By Brogan Holcombe, Katie Martin/DWR, and Marcella Kelly for Whitetail Times

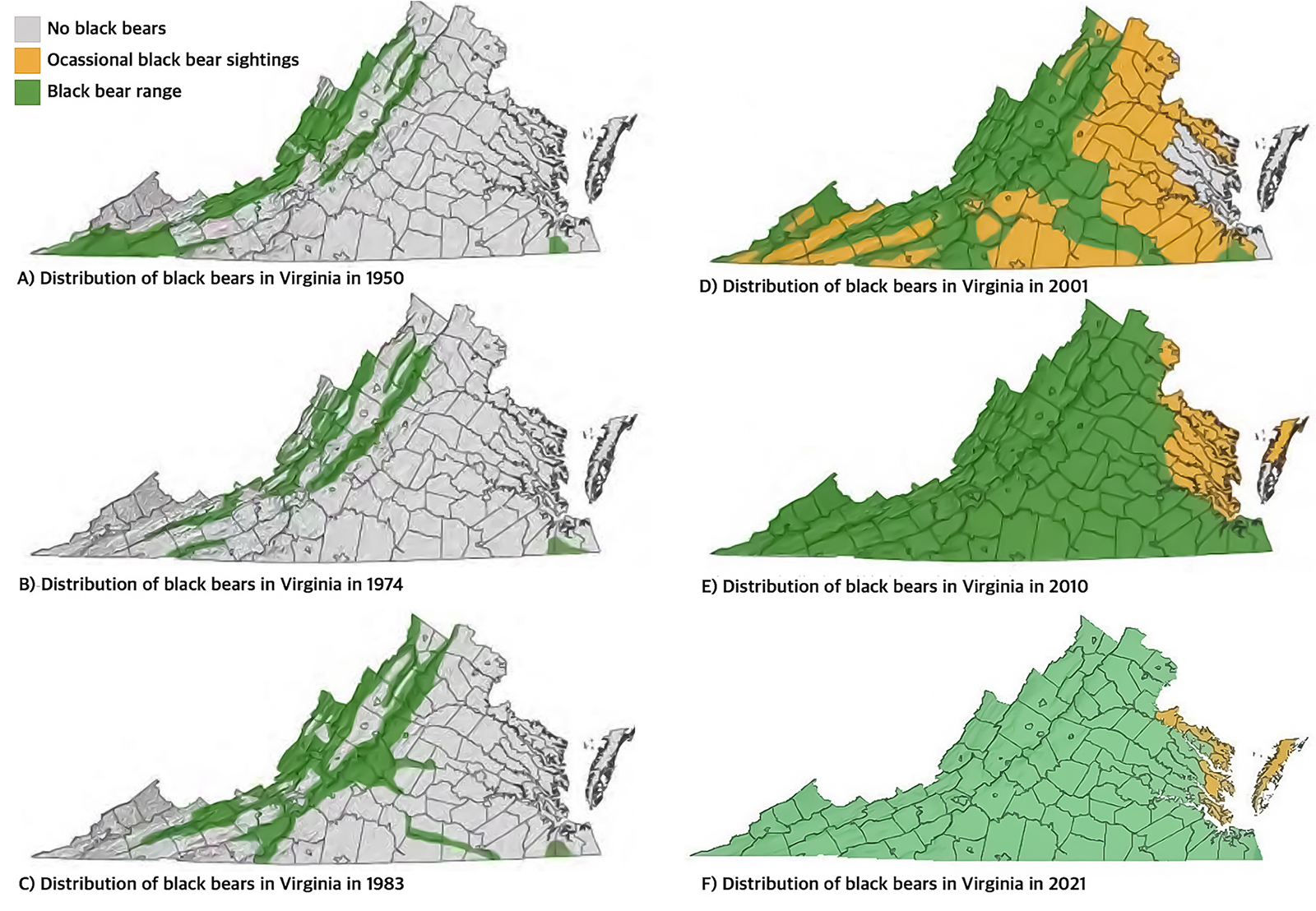

Black bears are currently found across Virginia, largely due to the conservation efforts by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR). Following mass agricultural expansion and deforestation in the late 1800s and early 1900s, black bear populations were low across most of Virginia. DWR and the United States Forest Service (USFS) worked to rebuild wildlife habitat in the state, leading to black bears being listed as a game species in the 1930-31 season. With harvest regulations and habitat restoration efforts in the decades following this, black bears began to stabilize in certain areas and expand to other areas of the state. The maps below show the expansion of bears across Virginia. Presently, black bears are regularly found in almost all areas of Virginia, except for the far eastern counties and the Virginia eastern shore.

Distribution of American black bears within Virginia. These maps are adapted from Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ (DWR) 2023-2032 Black Bear Management Plan.

Using Video Camera Collars to Study Black Bear Foraging

White-tailed deer and black bears co-habitate in much of Virginia, and white-tailed deer are known to be a component of black bear diets. However, the extent of white-tailed deer consumption can vary among individual bears. While working with DWR’s Deer-Bear-Turkey Biologist, Katie Martin, we formed research questions centered around wildlife management and the potential impact of bears on white-tailed deer in Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains. We outfitted black bears in 2018 and 2019 with video camera collars as part of the Virginia Appalachian Carnivore Study (VACS) in Bath County, Virginia.

VACS was initiated with DWR and Virginia Tech’s Department of Fish & Wildlife Conservation in 2016 to better understand the carnivores on the landscape (black bears, bobcats, and coyotes) and their potential impact on declining deer populations in the area. This project occurred simultaneously with the Virginia Appalachian Deer Study, also conducted by the Fish & Wildlife Department at Virginia Tech. This study allowed a better understanding of white-tailed deer behaviors and timing of fawning, and provided demographic information on the white-tailed deer population status in the area.

Collectively, we had 15 black bears (eight males, seven females) that collected between nine and 21 seconds of video every 20 to 60 minutes from May to December, resulting in up to 17 hours of video data per black bear. This resulted in a wealth of GPS points paired with known behavioral observations via camera collars for known foraging and non-foraging events, giving our team unique insight into the consumption events of white-tailed deer by black bears. These video cameras hung below a bear’s chin (Figure 2), and after the team cut chin hairs short, provided clear video clips on a rotating time schedule. Cameras were set at high resolution (1080p resolution) and wide-angle view to document foraging activity and facilitate the search for evidence of fawn and adult deer predation and/or scavenging by black bears. This resulted in a “bear’s-eye view” that provided unique insight into black bear foraging and behavioral ecology across the landscape.

Black Bears’ Diet Composition in Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains

In total, we watched 135 hours of video data and recorded every food item black bears consumed to assemble the complete black bear diet and document how it changed seasonally. We expected to see higher levels of predation by black bears as they emerged from hibernation in the late spring compared to other seasons, as bears may target less mobile young fawns or simply find them opportunistically while foraging. The deer study in Bath County estimated that peak fawning occurred by June 17, with the earliest fawns dropping on June 6 and the last on July 11 (Clevinger 2022).

We categorized seasons based on visual confirmations via camera collar data during the time black bears were collared (May 30 to December 15). We defined spring starting with the earliest camera collar start date (May 30) and went to June 21, which coincided with the vegetation of the summer months coming into season on the videos and is after the peak fawning date in the area. Summer began June 22 and went to August 31, because the first signs of hard mast started to appear in the last week of August. Fall began September 1 and ran until November 30, as this is when the black bears began to have a decrease in activity on the camera collars. Winter was from December 1 to December 15, which is when the camera collars were programmed to stop recording videos.

Collectively, we found that the majority of the black bear’s diet was fruit and seeds (65.9%), followed by leafy matter (12.5%), insects (7.6%), acorns and nuts (6.2%), white-tailed deer (2.5%), human foods (2.1%), fungus species (1.9%), unidentifiable food items (1.0%), and other animal species (0.3%). While white-tailed deer only comprised 2.5% of the black bear’s total diet, we did document seasonal trends in deer consumption. As expected, we found higher levels of deer consumption in the spring diet (12.5%) compared to summer (1.2%) and fall (0.7%).

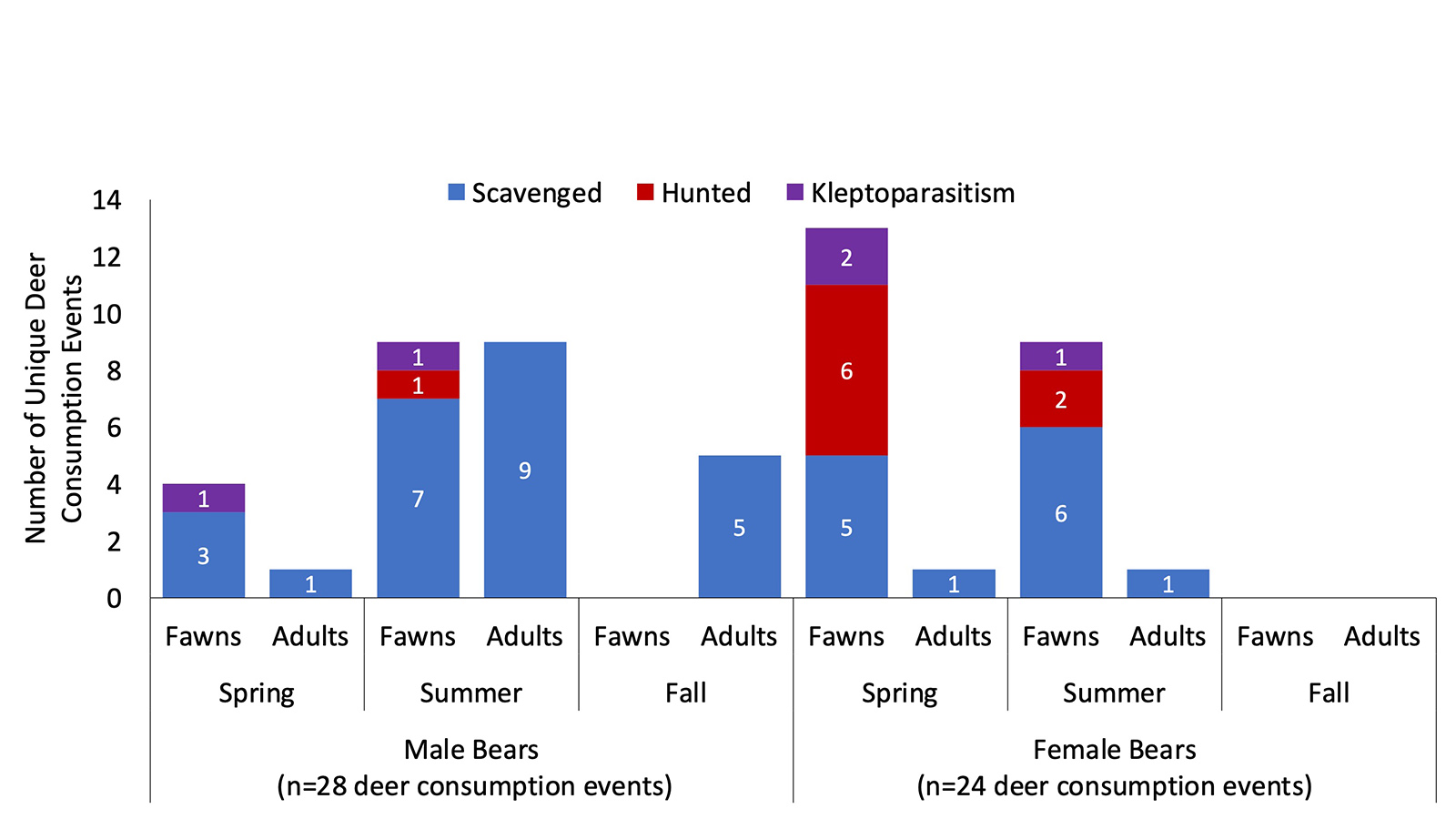

We also found that all or part of 52 unique white-tailed deer were consumed by 15 black bears in 2018 and 2019. It should be noted that in 2018, cameras were mostly operational only in the late spring and early summer, while in 2019, cameras were operational into the fall. Of these 52 unique white-tailed deer encounters, 28 were consumed by male bears, and 24 were consumed by female bears (Figure 3). Seasonally, there were all or a part of 17 unique fawns consumed in the spring. Of these 17 fawns, male bears consumed four, with three of those scavenged and one scavenged from a bobcat cache (i.e., kleptoparasitism or prey-stealing). Female bears consumed more fawns in spring than males at 13 of the 17 unique fawns, five of which were likely hunted and one confirmed as hunted on video, five scavenged, and two scavenged by kleptoparasitism from bobcat caches. Only two adult white-tailed deer were consumed in the spring, with one scavenged by a male bear and one scavenged from roadkill by a female bear.

This graph shows the number of consumption events of white-tailed deer, separated by whether they were scavenged, hunted, or stolen (kleptoparasitism) from a bobcat cache, out of the 52 total observed deer consumption events across 15 bears in Bath County, Virginia, in 2018 and 2019.

In summer, all or a part of 18 fawns were consumed (nine by male bears and nine by female bears). Of the nine fawns consumed by male bears, seven were scavenged, one confirmed as kleptoparasitism, and one confirmed as hunted. Of the nine fawns consumed by female bears, six were scavenged (including one shared with a male bear during a mating series), two were likely hunted, and one was confirmed as kleptoparasitism. There were all or part of 10 adult white-tailed deer scavenged in summer, nine by male bears and one by a female bear.

In the fall, no fawns were consumed, and only all or a part of five adult deer were scavenged by male black bears in 2019. Female black bears were not observed consuming white-tailed deer in the fall.

There was considerable variation in the number of different deer that each bear consumed (0-10 unique deer per bear). We observed 13 of the 15 bears consuming white-tailed deer at some point during the study. For males, seven out of eight bears consumed all or part of one to 10 unique deer, with the average being 3.5 deer per male bear, and one male bear did not consume any deer. For females, six out of seven consumed all or part of one to nine unique deer, with the average being 3.4 deer per female bear, and one female bear did not consume any deer.

For fawn consumption events only, 10 out of the 15 bears consumed fawns. For males, we found that only half (four out of eight male bears) consumed fawns, with those bears consuming all or part of between one to five fawns each, averaging 1.63 fawns per male bear. For females, six of seven consumed all or part of between one to nine fawns, averaging nearly double the males at 3.14 fawns per female bear.

Takeaways From Results

Our study found that overall, both male and female black bears consumed similar numbers of white-tailed deer. Interestingly, scavenging (including prey-stealing) was the most common method of acquiring white-tailed deer for consumption (83.0% of the 52 deer), with the majority (73.6%) of these events scavenged from other kills, natural death, or roadkill events, and a small amount (9.4%), from stealing from bobcat caches.

We found that black bears did hunt deer but at a much lower rate (17.0%) than scavenging. All hunting events observed were on fawns. Female bears had the majority of the hunting events (88.9%, eight out of nine hunting events by both sexes combined), with six being in the spring and two being in the summer. Male bears only had one hunting event (11.1% of hunting events) in the summer.

“Bear’s-eye view” of a male bear chewing on a set of antlers from a whitetail buck in the fall of 2019 in Bath County, Virginia. This camera study captured new data of the black bear and white-tailed deer in their natural habitat.

We also recorded 12 consumption events of bones or antlers of adult white-tailed deer, which has not been commonly documented in wild black bears. While camera collars provided great insight into the methods of acquiring white-tailed deer, we also used GPS points collected while each video was taken to determine what landscape features might drive white-tailed deer predation by black bears. We found black bears more commonly consumed white-tailed deer further away from people and human settlements in the county. Consumption events also occurred closer to forests and croplands. Furthermore, we found that as the temperatures warmed in spring and beginning of summer, bears were more likely to exhibit longer feeding times, which could result from larger fawns acquired by scavenging and consuming larger, scavenged adult white-tailed deer.

While black bears consume white-tailed deer, particularly in spring and early summer, they are not the sole impact on these populations. Previous research from VACS (Alonso, 2024) has shown that bobcats and coyotes also consume white-tailed deer, indicating that complex predator-prey dynamics, in addition to changing landscapes, likely impact deer populations across the ecosystem. A key finding from the Virginia Appalachian Deer Study showed that fawn predation and consumption by black bears, bobcats, and coyotes in Bath County were not a limiting factor for deer population growth within the county (Clevinger, 2024).

Additionally, this ecosystem has experienced substantial changes in habitat, including general mesophication (increasingly wet conditions supporting moisture-loving plants/trees), and now contains large swathes of the mature forest not generally supportive of white-tailed deer habitat preferences across the landscape. Thus, the interplay between predation and recent habitat changes both impact white-tailed deer populations in the Appalachian Mountains.

Brogan Holcombe is a master’s student in the Fish & Wildlife Conservation Department at Virginia Tech, studying American black bear behavior and foraging ecology.

©Virginia Deer Hunters Association. For attribution information and reprint rights, contact Denny Quaiff, Executive Director, VDHA.