,” said Barco. “For animals where there are there are very specific causes of mortality and serious injury, the ESA provides good tools for dealing with issues like hardening of beaches, beach lighting, and fishery bycatch, those sorts of things. If we can identify a source of the problem, the ESA is really good at providing tools and legislation and regulation to help with those things.”

Barco noted that two factors make it difficult to know exactly how the ESA protections have impacted loggerhead populations. First, population surveys of loggerheads are difficult, as they’re a migratory species with a massive area of range. And, it’s difficult to find, see, and count marine animals. Second, loggerheads’ life span makes impacts of conservation actions difficult to measure.

“These turtles don’t mature and start nesting until they’re 30-plus years old,” notes Barco. “Conservation measures that started when the ESA passed in the ‘70s would just now be showing an effect, and of course it took a decade or more before truly meaningful conservation measures were able to be in place after the ESA passed. Loggerhead turtles, like other long-lived animals, are generational species to follow. It’s very hard for one scientist, during his or her career, to live long enough to see these changes. I think we are all expecting that loggerheads and green turtles are both doing relatively well, from what we understand. But they’re a very tough species to study.”