By Dr. Leonard Lee Rue for Whitetail Times

Photos by Dr. Leonard Lee Rue

The hilltop farm I was raised on during the Great Depression had 106 acres with only 56 acres actually being crop land, while about half of the remaining land was in pasture and the rest in orchard and woodland. We milked about 12 cows and couldn’t expand our herd because we couldn’t raise enough food to feed them. So, it was then that I learned about the “carrying capacity” of land at a very early age. You can’t raise more of anything than you have food to feed it, and that is the basis of deer management.

People either love deer or hate them, according to whom you talk. Hunters want to see a deer behind every tree, in fact over the past couple of decades there was a deer behind most every tree. Today, there aren’t that many trees, and a large part of the problem is that the over-abundance of deer is preventing reforestation over much of the deer’s range. Biologists, long ago, calculated that a good range could be self-sustaining at no more than 20 deer to the square mile. Maintained at that number, the deer and their available food supply would be in balance with both benefiting. Game laws in many states allowed the deer populations to skyrocket. In my home state of New Jersey, we had a heckuva job convincing both hunters and the general public that we needed to change the laws to allow does to be shot for the first time. Deer can reproduce themselves at an annual rate of 35 to 40 percent, which means that they should be shot at about that same rate.

It is absolutely true that an overpopulation of deer can literally stop any forest regeneration by eating the seedlings as fast as they sprout but by eating the nuts, particularly the acorns, there are fewer seedlings to eat. I fully agree with that statement or I wouldn’t have written it.

In doing some research for a book that I was writing on deer behavior, I investigated a deer’s capacity to eat acorns. I realize that their favorite acorns are those of the white oak, but that is always a sporadic crop, with the trees producing a good crop every three to four years. What they mainly eat are the acorns of the red or black oaks.

Gathering a bunch of the acorns from a red oak, I weighed them and found that they averaged six acorns to the ounce or 96 acorns to the pound. During most of the year, except December, January and February, a deer eats about eight pounds of vegetation per 100 pounds of body weight per day. So, a 150-pound deer would eat 12 pounds of food, and if it was eating acorns that would be approximately 1,152 acorns per day.

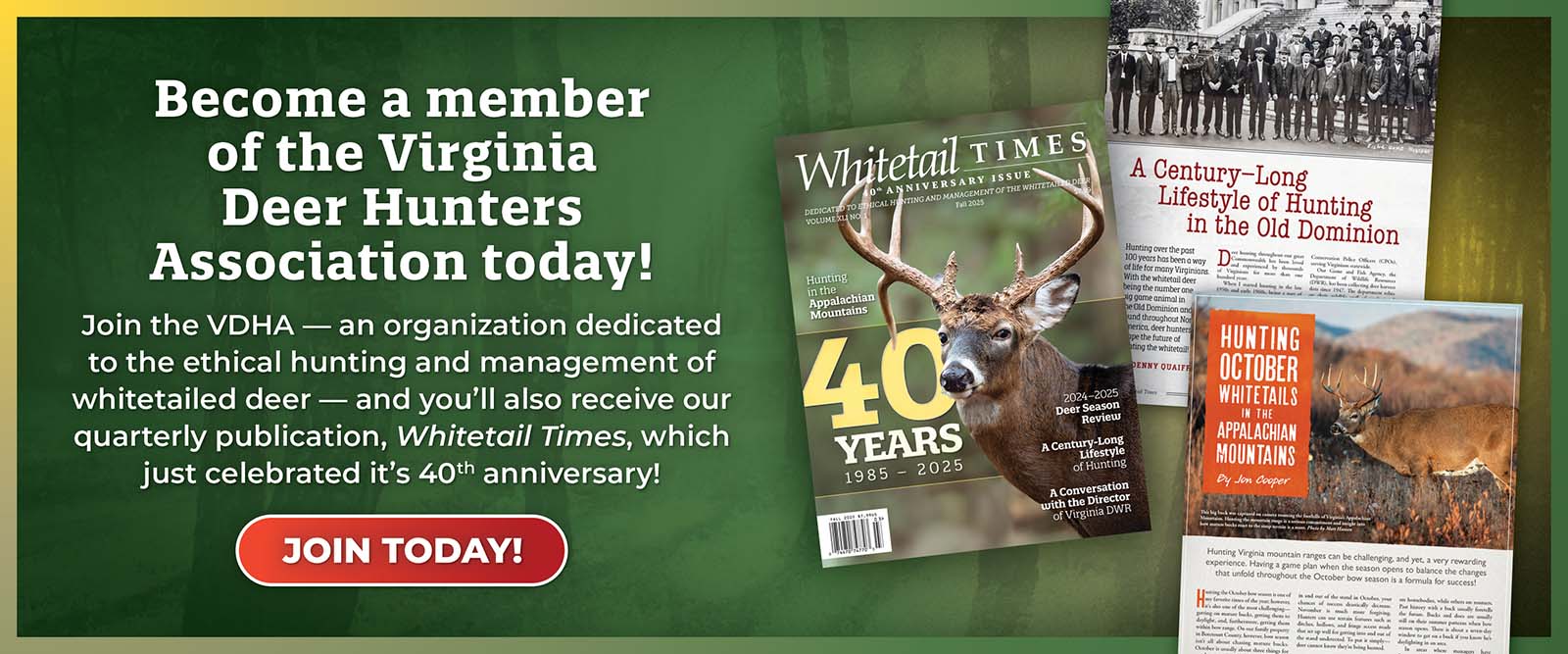

One of the white-tailed deer’s prime food sources in the fall is acorns. Their favorite is those of the white oak, as pictured here, with these trees producing a good crop every three to four years. When rich acorns start to cover the forest floor, deer movement will be far less than years when acorn crops fail, and hunter success rates are often challenged.

However, deer innately know what we have to be taught, that it is important to eat a more balanced diet and if it is available, deer always eat other vegetation along with the acorns. Not being able to confirm the amount of other vegetation, I have arbitrarily assigned it a figure of 20 percent, which would then limit their acorn intake to about 920 acorns per day. Research done in Pennsylvania found that an oak forest is capable of producing about 550 pounds of acorns to the acre in good years. Not every year is a good year. In fact, in parts of Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 2008, there were no acorns at all due to the gypsy moth caterpillars defoliating the trees.

One of the greatest success stories in conservation is the return of the wild turkey, with Virginia being one of the most successful states. From a mere handful of turkeys, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) estimates there were 180,000 turkeys in the state. Those thousands of turkeys love acorns too; it is one of their major foods. An adult turkey’s crop holds about one cup of food or about what a person could hold in one cupped hand. According to the size of your hand, that would be about 18 to 20 acorns or one pound of acorns for every five turkeys or about 720,000 acorns a day for the state’s flock.

Folks don’t hunt gray squirrels as much as they use to, and the gray squirrel’s main job in the fall is to gather nuts to be used as food to tide them over the winter. Squirrels are early risers, and except for taking a break in the middle of the day, they gather acorns—hundreds of acorns—over most of the day and do what is known as “scatter-hoarding.” The white oak acorns are eaten at once because they sprout almost as soon as they fall and rapidly lose nutritious value after sprouting. The squirrels gather the nuts one at a time and then bury them beneath the leaf mold to be dug up later to be eaten. It is true that most of our hardwood nut forests are the result of those nuts being buried and not retrieved by the squirrels.

The chipmunks too, gather vast numbers of acorns. Usually, they only carry two or three acorns off at a time, but they have been documented carrying five and they average eight hours of work per day. Chipmunks are classified as hibernators, and they do retire from sight about the first of December, when the weather turns cold. They do not sleep throughout the winter as does the woodchuck, but wake up frequently and feed upon the food they have cached. Apparently, their appestat is broken because chipmunks always store more food than they could possibly eat. They store their acorns underground and usually sleep on top of their hoard.

And, let’s not forget the black bears that scarf down thousands of acorns per day per bear. Bears are not true hibernators because their body temperature remains high, whereas true hibernators have their temperatures drop to just above the freezing point. The bears are subject to mandatory lipogenesis, as are the deer, and they have to layer fat upon their bodies in order to survive the winter. A bear killed in Wisconsin had a layer of fat on its body that was five inches thick over its back with the fat weighing a total of 212 pounds. The Pennsylvania Game Commission estimates their black bear population at about 18,000 animals. The tons of acorns those bears eat each and every day, while they are available, is just mind-boggling.

In areas where Lyme disease is prevalent, authorities have tried to drastically reduce the deer population because they do carry the deer tick, which is the main vector spreading the disease. Research has shown that the white-footed mice are more likely to spread the disease than the deer. Over 40 species of birds are documented to also be host to the ticks, but they are called deer ticks and it is the deer that get the blame. While it is true that the overabundance of deer is the main factor in preventing the regeneration of our forests, I think it should be known that they have lots of help but, again, the deer get the blame.

Dr. Leonard Lee Rue III wrote a column for Whitetail Times until his passing in November 2022, and his wife, Uschi, granted Whitetail Times permission to publish his remaining lifework.

©Virginia Deer Hunters Association. For attribution information and reprint rights, contact Denny Quaiff, Executive Director, VDHA.