By Stephen Living/DWR

We all need space. Plants need room to grow and animals need space to feed, grow, and raise young. The space different species need can be very different. A male black bear can use a territory covering an area anywhere from one to 290 square miles, while wood frogs may spend their lives in an an area of less then 1,000 square feet (on average). How much space animals need may vary depending on the time of year and their stage of life. Breeding chickadees may defend a breeding territory during the spring and summer, and form small flocks that roam a larger area during the winter.

If you’re trying to make your home a Habitat at Home for wildlife, understanding the space needs of wildlife you might hope to attract is important. A typical suburban yard won’t support a covey of bobwhite quail that typically need at least 30 acres with a variety of different kinds of cover to survive and reproduce. Yet even a small urban space can provide key habitat for pollinators like monarch butterflies to breed if native garden plants provide enough nectar for adults and enough milkweed for hungry caterpillars to munch on.

How much space is only one consideration. How that space is arranged is another thing to think about. Look at how different aspects of your habitat are arranged. Can wildlife move from one resource like food or water while staying near cover to hide from predators? A bird bath in the middle of an open lawn might make birds nervous and expose them to predators like hawks. That bird bath might not get very much use.

Locating a bird bath in the middle of a large yard where birds don’t have protective cover might reduce the usefulness of the bath for birds. Photo by Shutterstock

Where your space sits in the landscape is important as well. Wildlife and habitat don’t recognize property lines. If you have a large yard in a rural area that’s next to large, old fields with warm season grasses and native flowers, you might be able to help provide for bobwhite quail. Carolina chickadees need anywhere from three to six acres.

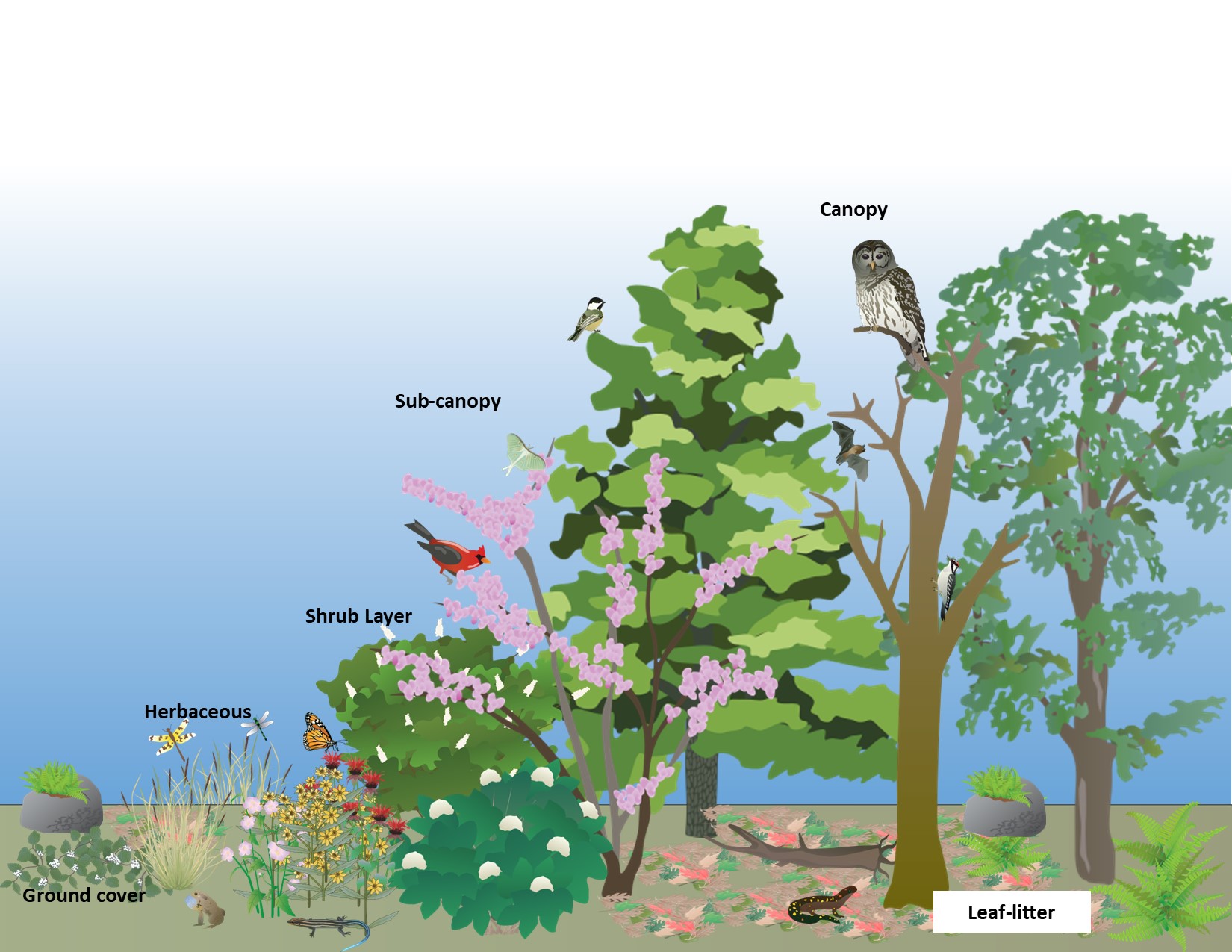

Creating layers of habitat can help provide for a many different species. Think of each habitat layer as another floor in a home or apartment building—it makes room for more tenants. Our Habitat at Home diagram works to mimic the layers that can be found in a forest.

Icons courtesy of Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/media-library)

This includes:

Canopy: This is the layer of mature trees that provide nesting, food, and cover.

Sub-canopy: These are smaller trees that grow underneath the canopy or along the edge of a forest

Shrub layer: Smaller, woody plants are important as cover, food, and a transition from the forest to more open habitat areas.

Herbaceous: This layer of green plants includes vines, grasses and flowering plants. It also provides nectar, seeds, and green foliage as food.

Leaf litter: Leaves, twigs, and other natural materials on the ground provide important cover and places for wildlife and native insects to live and overwinter. This is a great place for birds to forage.

Read also:

What is Habitat? Shelter Can Protect Wildlife

Stephen Living, the DWR habitat education coordinator, is a biologist and naturalist with a lifelong love of wildlife and nature that began in the woods and streams of his childhood.