By John Page Williams

Photos by John Page Williams

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR’s) Lawnes Creek Landing has a new two-lane launch ramp with aluminum dock and fishing pier. It’s an excellent jumping-off spot to explore the lower James River and Lawnes Creek itself. The landing actually lies within the Carlisle Tract of DWR’s 3,908-acre Hog Island Wildlife Management Area at the lower end of Surry County, with the WMA’s Stewart Tract on the other side of the creek in Isle of Wight County. Whether you’re interested in fish, birds, or history, this area is well worth exploring by skiff or paddlecraft. A friend and I recently launched my skiff on a blustery day and ran first outside into the James before returning to explore up the creek.

The fishing pier at Lawnes Creek Boating Access Site.

Lawnes Creek was the upper territorial boundary of the Warraskoyack Tribe at the time of Jamestown’s founding in 1607, though their chief lived downstream on the river named for the tribe (today’s Pagan River). The Warraskoyack people had been here for at least several centuries. They must have found it a rich area, with oysters, clams, and blue crabs out front in the James; sturgeon and rockfish in nearby Burwells Bay; herring, stiffback (white) perch, and ring (yellow) perch up the creek; woods for hunting deer and turkeys; wild rice, tuckahoe, and cattail marshes in the creek for foraging; fertile soils for growing corn, beans, and squash; and the big river for travel. Early colonists described them as friendly, and they gladly traded corn for English goods.

Quickly, though, English colonists took over this area. Capt. Christopher Lawne, a stockholder in the Virginia Company, came to Virginia in the spring of 1619 with a crew of men to establish a plantation patented on the neck of land between the creek that would bear his name and the James River fronting Burwell’s Bay. At the beginning of August, he and one of his men served as the Burgesses for his plantation at Jamestown’s historic first General Assembly. It had been, however, a difficult summer, especially for disease. Lawne and his men had to abandon the plantation in the fall and move upriver to Jamestown, where he sickened and died in November. Two years later, though, other Virginia Company stockholders re-established Lawne’s patent and several others in Warraskoyack territory, extending from what they by then were calling Lawnes Creek down past the Warraskoyack (now Pagan) River to the territory of the Nansemond Nation. Because the leaders of this group came from the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, they gave this new county the same name, which it still holds to this day.

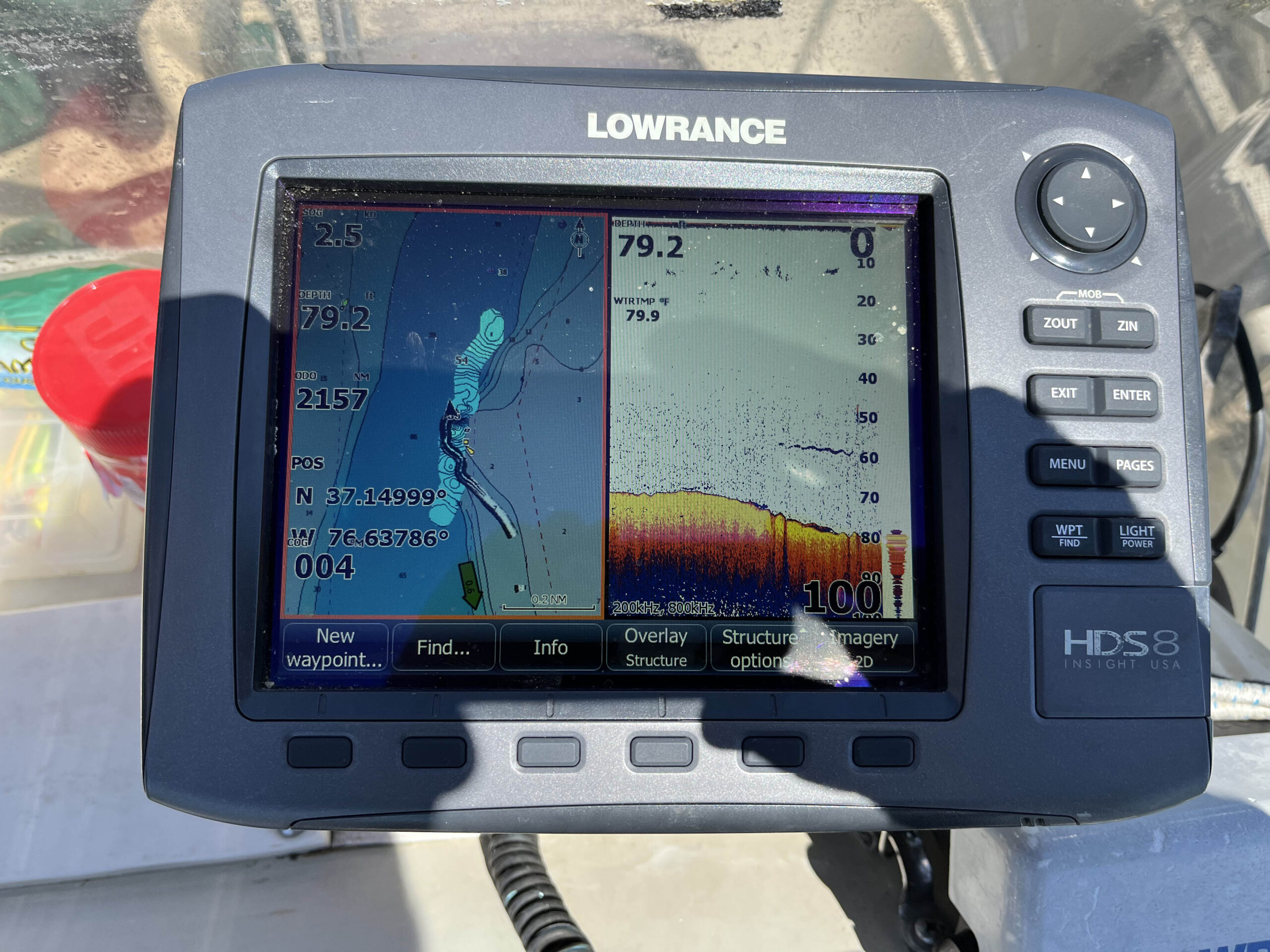

Just outside Lawnes Creek’s mouth, the James River off Hog Island and Isle of Wight County shows off its power by gouging out an 86-feet-deep hole just off the flashing red marker at Deep Water Shoals. Even though the river is 3 ½ miles wide here, the channel is quite narrow, with shallow shoals on each side. All of the flow from the river’s 10,000 square-mile watershed must flow through here, so no wonder it has gouged out this cut between the harder bottom and the sediment on the shoals. The bottom material on the shoals is hard because it’s made up of several millennia of oyster shells accumulating to form reefs, with millions of present-day oysters growing on them. The half-dozen ships left in the U.S. Navy’s James River Reserve Fleet swing at anchor out of the channel in the upper part of Burwell’s Bay, across the river from the U.S. Army’s Fort Eustis.

Fish on the sonar at Deep Water Shoals.

This section of the James is the public-harvest James River Seed Area A—one of the natural public oyster beds, rocks, or shoals designated for the harvest of seed oysters—managed by the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) and surrounded by multiple dozens of shallow reefs leased out by VMRC to various private oyster companies. The bend in the river, with Burwell’s Bay at its lower end, tends to throw eddies in the river current that hold oyster larvae (spat) after each year’s spawn, so they settle here to form a vast population of young “seed” oysters. Watermen from nearby harbors like Deep Creek in Newport News and Rescue, just inside the mouth of the Pagan River, harvest them with hand tongs. Large buyboats carry loads of them to plant on suitable leased bottom in other areas of the Chesapeake that have low natural reproduction. This part of the James has been making an extraordinary contribution to other oyster grounds in both Virginia and Maryland for more than a century.

All of those reefs, of course, provide excellent fish habitat. The river from Hog Island down to the James River Bridge, which runs between Newport News and Isle of Wight County, is salty enough to attract species like red drum and croaker, but the upper end is fresh enough for blue catfish. Rockfish live and feed throughout this section, and Burwell’s Bay is a staging area for multiple age classes of Atlantic sturgeon. We spoke to one local angler at the ramp who brings home a steady stream of blue cats and reds.

Lawnes Creek, however, with a comparatively large watershed of its own, is salty at the mouth and fresh in its upper reaches. That fact is evident in the saltmarsh cordgrass growing along both sides at the landing. The fishing pier offers good opportunities for blue cats using cut bait and white perch using grass shrimp, both on appropriate-size bottom rigs. The first turn above the landing is a hairpin, with more than 30 feet of water gouged out by the creek’s currents. It should be good for catfish. The Isle of Wight side of the creek holds broad salt marsh for the first mile, after which the creek meanders, with marsh on the inside and woods on the outside of each turn. A few private docks extend from the Isle of Wight side. Depths in those turns run to the upper ‘teens, with 5 to 7 feet in the reaches, gradually getting shallower.

Another mile along, the marshes begin breaking up into small islands and the vegetation changes to lower salinity plants—first cattails, and then wild rice and other tidal freshwater plants that produce copious seeds for waterfowl and other birds to eat. Access for skiffs stops at the bridge carrying Burnt Mill Road over the creek, though kayaks and canoes should be able to slither under it to explore further upstream. Two cautions, though, for paddlers: first, figure a two-foot vertical range for the creek’s tides and plan around them to avoid being trapped above the bridge; second, figure on at least a one-knot current and plan around that.

The Lawnes Creek bridge.

NOAA’s Tides and Currents website can provide valuable predictions for the river and the creek. Be sure, though, also to factor in how weather might affect conditions in both. In particular, strong northerly or southerly wind blowing against the current can kick up some serious seas in the river. Be sure to wear a life jacket at all times, work out a float plan, and make sure someone knows where you’ll be going.

John Page Williams is a noted writer, angler, educator, naturalist, and conservationist. In more than 40 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Virginia native John Page championed the Bay’s causes and educated countless people about its history and biology.