As the Endangered Species Act marks its 50th anniversary, wildlife conservationists celebrate its remarkable achievements and reflect on what has yet to be done.

By Molly Kirk/DWR

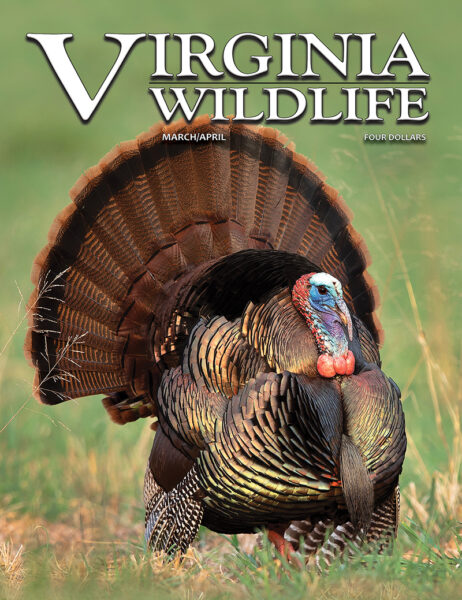

It’s tempting to tell the story of 50 years of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) by shining the spotlight on its poster child, the iconic bald eagle. True, the bald eagle’s remarkable recovery as a species in those 50 years testifies to the effectiveness of the ESA’s protections. But, like so many things in wildlife conservation, the stories of many other endangered species are much more complicated.

At the time that the ESA was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Nixon in 1973, around 30 breeding pairs of bald eagles were known in Virginia. A few years later, biologists could only find a literal handful of Appalachian monkeyface mussels in one river in the commonwealth. Both species were added to the Endangered and Threatened Species List in the late ’70s.

After concerted conservation efforts, in 2007 the bald eagle was removed from the federal Endangered and Threatened Species List. Virginia removed it from the Virginia List of Endangered and Threatened Species in 2013. By 2021, surveys had counted more than 1,500 breeding pairs of bald eagles in Virginia. “I can’t really think of a greater wildlife management success story; it’s one of the biggest,” said Jeff Cooper, Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ (DWR) non-game bird project coordinator.

Today, the rarely seen Appalachian monkeyface mussels are still just as scarce as they were 50 years ago. Almost. It wasn’t until the summer of 2023 that the Appalachian monkeyface populations got a boost when DWR biologists and partners released 125 juveniles of the species into the Clinch River. It had taken those biologists three years to find just eight live individuals of the species to hold in captivity at DWR’s Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center (AWCC) for propagation, and a significant amount of effort to discover the mechanism of the species’ reproduction.

DWR staff, partners, and volunteers survey for freshwater mussels in a Western Virginia river. Surveys help scientists to monitor the health of mussels, other aquatic species, and the quality of the river habitat itself. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

The Road Less Taken

The bald eagle’s comeback owes much to a federal ban of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), an insecticide that was a major contributor to the bald eagle’s population decline. But habitat destruction and degradation and illegal shooting had also negatively impacted the eagle population. The ESA provided habitat protection regulations that allowed DWR to protect bald eagle nesting and roosting sites in Virginia with time-of-year restrictions during breeding seasons and spatial restrictions, preventing certain activities within a specific area of a known bald eagle nesting or roosting site.

“Immediately, the DDT ban was effective because as soon as those birds could get that chemical out of their systems, they could raise young. So even if the habitat wasn’t perfect, as long as they could get those young up and flighted, we were building the population,” said Amy Martin, DWR manager of the non-game and endangered species program. “But without the habitat protection also afforded under the ESA, they would not have been able to rebound to the extent that they have. They needed somewhere to come back and nest every year and have all the resources they need, and protecting their habitat allowed that.”

Banning DDT and implementing habitat protections were easily identifiable and readily effective steps to recover the bald eagle, but for many species, the route to rebound isn’t so clear. For decades, biologists interested in recovering the Appalachian monkeyface mussel faced challenges in a lack of funding and a lack of information about the species’ reproduction. It’s also much more difficult to protect large areas of underwater habitat than a tree with a nest in it.

“It’s been 50 years, and this is the first significant recovery action we’ve been able to take for this animal,” said Tim Lane, DWR’s southwest Virginia mussel recovery coordinator, of the Appalachian monkeyface. “The main reason it took so long to get to this point is that the Appalachian monkeyface doesn’t have a straightforward propagation process. Some species, it’s like baking a cake for us—we know what to use and how to do it. This species, it was like astrophysics. It was close to impossible to figure out how to produce them.”

“It takes time because we don’t have a lot of money, and we don’t really have to a lot of people to do the work,” said Becky Gwynn, DWR Deputy Director. “That is really one of the challenges—for as highlighted as these animals become when they become listed, it’s probably one of the least-funded programs, at both the state and national levels.”

A Map to Recovery

The ESA was enormously popular when it passed in 1973, getting 390 yay votes in the House, unanimous votes to pass in the Senate, and being signed by President Richard Nixon. It was originally aimed to protect a few highly visible and charismatic U.S. species that were in drastic danger of extinction— the bald eagle, the California condor, and the Florida panther. In its 50 years, it has added more and more species and become more entwined in partisan political conflicts.

Gwynn described the ESA as “a legislative framework for the protection and recovery of species that have become so imperiled that their existence in the United States is uncertain.” According to the ESA, an “endangered” species is one that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range. A “threatened” species is one that is likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. In order to receive the protections provided by the ESA, a species must be added to the federal list of threatened and endangered wildlife and plants.

Once a species is included on the federal list as endangered or threatened, a recovery plan and a recovery implementation strategy for it are written, detailing what steps might be taken to help maintain or improve the species’ population. “There’s a blueprint for hopefully turning around the downward trajectory of a species’ population,” said Gwynn. “The goal is always recovering it to a point where it’s no longer necessary for the species to have the protection of the ESA, or de-listing it. DWR’s goal, ultimately, is to maintain the diversity of the Commonwealth’s wildlife.”

After a species’ recovery plan has been mapped out, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) looks to state agencies like DWR; other state, local, and federal agencies; and non-governmental organizations to help implement the plan.

There are currently 1,683 species on the federal Endangered and Threatened Species List. Obviously, not all of those species exist in Virginia, but there are also some native Virginia species that are imperiled within the state’s borders but not on a nationwide basis. So, a Virginia Endangered and Threatened Species List also exists. The Board of DWR takes action periodically to update and include federally listed species, as well as add Virginia-specific endangered and threatened species. As of March 2023, there are currently 90 species listed as state-endangered in Virginia, with 43 species listed as state-threatened.

Where the ESA Meets the Road

As the state agency tasked with the protection of Virginia’s wildlife, DWR, through its Environmental Services Section (ESS) and under the ESA, reviews and makes recommendations on any land- or water disturbing project that may impact Virginia’s wildlife species or their habitat. “It’s not just land development, but also water intakes, energy production, discharges into water, or outflows into water all of those have permits wrapped around them,” said Martin. “We don’t see all projects—there are lots of projects that don’t have any sort of nexus with us, for example if they don’t have any water quality permits or they’re not required to do any environmental assessments or impact reports. But we see a lot of them.”

DWR’s ESS staff reviews the data and the project site to determine if there might be impacts on a wildlife species, especially a state-threatened or endangered species. “If so, we will make recommendations to avoid those impacts or minimize them to the greatest extent possible,” Martin said. DWR serves as a consulting agency and works with regulatory authorities proactively to have them incorporate DWR’s recommendations as part of the permit requirements.

DWR’s Environmental Services biologists, along with staff from other agencies, assess a site for wildlife habitat and discuss site development plans to inform DWR’s recommendations for avoiding and minimizing impacts upon wildlife and their habitats on site.

“We do get pushback periodically,” Martin said. “Usually, we’ll get sort of creative and try to figure out a way to help them either modify the project or do things a little bit differently. It’s not our job to come in and stop a project. Our job is to guide the project to be as protective of potentially impacted wildlife or habitats as possible. There are situations where maybe a permit applicant can’t minimize impacts to the degree that we think they should. And in those cases, we might ask for mitigation for those impacts,” Martin continued.

For example, an ESS review determined that a project would impact habitat for the Rafinesque’s big eared bat, a state-endangered species. The permit applicant worked with the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation’s (DCR) Natural Heritage Division to help fund a land purchase that expanded a natural preserve with ideal habitat for that species. “It’s not about making DWR whole, it’s about making the species whole and their habitat whole,” Martin said. “Working with partners and other state agencies is part of that. We just want to see that sort of conservation achieved.”

DWR’s goal in consulting on projects is to protect threatened or endangered wildlife that they might impact, such as the Rafinesque’s big-eared bat. Photo by Ken Conger/DWR

Braven Beaty of The Nature Conservancy has worked with DWR on endangered and threatened species in Southwest Virginia. “What’s focused on in the press is the concept that ESA is a regulatory barrier, but the flip side has been, in our area at least, that it’s actually provided resources to help benefit communities in ways that never would have happened otherwise,” Beaty noted. He pointed out that due to the ESA, cattle ranchers in the area have financial incentives to incorporate practices and infrastructure that improve water quality.

“There’s an availability of resources that actually help your average citizen do a better job of managing their property and making it more productive,” he said.

More We Could Be Doing

The other way the ESA enables conservation is through specific funding pathways to agencies through grants. “That funding supports everything from land protection to population surveys to active management like prescribed fire, where we’re trying to restore habitats or create a more perfect habitat for a particular species,” said Gwynn.

In addition, the ESA requires financial mitigation for activities that negatively affect endangered or threatened species. Those mitigation funds go toward the conservation efforts of those species. For example, if a company spills toxic chemicals into a river, killing the freshwater mussels in a stretch of that waterway, their settlement under the ESA can help fund freshwater mussel restoration research and implementation. DWR’s Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center has become a nationally recognized leader in freshwater mussel restoration with their innovative work with critically imperiled mussel species like the Appalachian monkeyface in part due to funding from settlements around toxic spills in the upper Tennessee River watershed.

But, while the funding exists, it is by no means sufficient. And Virginia has to compete nationally with other states for the ESA grant funding. The majority of DWR’s operating budget is funded by the sales of hunting and fishing licenses and boat registrations— those funds primarily go toward programs within those activities. “Out of a 68-million-dollar budget, we spend about two and half million dollars on 855 species of greatest conservation need each year, funds that come largely from federal grants,” Gwynn noted. “It’s important for us to be stewards of all wildlife, not just some of the wildlife.”

Red-cockaded woodpeckers, a federally and state-endangered species, have benefitted from habitat work done by DWR and partners. Here’ Becky Gwynn, DWR deputy director, holds some chicks as Dr. Bryan Watts of the Center of Conservation Biology looks on.

That lack of funding for endangered and threatened Virginia species results in a lack of staffing dedicated to those species at DWR. Just one biologist is responsible for all of the Commonwealth’s bat populations. The state herpetologist is tasked with monitoring and protecting all of the turtle, snake, and salamander populations. Martin noted that just two ESS specialists at DWR evaluate and research more than 3,000 project review requests each year.

“The money that’s dedicated toward imperiled species is just significantly lacking,” said Martin. “We always spend what we have to keep things going, but there’s so much more we could be doing.”

The Path Forward

One of the biggest successes of the ESA is one that isn’t explicitly written in its text—it’s the marked growth in public awareness about imperiled species. “At the time the ESA was passed, I don’t think people had a sense that there were immediate threats to wildlife in and around where they live,” said Bill Williams, past president of Virginia Society of Ornithology. “The ESA and its role in bald eagle recovery served as a great model for the general public to understand that that effectively applied regulations can save, or at least stabilize, a species of animal.”

Martin noted that during her 22-year tenure at DWR, she’s seen attitudes shift a bit, such as when private landowners are proud of bald eagles nesting on their land, when a few decades ago they were angry the land couldn’t be developed. “We’re getting more support for the consideration of indirect effects. When I first started, unless you were actually touching the animal, no one would listen to you,” she said. “Now people are starting to say, ‘Riparian buffers to help improve water quality so the animal can live—that makes sense.’ ”

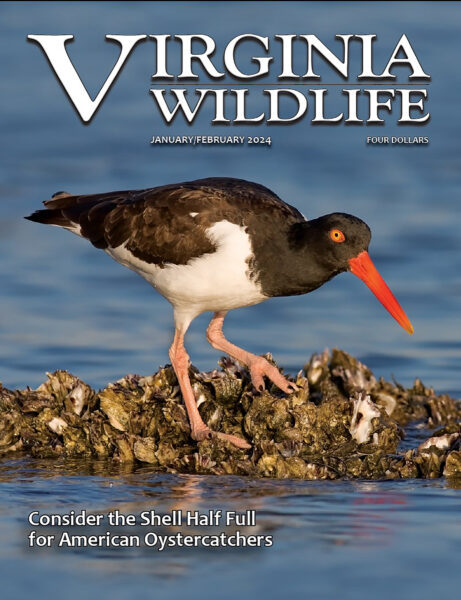

But therein lies one of the pickles of the ESA. It’s easy to get the public to cheerlead for and support regulations around high-profile species like the bald eagle. But what about the Appalachian monkeyface mussel, or the eastern black rail, a tiny, rarely seen shorebird? Williams heard a black rail call once while surveying bird populations on a barrier island. “But I’ve never seen one—that’s how cryptic they are,” he said. “That’s a tough sell for folks, to say that we need to take steps to save this little thing that lives in a marsh, is no bigger than your fist, and is very rarely seen even by avid birdwatchers.”

Another challenge for some endangered and threatened species is that their trajectory for recovery is much longer than that of the bald eagle. It’s tough for the public to think in that extended timeframe. “When you get to the point where an animal has to be protected under the ESA, the recovery is incredibly long, and it’s expensive,” said Gwynn. “You won’t necessarily be able to check a box and call it done in five years or even a decade. It took us multiple decades to reverse the bald eagle population to the point where it could be downlisted from endangered to threatened and then finally, to the point where it could be de-listed. Appalachian monkeyface mussels may not be recovered sufficiently to de-list the species in our lifetimes, but we at least have a path forward.”

How You Can Help Virginia’s Threatened and Endangered Species

Donations to DWR’s Non-Game Fund are tax-deductible and go directly to the conservation of non-game species and their habitats.

Donate online: virginiawildlife.gov/nongame-donation

Or send a check payable to Virginia Non-Game Program to DWR Non-Game Program, P.O. Box 90778, Henrico, VA 23228-0778

This article appeared in the November/December 2023 issue of Virginia Wildlife magazine.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe