Male Golden-winged Warbler. Photo by Baron Lin.

By Lesley Bulluck (VCU) and Sergio Harding (DWR)

A small lemon-capped songbird, the Golden-winged Warbler is declining rapidly across the Appalachian region. In Virginia, this bird breeds in high-elevation shrublands west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. We reached out to private landowners to see how they could help.

Male golden-winged warbler. Observed in Tazewell County, Virginia. Photo by Baron Lin.

Shrublands are open habitats with a mix of small-to-medium sized woody plants and wildflowers. In addition to the Golden-winged Warbler, they support a diversity of native Virginia wildlife. However, if left unmanaged by humans, or undisturbed by natural events like storms or wildfires, shrublands will grow over time and eventually revert to forest. Such habitat loss may be contributing to the decline of the Golden-winged Warbler and other shrubland-dependent birds.

The majority of Golden-winged Warblers in Virginia are found on private lands, and efforts to work with landowners are increasingly important to their conservation. In response to this need, DWR partnered with Lesley Bulluck and her student Hannah Coovert from Virginia Commonwealth University’s (VCU) Center for Environmental Studies to carry out a survey of private landowners in western Virginia in 2018. Efforts to create shrubby habitat on private lands have traditionally focused on forest landowners and the harvesting of timber. However, private lands with significant pasture cover present an additional opportunity to create shrubby habitat. A primary objective of the survey was to determine if there are any differences between landowners who are willing to carry out shrubland management in pastures and those willing to carry out forest management practices for the benefit of wildlife.

Left: There are a variety of ways to create and maintain high quality shrubland habitat, like that in the center of this aerial photograph. These include timber harvests, decreasing mowing and grazing intensity, using herbicides to control invasive species, and prescribed fire and machinery to thin shrubs when they become too overgrown. Right: This shrubland habitat is the result of reduced grazing intensity, though grazing was still actively occurring at the site. Notice the mix of forest, shrubs, saplings, and wildflowers – this is habitat for Golden-winged Warblers and many other types of wildlife.

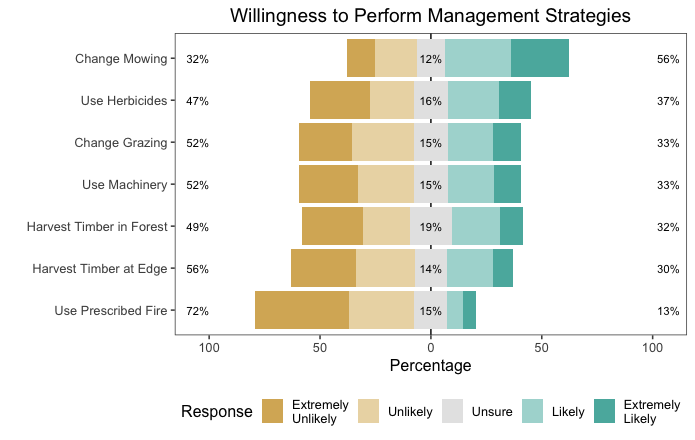

Over 500 landowners across five counties (Bath, Giles, Highland, Smyth and Tazewell) participated in the survey. The study found that landowners are most willing to modify their mowing practices (>50% of respondents) and least likely to carry out prescribed fire (13%). It also found that landowners who are willing to modify mowing and grazing practices tend to value ecological aspects of their land (water quality, pollinator habitat, presence of wildlife) whereas those most likely to harvest timber tend to value hunting and revenue from production on their land. Across all management options, landowners who have past experience with wildlife management are most likely to manage in the future.

Landowners differ in their willingness to carry out different management strategies to promote shrubland habitat (from a survey of Virginians in five western counties).

These results suggest that outreach efforts to engage landowners should include additional management options for creating shrubby habitat (i.e., changing mowing or grazing practices) and that highlighting the benefits to pollinator species and water quality could engage more landowners. With these findings in hand, DWR and VCU plan to work with partners to develop an outreach campaign which we hope will ultimately result in increased shrubland acreage for the benefit of Virginia’s wildlife.

How to help the Golden-winged Warbler

If you live in a high-elevation county, consider creating shrubland habitat on your property. This region is the focus for Golden-winged Warbler conservation in Virginia, and there are opportunities to get assistance through the Working Lands for Wildlife Program.

Participate in Virginia’s Second Breeding Bird Atlas, now in its third of 5 years, to help document the breeding status and distribution of Golden-winged Warblers and many other bird species in the Commonwealth.