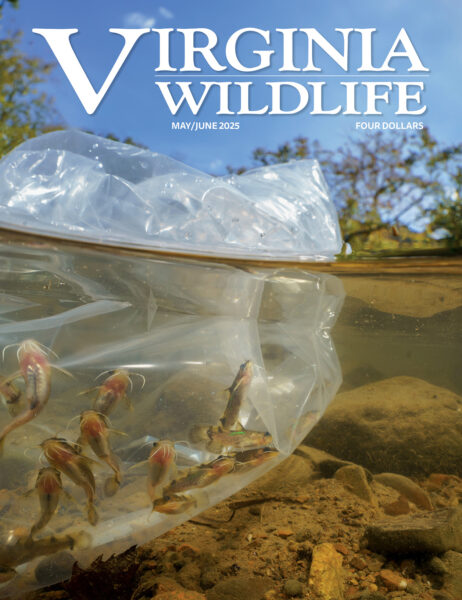

While Virginia’s charismatic state fish is facing some challenges, efforts are underway to help it thrive.

Brook trout: ©Patrick Clayton/Eric Engbretson Underwater Photography, Backgrounds: Shutterstock

By Molly Kirk/DWR

With its vivid coloring and status as the only native trout to Virginia and the state fish of Virginia, the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) is an iconic fish for the Commonwealth’s anglers. Brook trout have occupied Virginia’s high-elevation, cold-water streams since the glaciers receded in the last Ice Age more than 15,000 years ago. For many anglers, catching a wild brook trout from one of Virginia’s picturesque streams is an experience difficult to match.

But the brook trout’s very name reflects its vulnerability. “Fontinalis” means “of the springs,” revealing the species’ reliance on cool, clear water to survive. Brook trout prefer water temperatures below 65˚F. “Temperatures of about 70 degrees are going to be stressful or fatal to a brook trout, while they’d be ideal for a largemouth or smallmouth bass,” said Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) Chief of Fisheries Dr. Michael Bednarski. They also require well-oxygenated water of exceptional quality, a habitat of sand and gravel stream bottoms with minimal sedimentation, and waters shaded by vegetation and woody debris.

Unfortunately, trends of warming waters and increasingly intense precipitation events that result in dramatic water flows, erosion, and sedimentation threaten brook trout populations in Virginia.

“We have a variety of concerns about what’s going to impact brook trout,” said Bednarksi. “In addition to stream temperatures warming, there are also concerns about habitat conditions and degradation and a variety of other factors. It can be death by a thousand cuts. The difference between stress and lethal is a fine line. The fish can handle stressful temperatures at some level, but if you have other factors being put into place, it compounds and you can see sub-lethal effects even if the water isn’t at lethal levels of warmth.”

Brook trout occupy more than 614 individual streams over 2,000 miles of water in Virginia. In the Virginia Wild Trout Management Plan (2019-2028), DWR biologists note that DWR “has documented declines in occupied habitat on several streams and recognizes threats that may cause additional population declines. Therefore, the brook trout was listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2015 Virginia Wildlife Action Plan.” The Wildlife Action Plan identifies opportunities to maintain and improve natural habitats and conserve wildlife in response to 21st century challenges.

A 2013 study, “Virginia’s Climate Vulnerability Assessment” by Austin Kane of the National Wildlife Federation (NWF); Chris Burkett of the DWR; Scott Klopfer of the Conservation Management Institute, and Jacob Sewall, PhD, of Kutztown University, included one model that predicted the extirpation of brook trout from Virginia by the end of the 21st century.

“Both the lower and higher emissions scenarios indicate Virginia could become climatically unsuitable for brook trout by mid-century. This could result in the possible extirpation of this fish and other cold water species,” stated NWF’s study.

NWF’s study has a dramatic conclusion, but other scientists have conducted studies that resulted in different models and predictions. The bottom line is that there’s no crystal ball for knowing how Virginia’s brook trout populations might react or adapt to changing conditions. With that in mind, DWR fisheries staff is working with various other state and federal agencies and non-governmental organizations to understand the challenges that brook trout face and implement strategies to mitigate them.

“We really believe that the best strategies involve habitat restoration—stream shading, maintaining stream integrity, restoring fish passage—to help reduce the impact of increased thermal stress on those water bodies,” said Bednarski. “If we help keep them cooler, it will help to maintain brook trout populations.”

Knowledge is Power

In 2011, DWR biologists installed temperature-sensing data loggers in more than 50 wild trout streams from different physiographic regions, latitudes, elevations, and with different amounts of groundwater inputs, collecting hourly water temperature measurements.

The U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, United States Geological Survey, and Trout Unlimited are also collecting water temperature data from select wild trout streams in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest, Shenandoah National Park, and private lands.

Analysis of DWR’s data has begun. “We have 10 years of data to see if anything’s changed,” said Brad Fink, a DWR coldwater fisheries biologist. “We wanted to get a 10-year period before we analyze because you want to know the long-term trends.”

DWR also works with various partners to gather and share information about what’s going on in Virginia’s brook trout streams, including the Eastern Brook Trout Joint Venture (EBTJV), a network of experts who coordinate and fund regional brook trout research and habitat improvement projects.

“We work with a number of different groups, including the EBTJV,” said Fink. “There’s also the Southern Division of American Fisheries Society trout committee and a Chesapeake Bay Program Book Trout Action Team. We all share knowledge and data, what we’re working on, and sometimes we work jointly on projects across the region.”

Established in 2005 to improve fishable populations of wild brook trout, one of EBTJV’s most important products has been its assessment of brook trout from Georgia to Maine. “We work with states and federal agencies to know where brook trout are, from actual data from electroshocking or by using landscape variables to predict where brook trout would be,” said Lori Maloney, coordinator at EBTJV. “We are currently working on an update, so we can track losses and gains, and areas to protect.”

This distribution map can be used interactively with other habitat information to help the EBTJV and wildlife agencies make management decisions and use resources where they’ll have the most impact. “We look for patches or strongholds, or connected brook trout populations,” Maloney said. “One thing we are working to do is to layer this information with temperature data, so we can ask ‘Here’s a stronghold of brook trout that we want to protect, what’s going on with stream temperatures there?’ Or we can identify streams with cool groundwater flow that will really help the brook trout hold on. We’re looking to see how we can use that information to better manage the future for brook trout by helping direct federal and state dollars to projects that put brook trout back in streams, or remove barriers, or further improve stream habitat.”

To determine where brook trout are swimming in Virginia, DWR fisheries staff uses electrofishing, a method of shocking fish with a low-voltage current of electricity in a specific stretch of stream, then capturing the temporarily stunned fish.

Once they’re weighed and measured and the data recorded, the fish are released unharmed. Recently, DWR biologists have added another tool—environmental DNA, or eDNA (for more about eDNA, see “Environmental DNA is an Exciting New Tool for Biologists” in the September/October 2022 print edition).

“When we electrofish, we only do 100 or 200 meters of stream. We may not get everything. Whereas the eDNA picks up for a whole kilometer,” said Fink. “It’s one of those tools that we’re probably going to start rolling into our sampling protocol.”

Both electrofishing and eDNA will help DWR biologists determine which waters host brook trout, helping guide management decisions.

Riparian Remedies

It’s not just the temperature of the water that’s so important to brook trout; it’s also the quality of the water and the composition of the stream bed. According to DWR’s Wild Trout Management Plan, “Wild trout require ‘pea-sized’ gravel substrate free of fine sediments to reproduce. Sediment can also reduce habitat complexity vital for different life stages of wild trout. In addition, sedimentation can also negatively affect stream macroinvertebrate populations, which are a valuable food source for wild trout.”

Severe storms and heavy rain events, which are increasing in frequency, cause both the erosion of stream banks, sending a cascade of sedimentation into the water, and increased velocity of stream flows, which can disrupt fish spawning or displace eggs. Protection and restoration projects of stream and river banks (also known as riparian areas) can help reduce sedimentation in wild trout streams.

Riparian restoration and protection includes projects such as erosion and sediment control plans and permits, stream bank protection projects, exclusion of livestock from riparian areas, tree planting in riparian zones, construction of rain gardens, and stormwater retention structures, according to the Wild Trout Management Plan. There are multiple nongovernment organizations in Virginia working to help restore and maintain trout habitat, such as Trout Unlimited and the Piedmont Environmental Council.

Crooked Creek runs through DWR’s Crooked Creek Wildlife Management Area with more than 2 miles of native brook trout waters. This portion of the creek showed severe bank erosion. A DWR project restored the streambank, stabilizing the bank to prevent further erosion and enhance aquatic habitat. Photos by Louise Finger/DWR

DWR has also established Time of Year Restrictions (TOYR) for work conducted in or near wild trout streams to reduce sediment input to the stream when trout are engaged in spawning activity or eggs and sac fry are present. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Virginia Department of Transportation follow TOYR guidelines when working in or near wild trout waters.

Trees in riparian areas don’t just prevent erosion and sedimentation, they also provide essential shade to help keep the water cool, create cover and pools, and add leaf litter. “If the trees are there, insects are going to follow, and that’s food for brook trout,” said Maloney.

One tree species in particular that is important to trout streams in the region is the Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). The hemlock’s needles form a dense canopy that helps shade a stream or river even more than a hardwood tree. But an invasive insect, the woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) from East Asia, has been killing off hemlocks in the Mid-Atlantic region.

The woolly adeleid harms hemlock trees specifically, but poor land use practices—like agriculture and growth of development, or a history of clear-cutting—are much more common drivers of tree loss in riparian areas and resultant habitat losses for brook trout. Restoring that riparian vegetation can help expand brook trout habitat and range.

Livestock with access to streams can affect water quality by increasing sedimentation, disrupting the stream bed, and harming vegetation on the banks. Photo by Bruce Ingram

Maloney points to a project along Massanutten Mountain that EBTJV helped the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and other partners with on Smith Creek. In just 12 years, an intensely farmed stretch of the creek that had barren riparian areas was converted to an area with dense tree canopy and stabilized banks, resulting in much healthier habitat for brook trout and other species.

Make Way for Trout

Another strategy employed to help brook trout populations is fish passage projects. According to the Wild Trout Management Plan, “Wild trout require unimpeded mobility up and downstream and access to tributaries for spawning, locating low-flow and thermal refugia, and for maintaining genetic viability.” Things like dams, poorly-designed box and pipe culverts, and low-water hardened fords can obstruct the movement of brook trout.

DWR biologists, including Fink, recently received training from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to better assess fish passage at culverts and identify locations where passage can be improved. DWR works with organizations such as the North Atlantic Aquatic Connectivity Collaboration (NAACC), a network of organizations and agencies, to learn more about improving aquatic connectivity.

Fish passage is another area where organizations like EBTJV, Trout Unlimited, and the Piedmont Environmental Council work to provide guidance and funding for projects. Many trout streams are located on or border private properties, and the organizations assist landowners in replacing driveway or road culverts with solutions more amenable to fish passage.

“When you replace a culvert with a crossing that is sized appropriately to let water through without damaging the stream or roadway, you’re actually helping improve brook trout’s ability to find cooler water and suitable habitat, for not only foraging and living, but also for spawning and reproducing,” said Maloney. “It also helps with climate resilience for the connected human communities because the replaced crossings are much easier to maintain and much safer because they are much less likely to wash out during large storm events.”

Fish passage projects that replace barriers with fish-friendly solutions like this culvert expand the range of a variety of fish.

Once fish habitat has been restored, putting brook trout back into streams by relocating wild brook trout from other water bodies can help boost the populations. In 2017, DWR worked with Trout Unlimited and USFS to relocate 150 wild brook trout into Upper Passage Creek on the George Washington National Forest. DWR biologists are monitoring that population to see if natural reproduction occurs for multiple years. There are seven other streams where DWR has helped reintroduce or introduce wild brook trout and seen them establish native, reproducing populations.

What You Can Do

Everyone wants to see brook trout not only thrive as a native species, but also continue to be a prized sport fish for Virginia anglers. For anglers, fishing can be done with an effort to minimize the stress on brook trout. “Generally, we don’t see too much fishing pressure on brook trout in those streams in terms of catch-and-keep mortality, so we don’t see a need to put regulations in place,” said Bednarski. “If anglers want to go a step beyond, they could avoid fishing for brook trout during the summer or during the hottest hours of the day.”

Brook trout are a treasured resource for Virginia’s anglers as well as an integral part of the aquatic ecosystems, so preserving their habitat to keep them healthy into the future is important. Photo by Max Meveneau

The primary way citizens and anglers can help Virginia’s brook trout population—get involved in efforts to improve habitat. If you’ve got property along a stream, keep the riparian zone in good condition so that there’s shade on the water. Make sure the banks are intact to prevent sediment spreading.

If your property includes a barrier to fish passage, work with the state agency to identify funding sources to help you remove or replace it with a solution that allows fish to move beyond it.

“It will have benefits to you and the people who live around you as well as to brook trout,” said Maloney. “The entire aquatic community benefits from all the measures that improve habitat for brook trout, as it also improves water quality for people who live downstream.”

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe