In just 14 years, the golden eagle has gone from virtually unknown in Virginia to a species with a vast amount of data to inform future management decisions.

By Molly Kirk/DWR

Wildlife biologist Jeff Cooper distinctly remembers when his supervisor suggested studying golden eagles in the mountains of western Virginia. “I thought it would be a waste of time. I thought golden eagles were just vagrants that showed up occasionally in Virginia,” said Cooper, the non-game bird project coordinator for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR).

“There were guys at Clinch Mountain Wildlife Management Area [in Smyth County, Virginia] who had been reporting seeing these birds for years, just watching them. I thought they didn’t know what they were talking about, and they were misidentifying the species,” Cooper recalled. “But they were right!”

In the last months of 2009, Cooper set out some deer carcasses on high-elevation ridgelines in western Virginia and trained trail cameras on them. And lo and behold, images of golden eagles showed up on the trail cameras when he checked them.

“I was totally blown away. What I thought was true was that these birds were vagrants in Virginia, we weren’t getting involved in this project, and it was a waste of time,” Cooper recalled. “Fortunately, my boss, Ray Fernald, pushed me in a direction I didn’t want to go. And it turns out that golden eagles are a significant resource right here in Virginia and throughout the central Appalachian mountains.

“That’s the thing that was a little dumbfounding at the time, and still kind of is,” Cooper continued. “I could take you to Walker Mountain in Bath County, and you could literally catch an eagle a day on those baited sites, but we could sit up there for a week without the baited sites and never see an eagle on those mountaintops. They’re somewhat cryptic, because they’re in the woods, or they’re flying high above the ridgelines with obscured fields of view.”

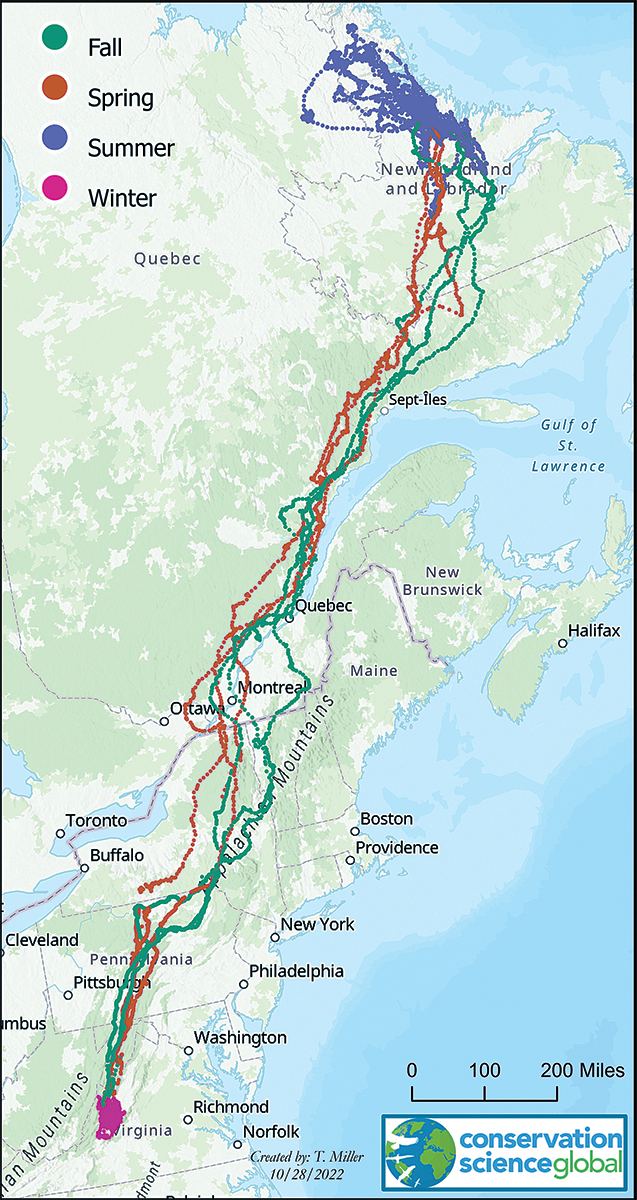

During the 2010s, Cooper and his team trapped dozens of golden eagles and outfitted them with GPS transmitters affixed to a backpack harness. The devices collected data on the location of individual birds at 15-minute intervals during the winter and summer months, and as frequently as every 30 seconds during migration in the spring and fall. The data gets transferred over the cell phone network and back to biologists, who can then calculate the size of individual winter home ranges and breeding territories and characterize habitat use patterns.

Jeff Cooper holds golden eagle equipped with a transmitter before releasing it in the cold mountains of Highland County. Photo by Jeff Cooper/DWR

The birds trapped and equipped with transmitters in Virginia provided a significant amount of data that not only shed light on the species’ behavior, but also is shaping management decisions about the species. Blood samples taken from captured golden eagles were also essential for a study on lead poisoning in the U.S. eagle population.

Uncovering the Patterns

Cooper wasn’t alone in not knowing much about the golden eagle in Virginia in 2009. Golden eagles are a well-known, much-studied, and somewhat abundant species in western North America, from Alaska south to Central Mexico. However, prior to the work started in Virginia, not much was known about the species east of the Mississippi.

Thanks to the efforts of Cooper and other biologists and wildlife managers that are part of the Eastern Golden Eagle Working Group (EGEWG), data now exist of the smaller, geographically isolated, and potentially distinct population that breeds in northeastern Canada. These birds migrate through the central Appalachians of New York and Pennsylvania to winter in Virginia, West Virginia, and neighboring states. Its winter range in Virginia is primarily associated with the Appalachians, although some birds may also be found in the Coastal Plain and records exist for the Piedmont.

Cooper and his team trapped and attached transmitters to more than 35 golden eagles between 2009 and 2013—about a third of all the birds captured for the EGEWG’s data collection. “Jeff contributed a big sample size to our data set,” said Tricia Miller, Ph.D., executive director and senior research wildlife biologist at Conservation Science Global and part of the EGEWG. “The information gained has been incredible, because what was known about golden eagles even in 2009 was limited. Getting the telemetry data showed us how these birds were behaving, the places they were living, where they were flying—things that were basically unknown about the wintering population.”

Golden eagles are very hard to spot while they’re wintering in forested mountain areas. Photo by Michael Lanzone

Golden eagles wintering in the west of North America use open and semi-open habitat to primarily hunt mammalian prey. But the eastern population that winters in the Appalachian Mountains behaves quite differently. “These birds are incredibly difficult to see, especially during winter,” Miller said. “You can go to any ridge or mountaintop in late October through November, and you can see them migrating, but once they’re in their wintering grounds, they tend to be out of sight because they’re often in forested, high-elevation areas that are generally far from people, especially during winter. The data collected in Virginia were very helpful to inform about their range and behavior while wintering.”

Cold and With Talons

It’s a daunting task to capture a golden eagle. The species is one of the largest birds in North America, with a typical wingspan of 6 to 7 feet, and fearsome talons. Cooper and his team were attempting to do so in bitter cold and at isolated, high-elevation sites. “The elements and the mountains are their own challenge. It was cold!” Cooper said. “One winter in Highland County, there was 2 ½ feet of snow with a high of 5 degrees.” There’s no way to sleep comfortably in a hotel room and be on the snowy mountaintop at dawn to trap an eagle, so Cooper and those helping him would camp and sleep on the mountain for days at a time. They’d drive as far as they could, then take a four-wheeler to the camp site.

Golden eagles are skittish and wary, so Cooper would have to set up the bait (a road-killed deer carcass) and the trapping equipment with a trail camera monitoring it first. Once he saw regular golden eagle visits to the site happening on the camera, they’d place a portable deer blind about 20 yards away, sneak into it before sunrise, get into sleeping bags for warmth, and wait for the birds. “Sometimes it would be just like clockwork and easy, and they’d just come in and you could catch them,” Cooper said. “Then there were times we waited for days and nothing came.”

A trailcam photograph of a golden eagle at the Walker Mountain National Forest.

Cooper and his team used rocket nets to trap the golden eagles, a 60′ by 40′ net that’s folded accordion-style and laid on the ground. Three rockets with small explosive charges were attached to the net, with blasting wire that ran to the deer blind. The team would place the deer carcass and netting strategically. “Golden eagles like to feed standing on the animal, so when we prepared the bait, we’d open up the backstrap and have it facing the net, so the eagle was forced to have his head down facing the net,” Cooper recalled. “We’d let them feed for a bit, and when their head was down, we’d detonate the rockets, which would carry the net over the bird. On a few occasions, they were quick enough to fly out of the net, but in most cases, they weren’t.”

Golden eagle talons are sharp and powerful, so DWR staff capturing the birds had to take care to protect themselves and the eagles. Photo by Jeff Cooper/DWR

The team would have to work quickly and carefully while handling the birds. “The defensive posture of an eagle is to flop over on their back and try and attack you with their feet. Their feet are so powerful and they try to grab you, so it usually takes a couple of people to get their feet untangled and under control,” Cooper said. “We put a hood on the animal and gave the eagle a ball of [adhesive bandage] to grip with its feet so it didn’t injure itself with its talons. We’d wrap the feet up so we didn’t get injured.

“Then we’d go through the banding process with a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) bird banding lab band. We took blood samples for lead and genetic analyses and to genetically sex the bird. We would take our measurements, then we would outfit the animal with a transmitter on its back, attached with a Teflon strap that we would put across its breast and under its wings, like a backpack. That takes a couple of people to do. Then we’d take the protective equipment off and let the bird go. It was a tremendous amount of work. Actually catching the bird was the easy part, but all the logistics and equipment and gear was complicated,” Cooper recalled.

Cooper makes sure to credit the immense amount of support he had for the project from the DWR Lands and Access staff, DWR district biologists, the U.S. Forest Service, and supervisory and administrative staff at DWR. Cooper is also appreciative of the guidance, mentorship, and hard work of Miller, Todd Katzner, Mike Lanzone, and Dave Kramar, Ph.D, on the project. “The most satisfying part professionally was this data set, but also the personal relationships I developed both within and outside the agency,” he said. “It was humbling to see how talented and smart all these people in DWR and our partners are.”

Using the Data Creatively

Once the eagles Cooper and his team had captured were back flying with their active transmitters, the data began pouring into the EGEWG, along with that from eagles trapped in other states. “It is a comprehensive set of data. Because of the work done, including by Jeff, we’ve been able to figure out how the eastern golden eagle population uses and moves through eastern North America,” said Katzner, Ph.D., a USGS wildlife biologist and part of the EGEWG.

This map shows the movements of an adult golden eagle captured and released by Jeff Cooper at Shilling Access Trail on February 22, 2012. Her transmitter was active until January 2015. The map reveals her wintering range in the Highland County area, migration paths, and her summer range in Labrador.

“There wasn’t a whole lot known about this population, especially their broad spatial movements, before the project got going,” Katzner said. Now biologists can track eastern golden eagles’ movements from breeding grounds in northeastern Canada, along their migration through the central Appalachians of New York and Pennsylvania, and to their wintering in Virginia, West Virginia, and neighboring states.

The data set allows analysts to study the golden eagles’ habitat and resource selection, their migration routes, how weather influences them, and what areas they’re choosing to winter in. “It’s limitless what can be done with the data we’ve collected. These data will be useful for a long time; what we get out of it depends on how creative you get with it,” Miller said.

Cooper noted that the data collected from the eagles shows their movement three-dimensionally. “That’s important because some of the major management questions we had were some of the potential impacts of wind energy on these birds. At the time, there weren’t any operational wind farms, so it was one of those rare opportunities where we were able to gather data before there was a management challenge, which was wind energy,” he said.

Miller is currently using the golden eagle telemetry data for a model that will create a heat map of high-, medium-, and low-use eagle areas across their range in Virginia. The footprint of wind energy facilities can be overlaid on the model to estimate if the eagles would potentially be impacted by the wind turbines in the facility.

The blood samples collected from Virginia’s golden eagles were also used in research by Vincent Slabe and others that resulted in a paper published in Science in February 2022, “Demographic implications of lead poisoning for eagles across North America.” The study found unexpectedly high levels of lead in almost half the golden and bald eagles studied. “The national focus on the issue became huge because of that paper,” said Katzner.

“There have been many peer-reviewed publications as a result of that initial golden eagle work we started in 2009,” Cooper said. “It’s been such a team effort with academics, non-government organizations, and federal partners.” While the trapping phase of the project is mostly complete, the EGEWG is still very active, working on a golden eagle conservation and management plan both within the United States and in Canada.

“We have this very powerful database that can be used to influence management,” Cooper said. “Now the next challenge is synthesizing and analyzing the data, creating these models, and then actually getting the decision-makers to utilize them.”

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

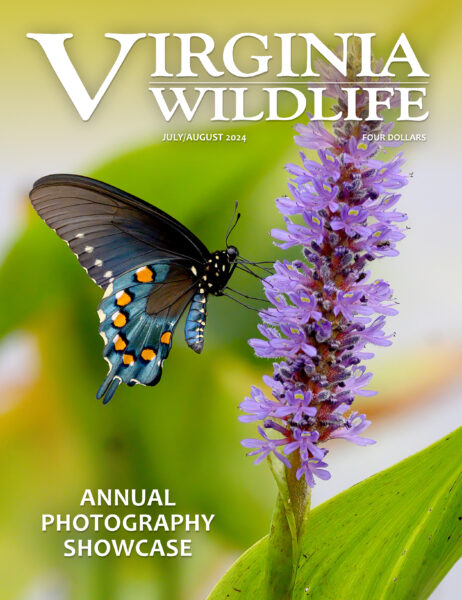

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe