By Justin Folks/DWR

Photos by Lynda Richardson/DWR

“When’s the rut this year?”

The temps are dropping, the leaves are falling, and bucks are on the move. There’s hardly a better time to be in the woods! The white-tail rut is like Christmas for most of us—wishing for that hot doe to lead a big buck under our tree. Our time is limited because of work, kids’ activities, and honey-dos, so we want to know when the best time is to be on-stand. Fellow hunters have asked, and I see it all over social media as well: “When do you think the rut’s gonna be this year?”

The short answer is: it’s the same time every year.

Countless people believe the rut peak has something to do with moon phase, temperature, mast, or some combination of these and other things. The one thing that triggers estrous in does (and many other changes in deer and other species) is photoperiod (length of daylight). To that end, the only thing that affects rut timing is geography (unless you’re in Florida—Florida deer are weird).

Multiple studies utilizing GPS collars, from Mississippi to Pennsylvania, have demonstrated that moon phase has no meaningful impact on deer behavior. Despite this, hunters will still argue over it as much as which rifle caliber is best.

Deer (and other species) evolved to have their young at an “ideal” time of year—when resources are most abundant. Why are all the wildlife babies born in the spring? Things are warming up and greening up. Producing milk for a fawn (or two or three) is incredibly costly to a doe in terms of energy—they need a lot of nutritious food to help them make milk and care for their young. When the fawns are weaned, they need that same food to grow and to build fat reserves before winter sets in. Here in Virginia, the peak of our “fawn drop” is about the first week of June, which coincides with this abundance of food and warmer temperatures. The moon phase or daily temperatures in November can vary a lot among years, but day length is pretty darn consistent.

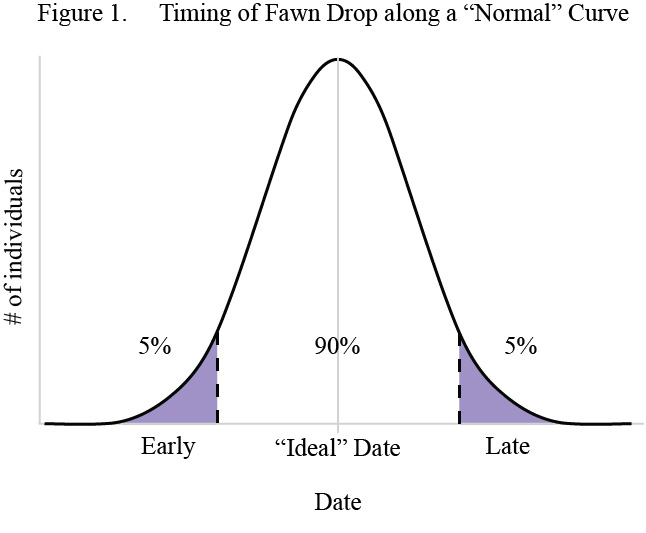

Obviously, not all fawns are born on the exact same day. Does are bred on different days, and length of pregnancy can vary. Fawning dates follow a bell curve. A “normal” bell curve for fawns being born will have majority of fawns hitting the ground around the average date, with fewer arriving at the “tails” of the curve (very early and very late). So, some fawns might be born in April or August, but most of them will be born around the first part of June in Virginia.

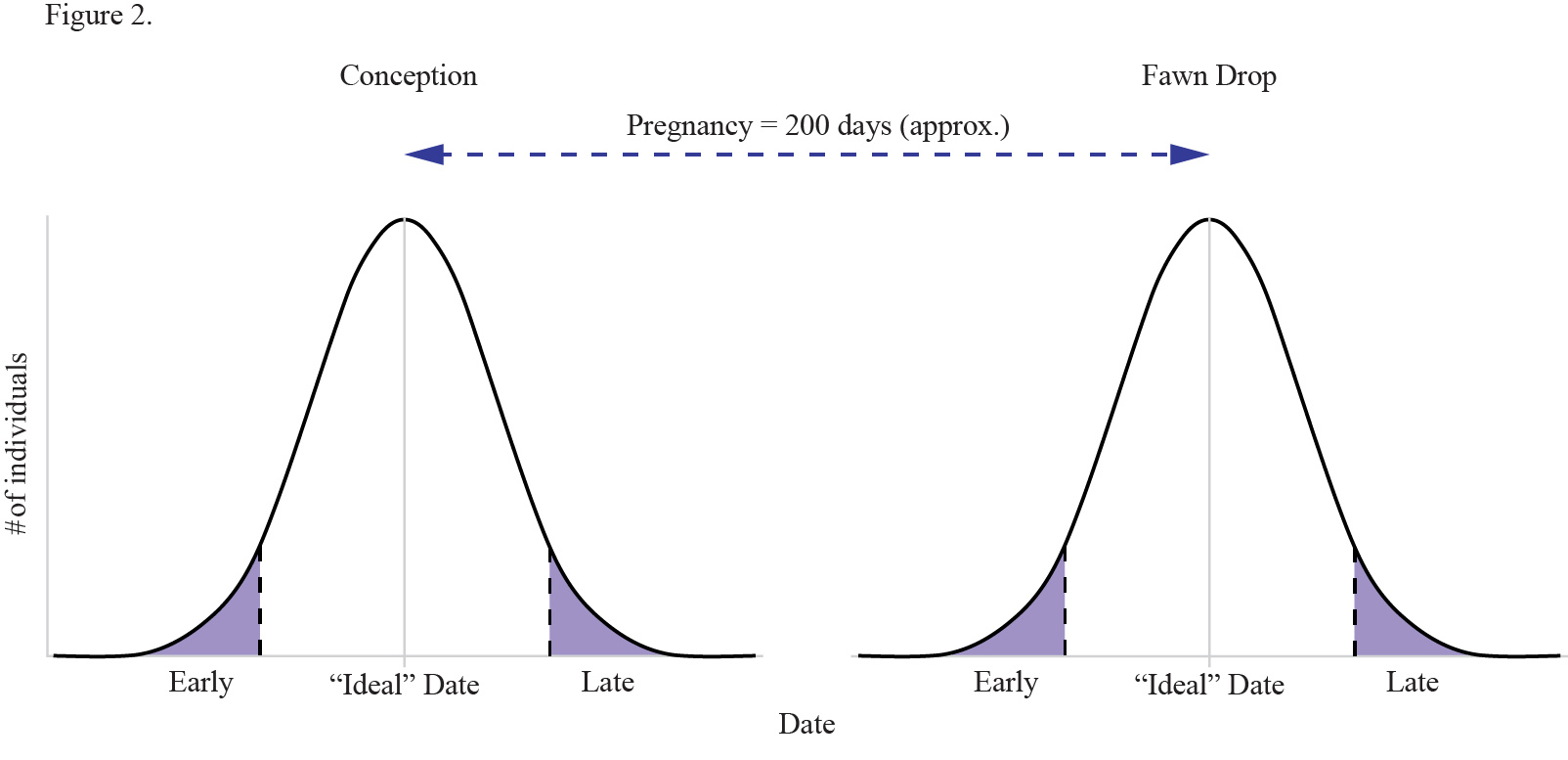

So, how does that translate to the rut? Well, the average gestation period (length of pregnancy) for a white-tailed doe is about 200 days. If we take that peak of the bell curve for the fawn drop and back-date that 200 days, we have our peak of breeding.

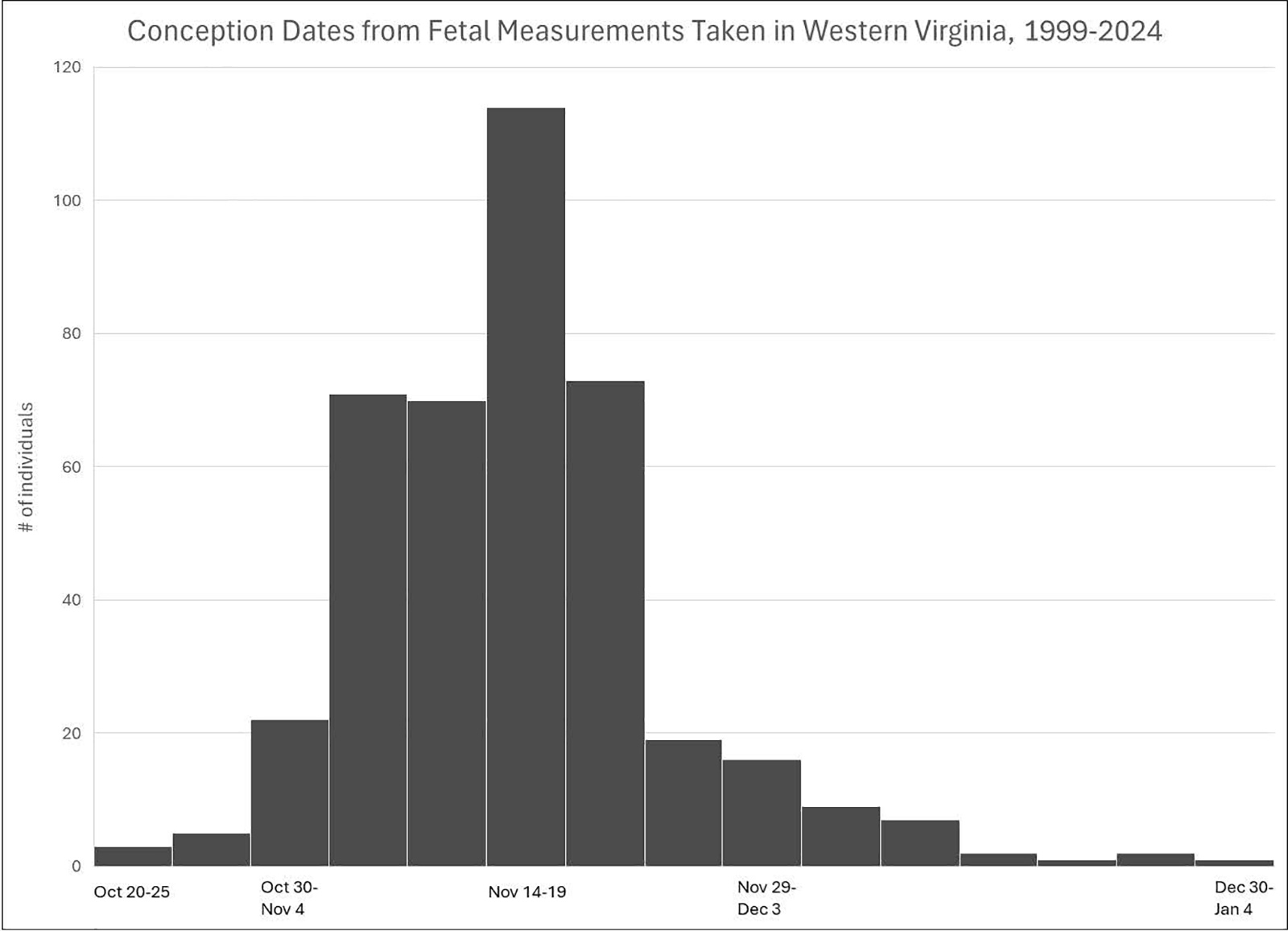

Again, a bell curve. Some does will be bred in October, some in December, but the peak is what statistically (and ecologically) has more lovesick bucks in a frenzy. If we call the peak of the fawn drop June 3, that puts the peak of conception at November 16. So, be in the deer stand as much as you can the weeks before, during, and after November 16… every year, no matter what the thermometer or moon chart says.

Justin Folks is DWR’s deer project leader.