One crisp fall morning and a doe forever shifted this woman’s relationship with hunting.

By Shannon Brooks

Photos by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

I got my start in hunting thanks to a wayward rooster.

Jackson was an enormous rooster that ruled our home poultry flock some 20 years ago. He was best known for his beautiful gray plumage, oversized ego, and a mean streak a mile wide. When he attacked our preschool-aged daughter one fall morning, I decided it was time to send Jackson off to “freezer camp.” I made a mental note to do the deed the next Saturday morning.

Unfortunately, when I went outside early the following Saturday morning (still in my pajamas) to open the coop and release the chickens, I had forgotten all about my plan to dispose of Jackson. But he promptly reminded me by leaping into the air and flogging me about the head and shoulders. Livid and more determined than ever to remove Jackson from the gene pool, I fetched the “varmint rifle” from the gun safe and came back outside just in time to see Jackson hightailing it into the woods. I pursued him, but his mottled gray coloring proved to be perfect camouflage in the November woods, leaving me straining to hear the slightest rustle that might signify a chicken reconsidering his life choices.

A few moments’ thought brought much-needed clarity: Today was the first day of deer season and we had given permission for the cousins to hunt our property. It was entirely possible that one of them was even now looking on from a well-concealed tree stand or trail camera, watching me stand in the woods in my bright blue flannel snowflake pajamas and flipflops, holding a rifle and a grudge against a chicken. I decided to salvage what was left of my dignity and go home, turning just in time to see a large whitetail doe not 50 feet away, studying me with large liquid eyes.

Seeing a deer was nothing new—you couldn’t go get a gallon of milk from the store without dodging at least one deer on the way. What was unusual was seeing one so close, and on the first day of deer hunting season, just a few days after my husband had casually mentioned he was thinking of getting a deer for the freezer.

I briefly considered going back inside, telling my husband where the deer was, and giving him the rifle to do the rest. But I was the one in the woods with a gun and a deer—what did I need him for? Besides, I was the better shot. Still, I hesitated: Was it legal? I knew my way around a rifle pretty well, I was on my own land, and it was the first day of deer season. Could I process a deer? I had processed a few turkeys and chickens before; how much harder could this be?

But there was still the question of pulling the trigger and ending a wild animal’s life. Could I do that? It wasn’t like we needed the meat to avoid going hungry. After all, I had a freezer full of meat.

Then I thought about the meat in our freezer: the factory-farmed chicken and mass-produced pork, the confined feeding operation (CFO) beef. I’d seen what went on inside factory farms, and the slaughtering wasn’t the worst of it. Surely harvesting my own venison was a more humane way of bringing home the bacon than anything currently sitting in my freezer. I lined up the sight just behind the foreleg as the deer stepped forward, and then I squeezed the trigger.

On My Terms

I did not grow up hunting. In fact, our whole family were avid anti-hunters growing up, mainly because most of the hunters we knew were poor examples of hunting sportsmanship, stewardship, and safety. Playing in the woods in the weeks leading up to opening day, my little brother and I regularly stumbled across illegal tree stands and piles of bait corn on our back acreage, put there by our neighbors without permission. As the season wore on, we’d find deer carcasses in creek bottoms with the head and backstrap missing, the rest left to rot. When the season was in full swing, we were forbidden to go into the woods at all except on Sunday (when hunting wasn’t allowed), but even then we had to wear blaze orange to ensure we weren’t mistaken for prey by a neighbor under the joint influences of booze and buck fever.

The hunters I knew as a child were reckless tough-guy types who saw each deer killed as a measure of their manhood. They spoke of hunting in tones reeking of locker-room brag sessions. From the boys in the back of the bus to the deacons after church, hunting talk was always the same: loud, coarse, and exclusively male. There was no place for someone like me in a place like that—whether I wanted in or not.

Then in mid-life, my husband and I moved with our young daughter back onto his family’s farm complete with fields, forests, a creek, and a lake. I’d long wanted to pursue greater self-sufficiency with our food, and now I had the chance. I started reading magazines about farming and food independence and got to work.

I raised a flock of laying hens and successfully took a few turkeys from farm to table. I gardened and raised honeybees and started an orchard and blackberry patch. Each new endeavor fed my confidence, and I realized that the biggest obstacle to my ambitions was my own ideas about where I did and didn’t belong. I’d come up in a world where knowledge of farm and forest, waters, and woods was handed down as a legacy. I had no such inheritance, but here I was, carving out my own little farm life on my own terms. Perhaps I could do the same with hunting.

And so it was that I came to be standing in the woods on a November morning, squeezing the trigger in a moment that changed everything.

Hooked and Humbled

The rifle snapped and the deer leapt back a few feet before taking off at a run, downhill toward the creek bottom. But it never made it. After just a few dozen yards, it slumped to the ground, breathed hard for a few minutes, and then went still.

I waited a few more moments before approaching the dead deer. When I finally did, a wave of conflicting emotions flooded over me—shame, pride, sorrow, and gratitude, but more than anything, a deep sense of responsibility. I’d never before come face to face with the cost of my own life, not even when processing the turkeys I’d raised.

This was different somehow, glaring proof that my life was bound up not just with the animals and plants my species raised in little plots, housed in barns, and bought in stores, but the whole of the natural world. Here at my feet lay the acorns and blackberry leaves and creek water of three years, the sunshine and snow, the mushrooms and mosses, even the very air—all made flesh. Here it lay now, for the good of me and mine.

The enormity of the realization shook me. Surely those hunters from my childhood had never felt this. If they had, they never could have talked like they did. Or maybe they had, and it had scared them, and that’s why they had talked that way in the first place. Wild things aren’t the only masters of camouflage.

It took me all afternoon to process that first deer, even with a book and YouTube videos, but in the end, I was able to proudly place 30 pounds of fresh, local, organic meat in my family’s freezer. I was hooked and humbled, not on the conquest or the adrenaline, but on the perfect synchronicity of it all.

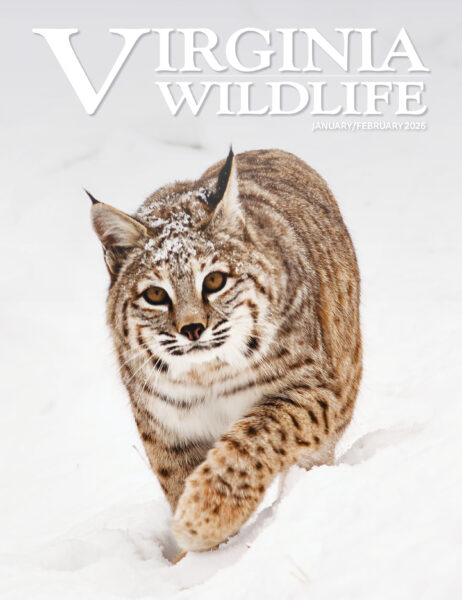

Hunting has helped strengthen Shannon Brooks’ relationship with nature and feed her family. Photo courtesy of Shannon Brooks

Watch the World Wake Up

Hunting means knowing on a very intimate level the price of your own existence. I’ve harvested dozens of deer in the two decades since that November morning, and I never take one that I don’t shed a few tears afterward. I’ve never lost a shot deer that I didn’t go down on my knees begging forgiveness. Harvest your own meat and you’ll agonize over every wasted morsel.

Hunting has also connected me with those around me, both inside and outside the hunting community. I find myself talking about deer sign with neighbors at the mailbox or sharing a soda with other camo-clad hunters at the local market. There’s no bragging in these moments, just a deep appreciation for these creatures and the chance to spend a few hours on their terms in their world.

It hasn’t been easy. Taking up hunting in middle age has meant a steep learning curve with plenty of mistakes, but I’ve made steady progress, too. I now know that wounded deer run downhill to water, except the ones that don’t. The biggest deer hang out in the thickest thickets, but so do bears. If you shoot a deer at dusk, you’ll have to trail it

by moonlight. Squirrels do an excellent impression of a deer walking through woods. Ticks and chiggers respect no boundaries. Always, always have more water than you think you’ll need.

Then there are the other lessons hunting has taught me, like hunting blinds on rainy days are made for napping, or that nothing beats being showered with golden poplar leaves in a tree stand. Sit in a tree stand and the world will show you how it wakes up each morning. You’ll see the earth take its first breath of the day, a sigh that comes just after sunrise and lifts the leaves oh-so-slightly like a sleeper turning over for five more minutes.

They say grace is being given what we can never deserve, and it’s hard for me to think of a more grace-filled moment than being in the woods on a fall morning, watching and waiting. There’s so much more to hunting than “bagging” something. There’s peace and beauty, and if you’re even luckier than you already are to find yourself in the woods on a fall morning, maybe you’ll see a deer too. You’ll squeeze the trigger and come to know a moment that brings you deeply and irreversibly into the grace of the whole wild world, and find that there’s a place in it for you, too.

Shannon Brooks is a teacher in Franklin County who enjoys fishing, hunting, and getting her hands dirty in the garden and orchard.

Five Tips for Getting Started Hunting

- Choose bolt over bullet. For beginning hunting, it’s hard to beat a crossbow. They’ve got all the accuracy and power of a rifle without the noise and recoil. Crossbow bolts (i.e. arrows)

are infinitely reusable and cheaper than bullets, making it less expensive to practice and sight in for pre-season prep. - Do your homework! There are TONS of books, magazines, videos, and digital content on all aspects of hunting. Dive in! Hear a term you’re not familiar with? Got a specific question? Google it (e.g. What is “brushing in”? How do I trail a wounded deer?). Check out DWR’s Help for New Hunters webpage.

- Start on the ground floor. Skip the tree stand for now and purchase a pop-up ground blind instead. They’re easy to put up, safe, comfortable, and dry. Add scent control spray and prepare for close deer encounters. Be sure to install the blind a month or so before the season starts to give deer time to acclimate to its presence.

- Go low-tech. Don’t have a four-wheeler to drag out your deer? Me neither. I use a wheelbarrow, garden cart, plastic snowsled, or tarp and rope. A come-along works well too in steep terrain.

- Use a deer processor. They are trained and inspected and get you the maximum amount of meat with minimum waste, all safely processed and neatly packaged. You can select your cuts and preferences and the cost is very reasonable, especially once labor is factored in. Just field dress your deer and drop it off. Need a list of processors in your area? Contact Hunters for the Hungry.

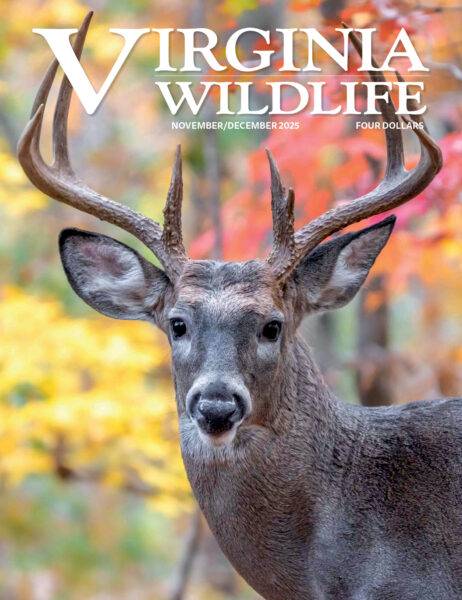

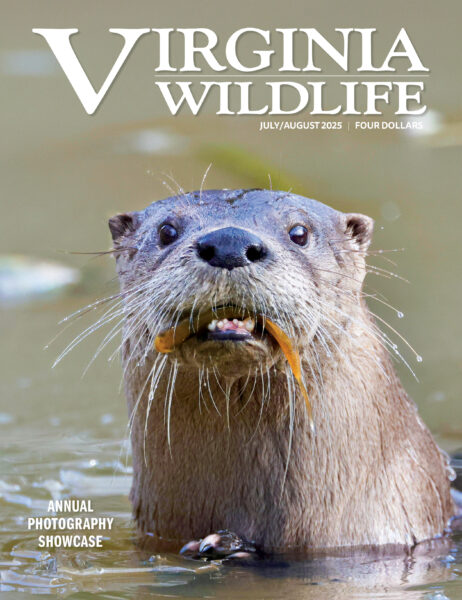

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe