An Eastern garter snake, the state snake of Virginia, can be found in suburban gardens and around houses and barns, but is harmless. Photo by Douglas Hayes

By Marle A. Condon

One evening as it was getting dark, I caught sight through the kitchen window of a red fox that frequents my yard. As it went over a log, it jumped as if it had stepped upon something.

The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) kept returning to the spot, obviously curious about what was there, yet reticent to get too close. Naturally I wanted to know what was going on. So as soon as the fox left, out I went with flashlight in hand. The object of the fox’s attention turned out to be an adult Northern copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix)!

An Eastern copperhead. Photo by John White

As I watched, the three-foot-long reptile headed off toward the front yard where I’d seen a copperhead earlier in the summer. It had not bitten the fox, even though the canine must have stepped on or very close to it. And the snake exhibited no interest in me, as I stood several feet away.

There’s a practical explanation for the snake’s behavior: Snakes have no interest in anything they do not perceive as food. Foxes and humans are not food to a copperhead, so it would much prefer to avoid them. It will, however, defend itself if it feels threatened.

The aggressiveness of snakes, particularly the cottonmouth, is rooted in folklore and greatly over-exaggerated. On average, about six people are killed by snakes each year in the entire United States. In contrast, dog attacks account for about 21 deaths a year and lightning strikes, about 54. So it’s truly a shame that people tend to fear snakes to the extent they do.

Why do we fear animals that are so much smaller than we are? Some researchers believe that the human fear of snakes is learned. If people around us fear something, we’re going to believe we should fear it as well. Others believe it is inherent; an evolutionary trait to protect us from harm. But we may possess an inherent fear of snakes simply because these animals are so different from us.

The movement of a snake’s body is unlike that of most animals we often see. Snakes don’t have legs but they can move swiftly along the ground. Contrary to urban legend, snakes do not chase people. The fastest snake in Virginia, which is most likely the northern black racer (Coluber constrictor), reaches a top crawling speed of only about four miles per hour. That isn’t much faster than a brisk walk!

Several snake species even climb trees regularly, and most are excellent swimmers. Their sinuous form allows snakes to wind around objects. Some, in fact, employ this ability as a method to capture their prey. Of course, their manner of feeding—swallowing an animal whole—may seem particularly repulsive to us.

But the reality is that snakes are extremely important to the proper functioning of the environment as a whole, as well as our piece of it. A question that I always get asked when I give a nature or gardening talk: “How do you deal with mice [actually, voles] in the garden?”

I respond by asking if the questioner kills snakes and every time, I receive “yes” for an answer. If you kill snakes (which in most circumstances is illegal in Virginia), you will very likely experience an increase of voles in your yard. There’s a direct link between these rodents and snakes that cannot be broken without serious consequences—not only to you and your plants, but also to the voles and to the larger environment.

Because so many kinds of animals feed upon them, rodents need to multiply frequently. Almost all of their predators, however, are much too large to go down into a long, winding vole burrow in the ground. A snake is properly sized with a sinuous body (the necessary anatomy), which allows it to do so. In other words, snakes are efficient predators of rodents.

Therefore, if you rid your yard of these reptiles, you break the connection between snakes and rodents that helps to keep the population of voles at a sustainable level. “By sustainable,” I am referring to a vole population that the environment can support in a healthy manner.

Living With Snakes

There are 30 species of snakes in Virginia. Several of them feed quite a bit upon rodents and thus are important to limiting rodent populations: the Eastern ratsnake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis), mole kingsnake (Lampropeltis calligaster), cornsnake (Pantherophis guttatus), Northern copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix), and timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus). Only the copperhead and timber rattlesnake are venomous, and if you are careful, you can co-exist with them peacefully.

An Eastern ratsnake. Photo by Paul Sattler

I’ve lived in my house for almost three decades without experiencing any problems with the copperheads seen occasionally in my wildlife-friendly yard. Although these snakes can cause humans serious harm, it’s highly unlikely to happen if you follow three logical, simple rules.

When you see a venomous snake (or any snake), common sense dictates that you leave it alone. Most people who get bitten by snakes are either trying to kill the snake or move it.

Obviously a snake is going to try to protect itself under these circumstances. You should stay several feet away from a snake, because a coiled animal can strike about half of its body length. If you are within two feet of a four-foot snake, for example, it could bite you.

Second, pay attention to where you place your feet. Getting into the habit of watching where you step is a good idea, even if you aren’t concerned about venomous snakes. There are many critters on the ground that you needn’t step on and injure or kill.

Third, never place your hands or feet into areas such as tall plants or a woodpile where you can’t see what’s living inside. There are quite a few animals that—out of fear—as your foot or hand approaches will give you a sting or bite that may not be deadly but, nonetheless, will hurt quite a bit.

Educate Yourself

Can children learn these rules? Absolutely, just as they learn to never cross the street without looking both ways first. In fact, statistics show that children are far more likely to be run over by their parents in their own driveway than they are to be harmed by a snake… or injured or killed by pets such as dogs, cats, and horses… or even to be hit by lightning. Our fear of snakes is way out of proportion to the actual likelihood of being harmed by them.

A big step you can take to conquer your fear is to learn as much as you can about snakes. Recognizing their usefulness is a great place to start.

Gardeners, for example, value earthworms and toads. Earthworms recycle organic matter back into the soil, and in the process, improve its tilth (looseness of individual soil particles) and nutrient value. Toads help to limit insects, some of which may harm plants if there are too many of these arthropods. However, even earthworms and toads need to be limited for their own benefit.

When the wormsnake (Carphophis amoenus) and the smooth earthsnake (Virginia valeriae) reptiles found throughout most of Virginia—feed upon earthworms, they prevent them from running out of food and starving or becoming diseased (nature’s solution to overpopulation). Similarly, snakes may help to keep populations of toads in check.

Eastern wormsnake. Photo by J.D. Willson

Most snakes will eat whatever they can catch—including fishes, salamanders, lizards, nails, insect larvae, and spiders—and therefore keep many, many kinds of animals from overpopulating, and thus overwhelming, the environment. Their presence in the home landscape helps the natural food web function.

And, of course, the snakes themselves are an important food source for animals such as foxes, hawks, opossums, and raccoons. Even other snakes, such as the kingsnake, will feed upon venomous snakes.

Consider giving snakes the space they need to go about their business. They, in turn, will keep select populations in check, which benefits all kinds of wildlife (including the human kind).

We should—and we can—co-exist with these fascinating and hardworking animals.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2014 issue of Virginia Wildlife magazine. Interested in more about Virginia’s snakes? Make sure to get a copy of “Guide to Snakes and Lizards of Virginia” for more than 170 photos covering the ecology, distribution and conservation of Virginia’s 32 species of snake and nine species of lizard.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

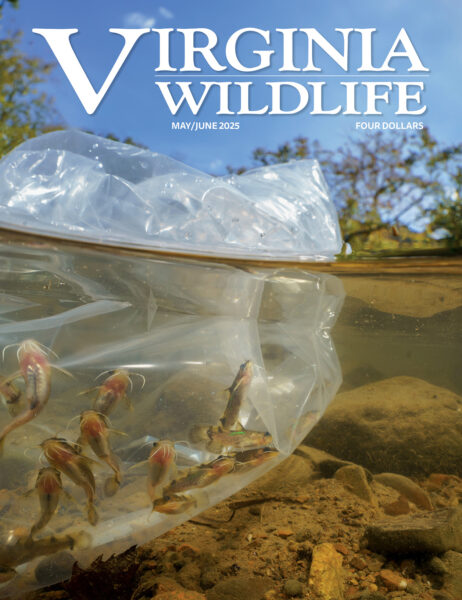

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe