Thanks to the dedication of an elite group of men and women, wildlife law enforcement in Virginia is better than ever.

by Bruce A. Lemmert

Precisely one century after Virginian Thomas Jefferson launched one of the boldest initiatives in the history of the United States, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Virginians were looking inward. In 1803, the frontier beckoned with limitless possibilities. In 1903, Virginians, and indeed all Americans, recognized that the frontier was settled. Natural resources would have to be protected and managed. Jefferson had predicted that it would take one hundred generations to settle what is now the western United States. Americans had peopled the continent in less than five generations. The realities of the myth of inexhaustibility were being realized.

Precisely one century after Virginian Thomas Jefferson launched one of the boldest initiatives in the history of the United States, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Virginians were looking inward. In 1803, the frontier beckoned with limitless possibilities. In 1903, Virginians, and indeed all Americans, recognized that the frontier was settled. Natural resources would have to be protected and managed. Jefferson had predicted that it would take one hundred generations to settle what is now the western United States. Americans had peopled the continent in less than five generations. The realities of the myth of inexhaustibility were being realized.

At the turn of the 20th century, the oldest continuously operating legislative body in North America, the Virginia General Assembly, was contemplating conservation measures. On the national level, forester Gifford Pinchot was making the term “conservation” a household word. Thanks to Pinchot, lay citizens readily recognized the term “conservation” to mean the management and protection of forests, wildlife, and parks. George Bird Grinnell, editor/owner of Forest and Stream magazine, championed the term “sportsman.” This term came to be recognized as a positive label for ethically behaved hunters and fishermen. And in the White House, President Theodore Roosevelt used his bully pulpit to make natural resource management an issue for which every American would be aware.

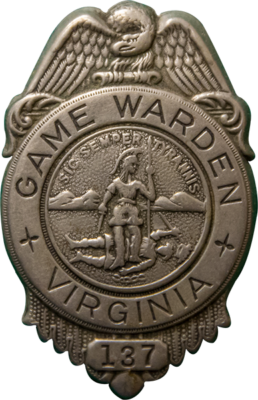

On May 14, 1903, the Virginia General Assembly enacted legislation, during a special session, to establish a statewide system of wildlife law enforcement officers to deal specifically with wildlife crime. From that point through 2007, these officers were called game wardens, now known as Conservation Police Officers.

In an effort to protect the state’s wildlife and natural resources, the Virginia General Assembly enacted legislation on May 14, 1903, that established a statewide system of law enforcement officers known as game wardens.

The state mandated that each city appoint two game wardens, and the counties were to appoint one game warden for each magisterial district. Since the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries would not come into being until 1916, the responsibility for hiring, firing, supervising, and paying for game wardens fell to the localities.

Not to be accused of unfunded mandates to the localities, the 1903 Virginia General Assembly also provided a means to pay for the new game wardens. An annual hunting license was created for non-residents only. The cost of this license was $10.00. This license entitled the non-resident hunter to “hunt and kill wild turkeys, pheasants or grouse, woodcock, partridges, quail, and other game birds during the open season.” For an additional sum of $15.00, the non-resident could purchase an additional license to hunt waterfowl and/or deer—subject, of course, to seasons and other provisions.

The clerk of court for each locality was assigned to sell the hunting licenses. The clerk was awarded 50 cents for each license sold. On April 1 of each year, the clerk shall ”pay in equal amounts to the said warden or wardens… such sum as may be in his hands arising from the issuance of said license: provided that no one warden shall receive more from this source than three hundred dollars in any one year.” In the event of a surplus after the game wardens were paid, a provision existed in Northampton and Accomac counties for the Eastern Shore Game Protective Association to use extra monies for the restocking of game.

As an added incentive for game wardens to apprehend wildlife law violators, a fee of $2.50 was to be assessed in every case of conviction and was paid directly to the warden securing the conviction.

Game wardens of 1903 were appointed to four-year terms. It was the sworn duty of wardens to enforce all statues of Virginia and of the United States for the protection and propagation of wild waterfowl, game birds, and game animals, or song and insectivorous birds. Any person found guilty of interfering with a game warden in the discharge of their duty, or of resisting arrest, was subject to a fine of from $5 to $50.

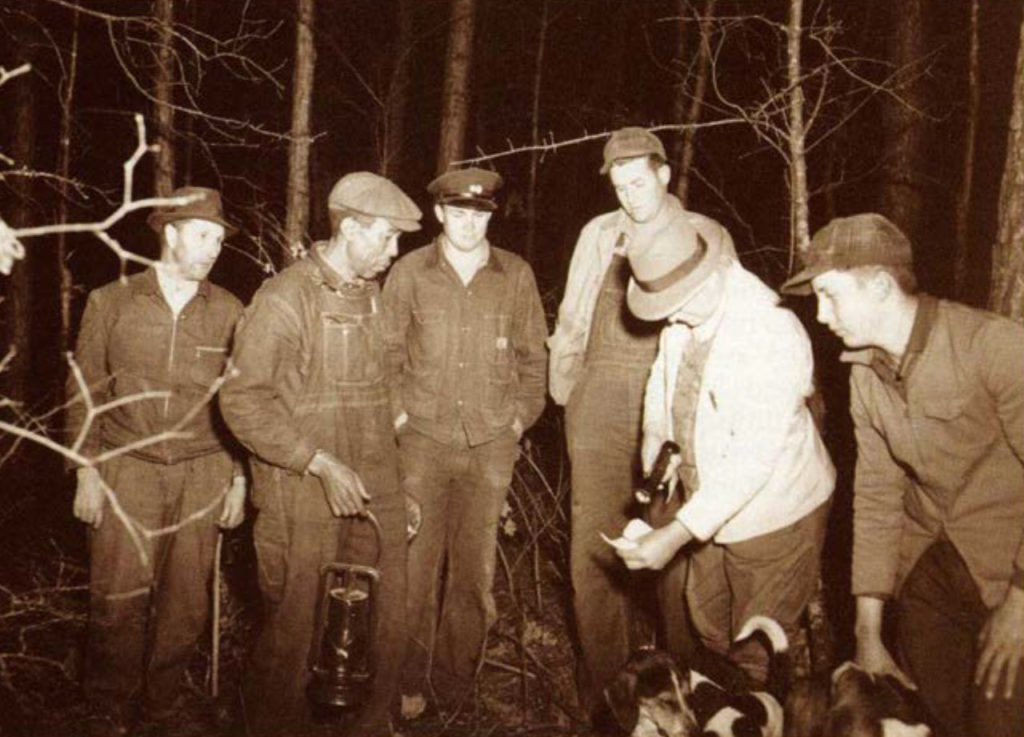

This photograph, taken over 60 years ago, shows two game wardens checking the hunting licenses of a group of raccoon hunters, during the middle of the night.

In the absence of a state wildlife agency, the General Assembly set the season dates for specific game. The localities were authorized to shorten hunting seasons in their respective jurisdiction if they saw fit to do so. An interesting aspect of the 1903 game laws was that it was unlawful to hunt or track grouse, quail, woodcock, or deer in the snow. Turkey, however, was specifically allowed to be hunted or tracked in the snow. Quail were the last wildlife species to be taken off the snow hunting restriction list, but that not until 1995.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act was not passed until 1918, so the 1903 Virginia General Assembly set the seasons for waterfowl and other migratory game birds without guidance from federal parameters. Waterfowl was delineated between summer wild waterfowl and winter wild waterfowl. Summer waterfowl was designated as wood ducks and winter waterfowl was apparently all other ducks and geese. The winter waterfowl season was October 16–March 31, and the wood duck season was August 2–December 31. Rails, mud hens, gallinules, plovers, surfbirds, snipe, sand pipers, willits, tattlers, and curlews could be hunted from February 16–March 31. There were no bag limits for any of these species, but possession outside the prescribed season was unlawful.

Those who love of hate the restriction on Sunday hunting can thank or condemn the 1903 General Assembly. The Sunday hunting restriction was adopted at this time. Additionally, it was deemed unlawful to hunt later than one half-hour after sunset or earlier than one half-hour before sunrise.

Being a game warden has never been your typical “9-to-5” job. It requires a special individual who is willing to look at his or her profession as not just a job, but also as a lifestyle.

In addition to the game wardens appointed by each local jurisdiction, several commanders of the oyster police boats were also constituted game wardens. These commanders of oyster police boats did not receive additional compensation, but were eligible for the $2.50 fee for each conviction. The so-called oyster navy was part of the Virginia Fisheries Commission, which was approved by the Virginia General Assembly on February 7, 1898. The Fisheries Commission had responsibility for oysters, clams, crabs, terrapin, and fish in waters of the state. The five-member board of the Fisheries Commission was authorized to hire captains of steamers and vessels for the protection and guarding of oyster beds in Virginia on the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

The Loudoun County Board of Supervisors wasted little time in acting on the May 14, 1903 legislation. On October 19, 1903, the Loudoun Board, meeting in Leesburg, shortened the upland bird season by one month. The Board also requested the Judge of Circuit Court to appoint Owen Orrison as game wardens of the Lovettsville District. On December 14, 1903, the Loudoun Board made their second game warden appointment, B.W. Presgraves, Jr., for Broad Run Magisterial District. Most assuredly, other localities were also busy complying with the 1903 mandate.

What was it like to be a game warden in 1903? Today’s game warden is excessively dependent on the telephone, the automobile, and radio communications. Consider this: in 1900, there were 1,356 telephones in the United States and there were only 8,000 automobiles in the entire nation. An outhouse served most homes. There was a grand total of one mile of smooth paved road in the U.S. Two-way radios were non-existent. Electricity didn’t go beyond most major cities, so it was not a worry about a place to plug in the radio, television, or computers, because none of these existed. Life expectancy for men was 47 years and 51 years for women.

Game Warden Owen Orrison most likely relied on word of mouth, a horse, and boot leather to do his job. Not surprisingly, word of mouth information and a good pair of boots is still the game warden’s best friend. The horse is lost of posterity, with mixed emotions. It would be safe to say that Orrison had a penchant for the outdoors. He assuredly had another profession. It is unlikely that Orrison earned even close to the $300 per year allowable as game warden. It is doubtful that many non-resident hunting licenses were sold in 1903. The masses simply didn’t have the money or the mobility. Compliance was most assuredly not automatic. Ten dollars was a lot of money. Twenty-five dollars was a whole lot of money. The hunting of waterfowl by non-residents may have been the only exception and this only in some of the tidewater counties.

One of the first hunting seasons established by the General Assembly in 1903, and enforced by the newly-established game wardens, was for waterfowl and other migratory birds.

Wildlife law was legislated in Virginia as early as 1632. Because of conflict and opportunity in an agrarian society much wildlife law followed. Some may ask, why did it take so long to hire game wardens? Of course, the other side of that question is why do we need game wardens at all? After all, a sheriff is already being paid to enforce the law. The law is just the law; let the sheriff enforce wildlife law. The answer is many faceted, but in essence, those people interested in protecting or managing wildlife realized that unless someone was specifically assigned to enforce wildlife law, it simply would not get done.

Why would wildlife law not be enforced? John Reiger answers this question best in his important book, American Sportsman and the Origins of Conservation. “If sportsmen failed to regulate themselves, no one else would, for they lived in a country characterized, first, by a Judeo-Christian tradition that separated man from nature and sanctified his dominion over it; second, by a laissez-faire economic order that encouraged irresponsible use of resources; third, by weak institutions, including the federal government, that seemed unwilling of unable to protect wildlife and habitat; and fourth by a heritage of opposition to any restraint on ‘freedom’, particularly that vestige of European tyranny, the game law.” So, in addition to the points Reiger makes, the elected sheriff recognizes that most wildlife crime not only goes unreported, it goes unnoticed. And the harried sheriff may be thinking, “Is a crime really a crime if no one knows about it? Would not it be best to well enough alone?” From a game warden’s perspective, and in defense of our many good sheriffs through the ages, wildlife law enforcement is an extremely time-consuming endeavor and it literally takes a single-minded effort to be effected. A sheriff concentrating on deer poaching was not likely to be re-elected, especially if some other phase of his law enforcement duties were neglected.

On February 8, 1908, the General Assembly of Virginia passed legislation effective immediately, to empower game wardens to enforce all laws for the protection of fish in the waters of the Commonwealth.

There was no provision for any increased pay to the game warden for this added responsibility, except that the warden was to receive for such service one-half of the fine imposed by the court for any conviction. The requirement for any type of license to fish was not made until 1928.

“Be it enacted (March 11, 1916) by the general assembly of Virginia, that a State department of game and inland fisheries is hereby created.” With this landmark legislation, a resident hunting license was created. The cost of the resident hunting license for $3.00 for a statewide license, and $1.00 for a county of resident license. All license fees, including non-resident licenses, went to the Game Protection Fund, used to finance the new department. The non-resident license remained at $10, and the provision for a waterfowl and/or deer license for an additional $15 was dropped.

Each county and city was to provide to the commissioner of the new department a list of ten suitable persons for the position of game warden for each jurisdiction. Two types of wardens were designated as regular wardens and special wardens. Regular and special wardens were to be appointed as the commissioned may deem necessary, but at least one regular game warden was to be appointed for each county. The commissioner was directed to make appointments based upon the applicant’s practical knowledge of the animal, bird, and fish life and game laws of the State.

Regular wardens were to receive a salary of not more than $50 per month in local jurisdictions of less than 20,000 inhabitants. Regular game wardens in localities of more than 20,000 inhabitants could be paid up to $60 per month. Special game wardens received up to $3 per day, plus expenses for their services when needed. Special wardens were to serve under the direction of the regular wardens. The $2.50 conviction fee was left in place for game wardens, and additionally special wardens were to collect 50 percent of any fines paid by a convicted defendant.

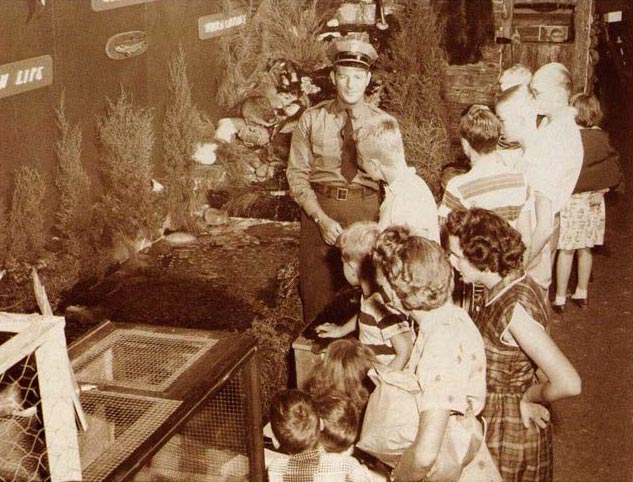

The commissioner was directed to enforce all laws for the protection, propagation, and preservation of wild animals and birds, and all laws relating to fish in waters above tidewater, and assist with enforcing dog laws and forestry laws. He was given authority to propagate game and fish, purchase specimens, engage the necessary employees, erect buildings, and lease or purchase necessary lands. The commissioner may adopt such means and make such expenditures for the purpose of restocking any depleted species or to introduce new species of game animals, birds, or fish. The Department was given authority to close seasons on game or fish in any county or in any stream for periods of from two to five years. Authority was given for public relations-type activities, especially for the benefit of schoolchildren and agriculturists. In conclusion of the commissioner’s duties, it was stated, “He shall foster the conservation of all wild life in the State in every reasonable way.”

The commissioner was directed to enforce all laws for the protection, propagation, and preservation of wild animals and birds, and all laws relating to fish in waters above tidewater, and assist with enforcing dog laws and forestry laws. He was given authority to propagate game and fish, purchase specimens, engage the necessary employees, erect buildings, and lease or purchase necessary lands. The commissioner may adopt such means and make such expenditures for the purpose of restocking any depleted species or to introduce new species of game animals, birds, or fish. The Department was given authority to close seasons on game or fish in any county or in any stream for periods of from two to five years. Authority was given for public relations-type activities, especially for the benefit of schoolchildren and agriculturists. In conclusion of the commissioner’s duties, it was stated, “He shall foster the conservation of all wild life in the State in every reasonable way.”

On March 21, 1916, the Virginia General Assembly changed the mandate of the Board of Fisheries (or the Virginia Fisheries Commission as it was interchangeably called), to reflect the creation of the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. In the initial mandate creating the Fisheries Commission, duties of the agency were to include responsibility for fisheries in “water of this state.” Now, in 1916, the Fisheries Commission duties were amended to include only “the fisheries of tidewater of Virginia.” Not immediately, but by 1938, the delineation of where inland fisheries stopped and tidewater fisheries began was in contention. Most likely, 1938 brought this contention about not by squabbles between the two resource agencies but by the enforcement with the fishing public of the so-called “inland fishing license,” which had been in effect for 10 years. One section of the State Code defined inland waters to mean and include all waters above tidewater and the brackish and fresh water streams, creeks, bays (including Back Bay), inlets, and ponds in the tidewater counties. Attorney General John R. Saunders held that inland waters included all fresh and brackish waters in Tidewater Virginia as that section was defined. On March 31, 1938, the General Assembly directed the two Commissioners to delineate an agreed-upon boundary between the jurisdictions of the two agencies.

Game wardens have always been recognized for their efforts in protecting wildlife, and the knowledge they provide about the outdoors and wildlife continues to be an important source of education that is shared with everyone from landowners to schoolchildren.

It took 13 years, between when game wardens and the first hunting licenses in Virginia were created, until when a full-fledged wildlife agency was established. Why was a state agency needed when a statewide system of wildlife law, policy, funding, and enforcement already existed? The short answer is that the system set in place in 1903 was piecemeal and inadequate. The wildlife mission was too important. The 1916 General Assembly realized that a full time, statewide agency with a focused mission was needed. The General Assembly itself was simply not structured to deal with the many and varied problems that existed for managing wildlife resources on a day-to-day basis.

The game warden system established in 1903 could not be effectively funded on the backs of non-residents and poachers. There simply were not enough non-resident hunters and hopefully not enough wildlife law violators to meaningfully fund a wildlife law enforcement effort. Game wardens, for the most part, were pursuing the profession on a part-time basis. This was a matter of survival and of reality. Game warden work, in order to be effective, must be single-minded and full time. One game warden described work during hunting season as “Like riding a bucking bronco. You are either in the saddle with total concentration… or in the dirt looking up and wondering what happened.”

In order to establish a comprehensive wildlife agency with fully-funded law enforcement, Virginians would have to ante up. This they did. With the establishment of the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries in 1916, it was hunters alone who first footed the bill. Soon afterward, trappers and anglers began financially supporting the effort with the establishment of the combination license in 1928.

A century of game wardens. This we celebrate. The conservation efforts of the past one hundred years have been replete with stories of success and, yes, of failure too. The path certainly wasn’t always straight. There was no road map to success. The inside cover of the 1926 department law pamphlet lists some benefits of game law enforcement. One of the benefits listed was that game laws and their proper enforcement “Makes Virginia attractive to outsiders and a still-sweeter place for Virginians.” Yes, through the blood, sweat, and tears of many a game warden, I think that is true.

This article originally appeared under the title “Virginia Game Wardens Celebrate One Hundred Years” in the May 2003 issue of Virginia Wildlife Magazine. A copy of the original article may be viewed here. The author of this article, Bruce Lemmert, served as a Virginia Game Warden in Loudoun County, starting in 1989 and was named the 1997 Wildlife Officer of the Year for the North American Wildlife Enforcement Officers Association. He was also the recipient of the Guy Bradley Award, from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Foundation.