Virginia's elk restoration is a resounding success.

By Ron Messina/DWR

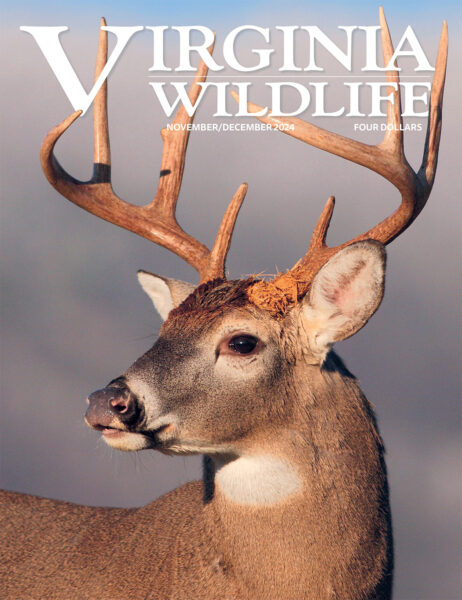

The big bull emerges from heavy fog into the blood-orange glow of sunrise. This is no ordinary elk, but the half-ton, undisputed King of the Mountain.

With his gigantic crown of antlers aglow in the light, this “8×10”—eight tines on one side, 10 on the other—stands nearly nine feet tall. He flicks the massive headgear, easily stripping branches from a small tree, while his stately harem of cows wanders into view behind, impressive themselves, with their large brown eyes fixed on the intruder photographing them and every breath visible in the morning chill.

A sudden piercing scream rises from the big bull, echoing across the hills, raising the hairs on the back of my neck. The loud bugle alerts to all, “I am here!” and warns competitors to stay away from this territory or be ready to fight. Far away on another mountaintop, a rival bull answers with his own call that is reminiscent of a flute, and then another bugle sounds on a ridge even more distant. It’s a lovely wild scene, one that you might expect to play out in the mountains of some remote western state. But this is Virginia.

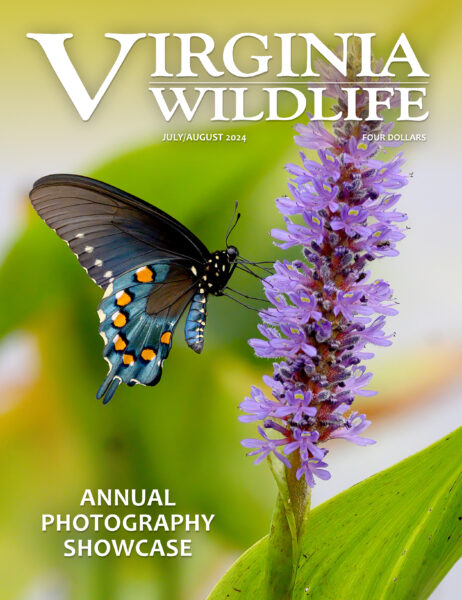

After more than 150 years, wild elk are back. And so is the thrilling opportunity to experience them in their natural habitat, right here in the commonwealth. They roam free in the Appalachian Plateau of rugged Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties, which share the state line with Kentucky. Often, large groups of elk can be found near a viewing area at the Warfork elk restoration site in Grundy, where sunrises and sunsets over the high elevation ridges are mind-blowingly brilliant. The return of elk to this unique place is fitting, not just because of the beautiful setting. Their presence tells the story of a scarred landscape restored, a rural mining community rejuvenated, and a lost species redeemed.

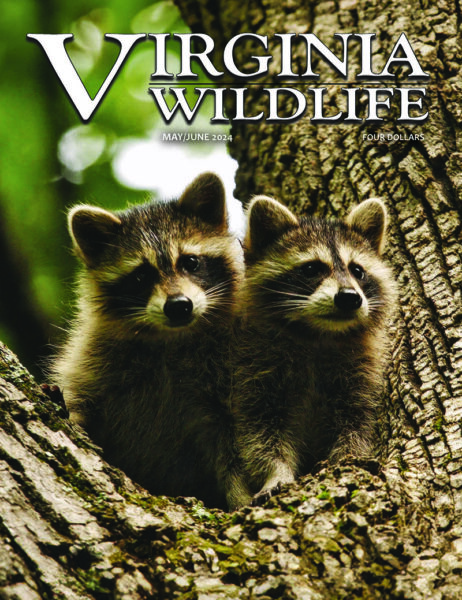

“It’s such a blessing to have elk back in Virginia and getting to see elk back on the landscape where they once were,” said Leon Boyd, a lifelong resident of Grundy, in Buchanan County. “I don’t think very many folks get a chance to do that in their lifetime, reintroduce an animal back to its natural habitat.”

Local landowner and conservationist Leon Boyd has played a pivotal role in the elk’s return to Virginia. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

The convergence of people, events, and good fortune that aligned to bring elk to Virginia has Boyd directly in the center; he grew up just a few miles away on his family’s mountain homestead and works at the drilling company that mined coal and drilled for natural gas here—on the very same mountain that now provides a sanctuary for the elk and many other wildlife species. He’s also a member of the Southwest Virginia Sportsmen, a local organization that partners with local landowners to improve elk habitat. And, he sits on the Board of Directors of the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), the agency that brought elk back to Virginia and manages the herd.

Boyd was one of the first to see the potential for the return of elk to transform this southwestern Virginia community.

He’d hunted elk out west and was admittedly “focused on hunting” when it came to the restoration project, until one afternoon when he agreed to take a man and his wife to the mountaintop to view them. Boyd noticed the man was slow to get out of the car; later he found out the man was battling pancreatic cancer, with a terminal diagnosis, and had a bucket-list desire to see and hear elk before he passed.

Just before dark, a group of elk appeared, and as they sat and watched them in silence, Boyd noticed a big smile on the man’s face. A sense of calm had come over the couple. “That’s when I knew it was more than just about hunting,” he said. “Wildlife can do that.”

But all the interest in viewing elk surprised even him. “From the tourism side, I felt early on we could draw folks here. But I don’t think even I understood the numbers of people we would see in such a short period of time that travel here to view elk,” Boyd remarked.

Virginia’s elk inhabit some of the most scenic, and also most remote, land in Virginia. But the out-of-the-way location is not a deterrent for wildlife watchers like Heather Pilgrim, who drove six hours from Colonial Beach to see them. “I didn’t think Virginia had the ability to have a herd of animals that large—I just had to see it!” she said.

Reclaimed mining sites make up much of the elk herd’s range. Photo by Ron Messina/DWR

Doug Goodman made the trip along with a tour group, hoping to see and hear a bull elk bugling at sunset. “Magnificent is the only word that comes to mind—what a beautiful place,” he said. “It’s just about the farthest point in Virginia that you could get from the capital in Richmond where I’m from, but it’s worth it!”

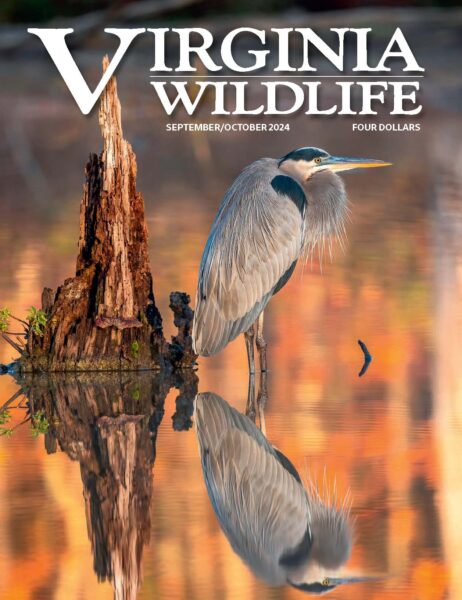

The high-country Elk Viewing Area in Grundy, located near the Southern Gap Visitor’s Center, is one of the best places for tourists to view them mornings and evenings, grazing in rugged fields. The most popular time of the year to visit is during “mating season” in September through early November, when it’s a sure bet bulls will be bugling and most active, and in the summer just after “calving season” when elk tours resume in July.

The Return of a Native

Just like the American bison, the grey wolf, and the mountain lion, elk (Cervus canadensis) were native to Virginia, but just like the others, they were extirpated by colonial settlers pushing westward. Elk were so plentiful in this country’s early days that during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Meriwether Lewis wrote, “They are common to every part of this country, as well as the timbered lands as the plains, but they are much more abundant in the former than the latter.”

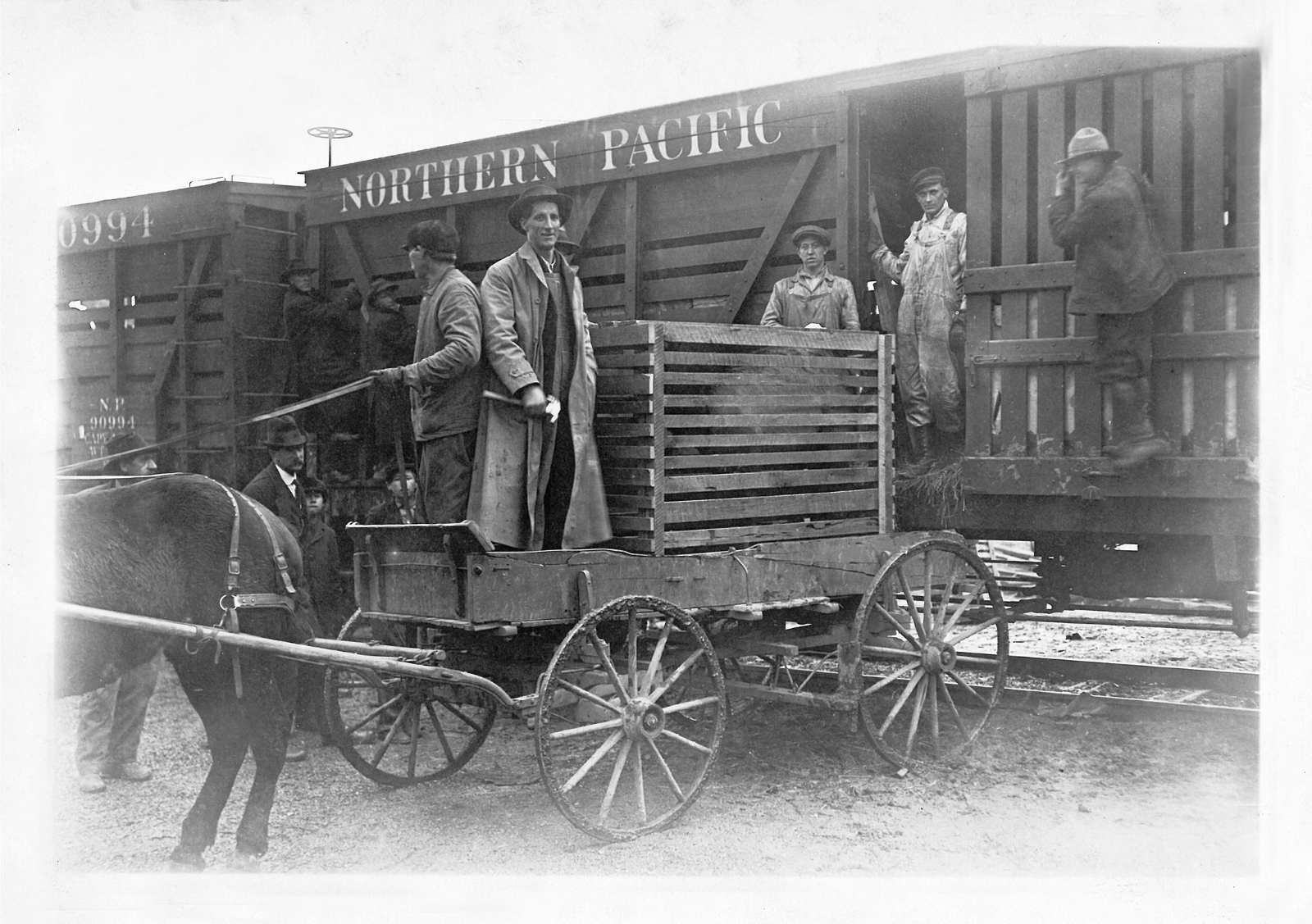

But in an era of unregulated market hunting, their numbers declined. In 1855, a hunter killed the last native Virginia elk in Clarke County. Over the years, various attempts were made to restore elk to Virginia. In 1917—just a year after Virginia’s wildlife agency, now DWR, was founded—officials brought in 125 elk from Yellowstone National Park to 11 counties, including to Princess Anne County in Virginia Beach, ironically one of the few areas in Virginia where native elk never existed, and where the lack of wild habitat would lead them to raid residents’ vegetable gardens. The poor site selections ultimately led to their demise and elk were once again absent from Virginia’s landscapes by 1970.

Elk brought to Virginia from Yellowstone National Park in 1917 arrived by railroad. Photo from DWR archives

“These efforts started before the field of wildlife management became a profession. They didn’t know what a good restoration effort would look like, or even the basic wildlife habitat requirements of elk,” says DWR’s Elk Project Leader, Jackie Rosenberger.

Kentucky’s elk restoration was in full swing when the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF and now DWR), the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and others began once again exploring the idea of bringing elk back to Virginia. Virginia Tech researcher

Dr. James Parkhurst was enlisted to conduct a feasibility study identifying suitable locations in Virginia to put a wild elk herd. The study was published in 2000 and an Elk Management Plan was developed, but the project stalled out until a decade later, when the DGIF Board of Directors voted unanimously to bring elk back to Virginia.

The restoration began on May 23, 2012, when DGIF employees released 20 elk—11 bulls, five cows, and four calves—that had been acquired from Kentucky’s herd. Additional elk were released in following years, totaling 75 animals.

Biologists ensured the health of the Kentucky elk that were released onto Virginia land in 2012. Photo by John Brunjes Photography

Today, they number “250 plus—with an emphasis on the plus,” according to Rosenberger, with two distinct herds roaming free in Buchanan County, another in Wise County, and a smattering of elk in other southwestern Virginia counties.

“We had this dream,” said Danny Smedley, the Virginia Chairman of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF) standing at a scenic overlook in Grundy, remembering that day he witnessed the first elk run out of the chute and into its new home. “There were some people who had a lot of hesitation about it, but after 10 years, they see that they’re here, they’re surviving, and people are enjoying them.”

Smedley says the elk’s return to Virginia represents more than just a wildlife success story.

“Elk need open spaces and wild places; elk need room to roam. To me, this animal represents that wilderness, those wild spaces,” said Smedley. “If we’re able to keep this animal around and the habitat it needs, it also preserves that for humans to enjoy not only the elk, but also the quietness and the opportunity to see nature in its full glory.”

A cow and calf from the restored elk herd. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

Appalachia’s Greatest Conservation Success Story

In this part of southwest Virginia, the country accent is thick, houses cling to the sides of hills, and the local Wal-Mart in Grundy, the one with two levels and an elevator, might be your best bet for finding an evening snack because it’s the only place still open. Mining pays the bills in this hardworking, hard-scrabble place—widely known for the high-quality bituminous coal extracted here—but elk tourism may be a big part of its future. The area’s mine reclamation sites, former strip mines, and mountaintop removals that were restored with topsoil can be converted to fields of grass.

Repurposing mining sites into elk habitat put conservation and coal mining into the same sentence. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

“Elk have a component of grasses in their diet at all times of the year,” explained Rosenberger, noting that this early successional habitat loaded with lush vegetation is crucial to their survival. “Historically, when you think of what the eastern U.S. would’ve looked like, a lot of our lands weren’t forested—they were open, they were grasslands and oak savannas. Elk, as well as bison, played a role in keeping those areas open, keeping that vegetation down.”

Wildlife-watcher Pilgrim was pleasantly surprised by the use of restored mining land to house the herd, and quipped, “No one puts coal mining and conservation in the same sentence.”

The unusual juxtaposition appears to be working. The only sign of mining operations still visible at the viewing area are the occasional natural gas well-heads, set along the gravel roads now traveled by elk tour buses, which are managed by Breaks Interstate Park.

Austin Bradley, the park superintendent, said “the popularity of the tours surged in 2019 and set attendance records” the last two years. Frequently the tours are sold out in advance, with many visitors traveling for more than four hours just to see the elk.

As popular as the elk are with the rest of Virginia, it’s the local residents that have become most smitten with them. Buchanan County brands itself as “The Elk Capital of Virginia” and features an elk on its new “Embrace the Wild” logo.

“I think it’s been amazing to see what it’s done for this community,” said Smedley. “You take a rural Appalachian community and give it hope and new life, and see a new community center, and visitor’s center. They’ve adopted the elk with open arms.”

The Southern Gap Visitor’s Center has become a community focal point. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

The new Southern Gap Visitor’s Center is located in the heart of Buchanan County’s thriving outdoor recreation area. It sits alongside a large RV campground, Southern Gap Outdoor Adventure, as well as the trailhead for Spearhead Trail’s Coal Canyon Trail, which links 220 miles of ATV trails with hiking, biking, and bird-watching opportunities. The spacious visitor’s center serves as a community focal point for weddings and parties. Elk are often visible, roaming in the fields nearby.

Owner Billie Campbell, wearing an Elk Fest polo shirt and standing beside a full-body mounted elk in the visitor’s center, says the herd growth over the last five years has been “tremendous.” Campbell says it gets “really exciting” in the fall, when bulls fight and bugle.

“And when it gets exciting we have people coming from everywhere. We’ve had visitors from all 50 states and six countries come and spend the night here,” said Campbell. “There are all kinds of trails in the country to ride. But there aren’t a lot of trails you can go ride and come up on a momma elk cow with a calf, or two bulls fighting in the field.”

The Visitor’s Center hosts “Elk Fest” each October, a celebration of mountain culture, with plenty of arts, crafts, music, food vendors, and highland games. “If the elk weren’t here, we wouldn’t be doing those things,” Campbell said.

The Adventure of a Lifetime

In 2022, Virginia’s elk restoration reached a major milestone—the elk herd had grown large enough to allow limited hunting opportunities. DWR sponsored a lottery elk hunt, in which five hunters were drawn and eligible for an elk tag, and authorized a partner organization, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, to host a separate lottery for one additional hunter and tag. The six hunters all met with success, with one hunter from New Mexico taking a massive Boone and Crockett Club Virginia State Big Game Record bull that scored 413 ⅞ inches for non-typical American elk.

“It was the adventure of a lifetime,” said one of the elk hunters, Bob Painter of Unionville, who enlisted his son and grandson along on the hunt to call and act as spotter, respectively. Painter harvested a 7×7 elk. “It was the greatest thing that ever happened to us,” he said, grinning. The other hunters all echoed this sentiment, with many expressing appreciation for the assistance of DWR staff, Boyd, and the Southwest Virginia Sportsmen, who swooped in to assist them after the harvest.

Virginia’s 2022 elk hunt was successful thanks to the collaboration between DWR< landowners, volunteers, the Southwest Virginia Sportsmen, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and hunters. Photo by Mike Roberts

The first lottery hunt enticed 31,951 sportsmen to apply, raising more than $500,000 for DWR programs, a great boost for an agency that’s almost entirely funded by hunting and fishing license and boat registration sales.

“Our goal was to someday have a huntable population, and we have reached that,” Rosenberger said. “It’s important to note that this hunt is not about population control at all—we have plenty of room to grow our elk population within our elk management zone. This hunt is more about that fact that we’ve reached an abundance level with our elk population that we can allow some amazing recreational opportunities for hunters to go after these bulls in October without having negative effects on our population growth. This perfectly aligns with our mission as an agency to further recreation through hunting, as well as a goal of putting elk on the landscape in the first place.”

The Road Ahead

Now that elk are decidedly back on the landscape, there are new challenges on the horizon. The bulk of the elk herd resides entirely on private properties at the moment. Even the original elk release site is owned by The Nature Conservancy, a private conservation organization that partners with DWR. Similarly, all the property owners where the elk roam have worked together to protect the elk while providing public viewing and hunting opportunities. But pressure is mounting to have some elk on public lands.

“We have several different teams working on land acquisition and access, as well as habitat plans,” said Tom Hampton, the DWR lands and access coordinator in Southwest Virginia.

Hampton, like Boyd, has seen the project through from its beginning, when he helped transport the first elk to Virginia. He said acquiring additional land is a top priority, and public access opportunities are growing through a network of habitat incentive programs, partnerships, and easements.

DWR Elk Project Leader Jackie Rosenberger (second from right) monitors elk movement and behavior with radio collars on some individuals. Danny Smedley, state chair of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (left) and area landowners assisted her with collaring this cow elk. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

Another possible challenge could involve a new highway that’s being built through the area, connecting Grundy, and Elk Horn City, Kentucky. The road may allow easier travel and more tourism opportunities, but elk are using the graded roadside as a travel corridor. Designated elk crossing signage and wildlife bridges or tunnels may be needed to keep both humans and elk safe. DWR staff has met with transportation officials to explore possible solutions, should they be needed. Despite all the tasks ahead, there have been few issues with the elk to this point, according to Hampton.

“The elk are able to win people quicker than we can win them,” Hampton said. “Even more of the community now are supporting it than in the beginning.”

One destination along the new highway will be Breaks Interstate Park, where Bradley said the elk restoration project is “Appalachia’s Greatest Conservation Success Story. The reintroduction of elk has given us an opportunity to correct a mistake and restore a majestic animal to its native range. When our guests hear this story on a fall trip during the rut, at the same time they are hearing the bugling of the bulls in the herd, it moves some of them to tears.”

Smedley added, “It’s something we can pass down to our kids and our grandkids. They’ll have this to look forward to. It’s exciting!”

Back up on the mountaintop, the unthinkable happened. The big 8×10 bull, the King of the Mountain, has been displaced. No one witnessed the fight, but the result is evident—he walks stiff-legged across a wide field, alone, away from his harem of cows.

It’s partly this drama and majesty of nature that draws people to the elk. It’s easy to get mesmerized by them, here on this wild, remote Appalachian mountaintop, with the colorful fall leaves, the mist in the morning and the magnificent sunsets at night. And the sounds—in the distance a trumpet-like bugle, signaling to all that there’s a New King on the Mountain.

Ron Messina is an avid outdoorsman who loves to write about his adventures in the field. He’s the Video Production manager at the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe