The few dollars that hunters, anglers, and trappers spend each year on a National Forest Stamp go a long way when putting habitat work on the ground.

By Justin Folks/DWR

The George Washington and Jefferson National Forests span nearly 1.7 million acres in our Commonwealth, providing Virginians ample space to explore the wild. In order to hunt, fish, or trap on National Forest lands in Virginia, one must purchase a National Forest Stamp. Many hunters, anglers, and trappers purchase this four-dollar stamp knowing little more than that if they don’t, they get a ticket.

Many of you may wonder, “what is this National Forest Stamp, and where does the money go?” In a 1963 letter from T. C. Fearnow, an Assistant Regional Forester with the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), to James McInteer, Jr., the editor of Virginia Wildlife magazine at the time, Fearnow included a transcript of a talk he had given at the 1950 Southeastern Wildlife Conference in Richmond, Virginia, about what was known as the “Virginia Plan.”

In the transcript, Fearnow stated: “The Virginia Plan is a remarkable example of cooperative endeavor, under which State and Federal agencies have effectively pooled resources and manpower on behalf of a common cause.

“It was not the creation of any one man’s mind. It is a composite program resulting from ideas of many interested persons. It apparently had its origin in the early efforts of Justus H. Cline of Stuarts Draft, Virginia, to create the Big Levels Game Refuge back in the early 1930s.

“John W. McNair, who was Supervisor of the George Washington Forest at that time, and A. R. Cochran, who was District Ranger on the area from which the refuge was carved, had the vision to get behind this project and give it their full support. Success on this relatively small area demonstrated the possibilities for broader application of the three-way alliance between the Game Commission, the U.S. Forest Service, and sportsmen. Former Game Commission Director Carl Nolting and Executive Secretary M. D. Hart threw the weight of the Commission behind this broad program, and T. E. Clark, who was first associated with the Forest Service and later with the Virginia Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries, filled in many details and refinements that only a technician could supply. Thus the ‘Virginia Plan’ came into being and one wonders why this approach to wildlife management on public lands did not develop earlier.”

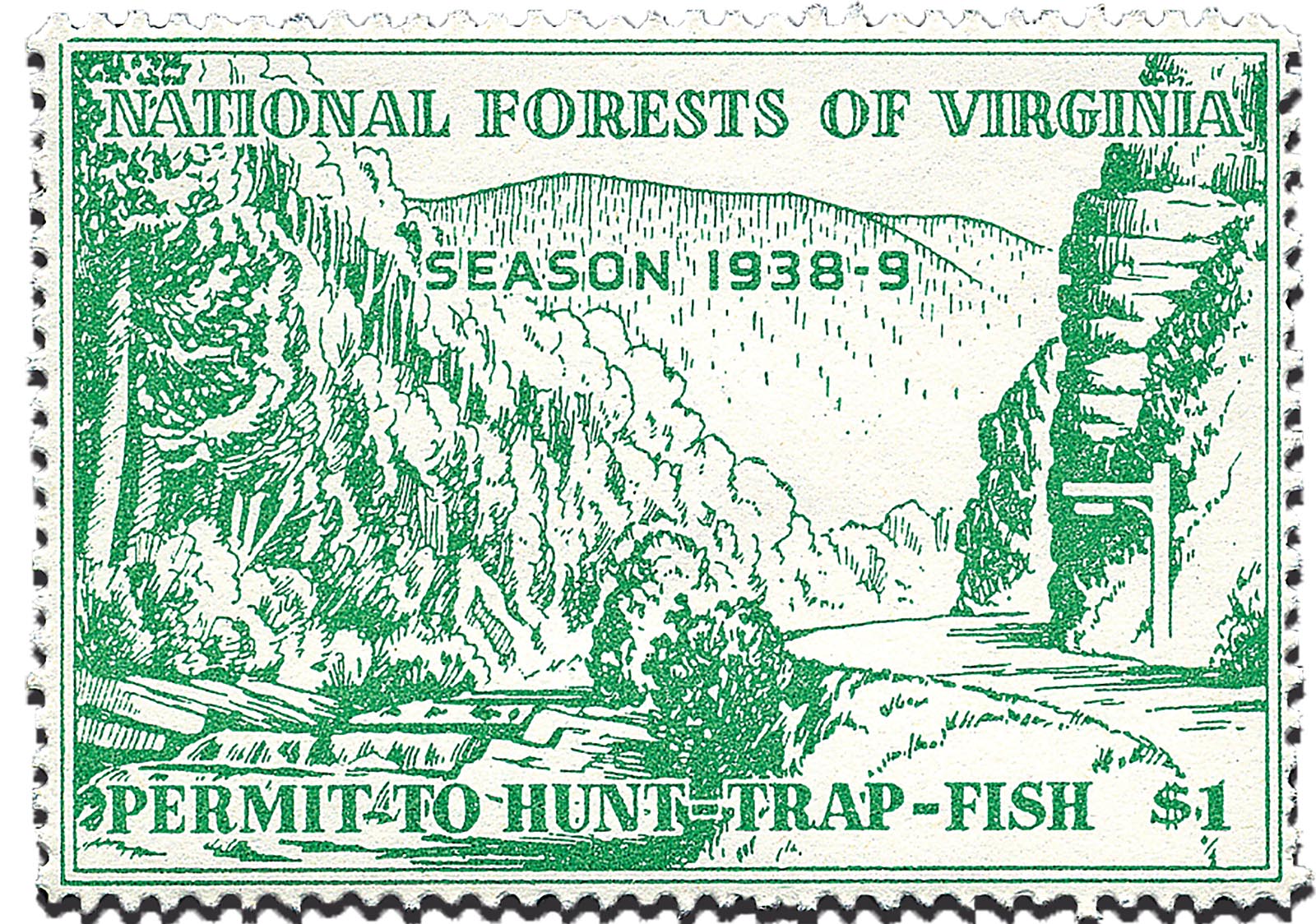

The successful collaboration among USFS, the Game Commission (now the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources [DWR]), and sportsmen at Big Levels spurred this Virginia Plan, from which the National Forest Stamp was born. The National Forest Stamp was unveiled for the 1938-1939 hunting season at the cost of one dollar. Funds generated from this stamp were (and continue to be) used to implement wildlife habitat projects on National Forest lands within Virginia.

Habitat Work is Better Together

In early years, while some habitat improvements were made, much of the funding was used for wildlife restoration efforts such as stocking deer and turkeys. Funds were also used to employ resident wildlife managers to work on National Forest lands. Fearnow’s transcript states, “Each of the wildlife managers on national forest land is provided with a small allotment of funds with which to employ local labor and, at times, the total wildlife work force may run as high as 100 men on the two Virginia Forests.”

Although this workforce model no longer exists, habitat is still being restored and maintained. Each year, staff from DWR and USFS meet to prioritize which planned habitat projects will receive funding from Forest Stamp dollars. As stated in code, funding from stamp dollars must be used for projects related to hunting or fishing (since hunters and anglers are the ones who must purchase these stamps), but each staff member knows full well that the benefits of each project reach well beyond game species. Example projects include removing dams to improve fish passage and fish habitat, implementing prescribed burns, restoring native meadows and grasslands, managing non-native invasive plants, liming of native trout streams to mitigate the effects of acid rain, maintaining forest openings, improving public access, and more.

Native meadow restoration work on the Clinch River District within the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests has benefited many important pollinator species, songbirds, and other nongame species while offering forage and cover for deer, turkey, and ruffed grouse. Much of this work would not be possible without the help of volunteers. Photo by Lauren Reker/USFS

“I hunt in western Virginia on George Washington National Forest in search of quality whitetail bucks and have had good success around timber stand improvements, clear cuts, and prescribed burn units. Anywhere there is a change in habitat from old-growth forest is usually a good place to start finding deer on National Forest,” said Josh Simmers, a hunter who frequents National Forest lands.

Through the years, additional partners have collaborated with DWR and USFS with both financial and technical contributions. Organizations such as Trout Unlimited (TU), the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), and others have helped see habitat projects through. NWTF has been particularly instrumental in getting habitat on the ground by assisting with the administration of project contracts and the purchasing of supplies and equipment. Without NWTF’s involvement, habitat work would be held up in a sea of governmental red tape and purchasing restrictions. Beyond contract administration and purchasing, NWTF has also contributed financially through its “Superfund.”

The NWTF Superfund consists of moneys raised from NWTF banquets across the country—funds that are then used for habitat work to benefit wild turkeys and other wildlife in the states in which the funds were raised. After suffering some setbacks due to the COVID pandemic, NWTF has rebounded significantly. Just this past year, NWTF was able to fully fund all proposed Stamp projects when many typically go unfunded (there are always more projects than there are funds available). It’s only fitting that such an organization—and one founded in Virginia no less—is such a key partner with the one-of-a kind National Forest Stamp program that began so long ago as the Virginia Plan.

Another great partner in western Virginia is the Appalachian Habitat Association (AHA), whose mission is to promote habitat management work on public lands primarily in Alleghany, Augusta, Bath, Botetourt, Craig, and Rockbridge counties. The AHA has helped with many projects on both state and federal lands. Countless volunteers have also contributed their time and sweat to complete projects over the years, helping these dollars stretch even further.

A streambed and streambank restoration project on Dry Run in the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area (before on left, after on right) improves aquatic habitat and reduces sediment load to benefit trout and numerous other aquatic species. Photos by David Hart

Quite the Conundrum

Unfortunately, Virginia has seen a decline in the purchase of National Forest Stamps over the years, and with it, a decline in the amount of funds available for critical habitat and infrastructure work. This has coincided with a declining number of hunting license sales. Ironically, it might be a little of a chicken/egg situation, as the declines in both hunting license sales and National Forest Stamp sales could be attributed to declining habitat quality on National Forest lands for game species. A decline in habitat work yields less game to encourage those to buy the stamp that helps create and maintain habitat.

It’s quite a conundrum, but this is only one piece of the puzzle, as hunting license sales have been declining significantly for decades nationwide. To compound the problem, the cost of labor, supplies, and equipment only continues to increase annually, while the cost of the Forest Stamp itself has remained minimal for 75 years (it was $1 at its inception in 1938 and is currently $4).

What can you do to help? Purchase a National Forest Stamp and explore the wild of our National Forests. Get involved with your local chapters of NWTF, TU, or other conservation organizations that support our efforts. Reach out to your local DWR or USFS biologists with project ideas and help raise funds to get them done, or volunteer to help on work days.

Although the National Forest Stamp program is largely driven by hunters and anglers, these projects are critical for many nongame species. If not for the early efforts of those forward-thinking conservationists in the 1930s and their Virginia Plan, many of the wildlife species we enjoy today may not exist. If we don’t continue that effort, future generations of our National Forest users may not be as fortunate.

Why Just Hunters, Trappers, and Anglers?

Many outdoor enthusiasts who purchase the $4 National Forest Stamp to be able to hunt, trap, and fish on National Forest lands wonder why other outdoor enthusiasts, such as hikers or wildlife watchers, don’t also need to complete this purchase to access the land.

Dawn Kirk, forest fisheries biologist at the U.S. Forest Service, explained: “The National Forest Stamp goes back to 1938 ($1) when the Virginia State game agency and Forest Service first developed a plan to improve wildlife and fish habitat on National Forest to benefit hunters and anglers. Except at developed recreation sites, there is no charge to recreate (hike, bird-watch, berry-pick, bike, disperse-camp, etc.) on the National Forest. The state has jurisdiction over game species management and sets hunting and fishing regulations and permits; the Forest Stamp was seen as a way to support the habitats that allow for that recreation. There has been discussion in the past suggesting the state develop a voluntary ‘stamp’ for hiking and wildlife viewing, where the proceeds would support those activities on National Forest, but it has not moved past initial discussions and been incorporated into the code of Virginia.”

Justin Folks is the DWR deer project leader.

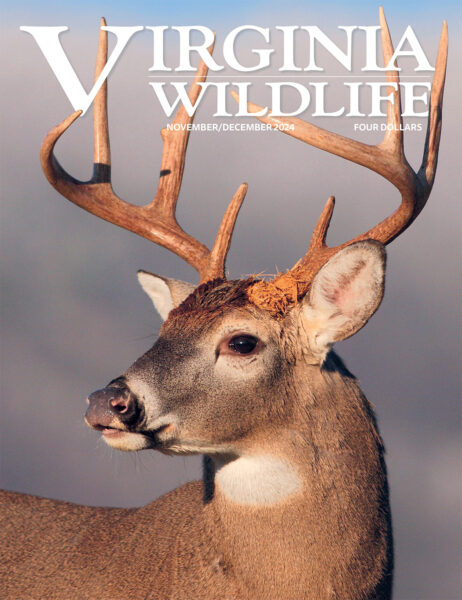

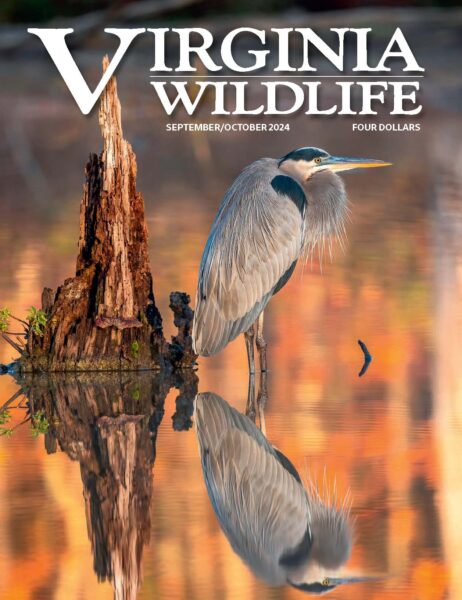

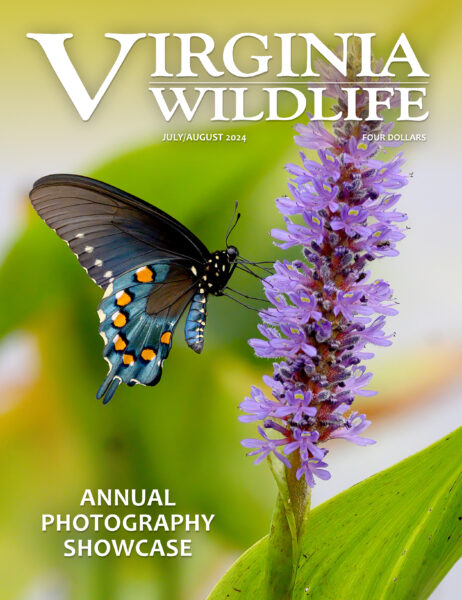

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe