By Stephen Living

Photos by Stephen Living

Looking out my office window, I could see a flurry of activity around one the holly trees in my back yard. A steady flow of birds flew in and out of the tree and hopped amongst the branches plucking berries. I wandered outside to stretch my legs and enjoy the show. My tree is an American holly (Ilex opaca). The leathery evergreen leaves are broadly toothed and spiny, and this one is covered in bright red berries.

This tree has smooth, gray bark and typically grows from 15 to 40 feet high. It is a common component of forests through much of the Eastern United States and across most of Virginia. It will grow under a variety of conditions from full sun to shade. Shade-grown trees are likely to be shorter and with relatively fewer leaves compared to those that grow in the sun. Trees grown in full sun also tend to produce more fruit.

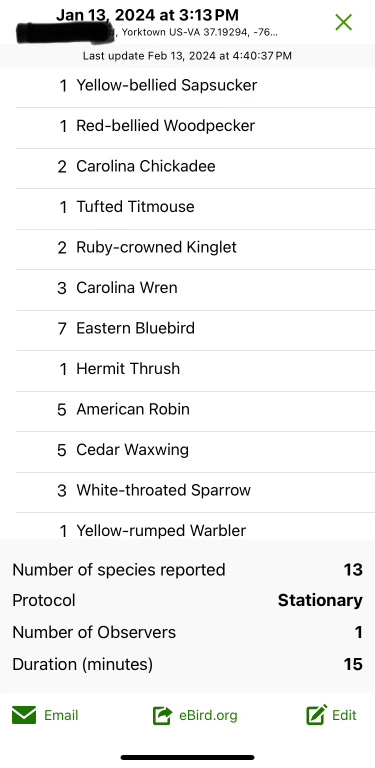

These fruits are an important part of the diet of many winter birds. Cedar waxwings, American robins, eastern bluebirds and hermit thrushes are commonly found in holly trees during the winter, and I quickly heard and saw all of these species. Many other birds will dine on the berries or search for insects and invertebrates wintering amongst the branches and evergreen leaves. As an evergreen, the American holly provides valuable winter cover. Wild mammals like deer and squirrel will also eat the fruit or even nibble on the spiny leaves. (Please note that all holly berries are considered mildly toxic to humans and dogs). In a short 15 minutes I had 13 species of birds in and around this single tree.

Holly berries provide food for a variety of wildlife species.

Great wildlife habitat in the form of an American holly tree results in 13 bird species spotted in one day!

Hollies (trees and shrubs in the genus Ilex) have male and female flowers on separate plants. This means that only female plants will bear fruit (assuming there are male plants nearby to help pollinate them). If you’re planning on adding one to your landscape, you will need a male American holly somewhere close by to pollinate these flowers and grow fruit. Take a look around—nearby wild plants may do this for you. American holly is a great pollinator plant with small white flowers typically appearing from late April through early June. These are a magnet for native insects, which in turn provide food for birds and other wildlife.

About 30 feet away from all of this bird activity in my yard stood another holly. This one is shorter, with dark green, glossy leaves with a single pointy spine. Although covered in bunches of bright red berries, it attracts no interest from the flock of hungry birds nearby. Not a single bird eats a berry or so much as lands in the holly as I watch.

This isn’t surprising. In the years I’ve watched these trees, it is rare to see a bird try these fruits, and generally only once the American holly has been picked over. This holly is a variety of Chinese holly (Ilex cornuta).

Chinese holly on the left and American holly on the right.

While popular as a landscape plant, it just doesn’t offer the same habitat benefits as the native tree. Native plants generally do a better job providing habitat because our wildlife species are adapted to use them. Native plants are the basic building blocks of healthy food webs for wildlife. More native plants equals more birds and more bees!

Stephen Living, the DWR habitat education coordinator, is a biologist and naturalist with a lifelong love of wildlife and nature that began in the woods and streams of his childhood.