How a coordinated approach has helped Atlantic sturgeon rebound in Virginia's waters.

By John Page Williams

Splash! CRASH!!

“That was a BIG fish! What happened?”

We’d just witnessed a five-foot male Atlantic sturgeon breaching clear of the James River in the channel at Jones Neck. We smiled as the ripples subsided. My daughter, Kelly, her daughter Mary Page, a fourth-grade classmate, and I were headed back from Henricus Historical Park to Deep Bottom one day in the fall of 2019 in my skiff. The girls were studying Virginia history and wanted to learn about Pocahontas, so we visited Henricus the same way the Powhatan princess did 406 years earlier—by river. Seeing the magnificent fish was a bonus, but since it was mid-September, not a surprise.

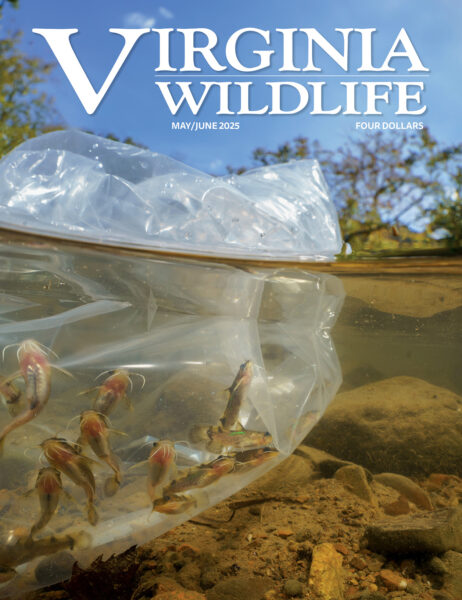

An Atlantic sturgeon breaching in the James River.

Nor would it have been for Pocahontas. In Tsenacomoco (her people’s name for Virginia’s coastal plain), the big fishes’ meat had been a staple for centuries. Atlantic sturgeon spawn in freshwater over clean, hard bottom, live their first years in the estuaries, and migrate out at the age of 2 to 3 years, roaming the Atlantic’s continental shelf.

Historians tell us the fall spawning-run sturgeon helped the Jamestown colonists survive that difficult first year of 1607 (after Native American fishermen taught them to trap the big fish for sustenance). Atlantic sturgeon remained valuable for people along Virginia’s rivers for 300 more years, becoming common enough that markets labelled them “Charles City Bacon.”

Caviar and Collapse

Sturgeon for sale on a Maryland dock in 1901. By 1920, there weren’t enough sturgeon to support a fishery.

Atlantic sturgeon are anadromous fish—born in freshwater, then migrating to the sea and back again to freshwater to spawn. During the 19th century, Virginia watermen learned to salt and cure caviar from sturgeon during their spring spawning run up the rivers, and the market exploded. They had better equipment than their Native and colonial predecessors—gill nets, haul seines, and skiffs purpose-built for the fishery—but they understood less about the sturgeons’ life cycle than Pocahontas’s people had.

Heavy fishing for mature females with eggs persisted. What no one understood is that Atlantic sturgeon, though long-lived (up to six decades), don’t mature to reproduce until their teens (early for males, late for females), and the big females spawn only every two or three years. The caviar boom caused the watermen to harvest the spawning stock, with predictable results.

Meanwhile, land clearing without soil conservation, sewage from the Commonwealth’s growing urban population, and pollution from the Industrial Revolution fouled the rivers. The combination ravaged the river bottoms where the sturgeon had for millennia vacuumed up worms, crustaceans, shellfish, and small finfish. The silt destroyed the eggs they deposited on rocky bottom.

It was no surprise, then, that the bottom dropped out between 1890 and 1920. In the 20th century, seeing a sturgeon anywhere—alive in a springtime gill net, on ice in a fish house, or floating dead from a ship strike in a narrow river channel—was a story for the newspapers. They were gone, ghosts from other centuries. The directed fishery ended by 1970.

Regulatory changes, including fishing bans in Virginia and Maryland, went into effect to protect the sturgeon, while the Clean Water Act of 1972 and the first Chesapeake Bay Agreement in 1983, led to broad cleanup programs that are restoring health to Chesapeake rivers. Even so, biologists feared there was no more natural reproduction of sturgeon in Maryland or Virginia.

Hiding in Plain Sight

It turns out, though, that the ghosts had been hiding in plain sight. During multi-agency work on recovery of striped bass stocks in the late 1980s, Albert Spells of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) suggested also studying sturgeon. Later, as project leader for the Virginia Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office of USFWS, he wondered if they weren’t looking in the right places. Jim Owen, then-liaison with watermen for the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) Sea Grant Marine Advisory Service, remarked, “You know, Albert, watermen are catching sturgeon, but they won’t tell you till you put some money on the table.”

At the time, other fishery scientists believed there were not enough mature Chesapeake Bay Atlantic sturgeon to maintain self-sustaining populations. Spells, however, did not agree, based on Owen’s information and credible evidence of a juvenile sturgeon caught on hook and line from the York River in 1996.

In 1997, he assembled a small fund from USFWS, the Commonwealth of Virginia, the state of Maryland, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), and VIMS to offer bounties for watermen who caught and retained sturgeon alive for examination, tissue sample collection for DNA analysis and aging, and tagging.

Tissue samples for DNA analysis went to the U.S. Geological Service’s Leetown Science Center (West Virginia). Suddenly, there were several hundred fish, many 2- and 3-year-olds, including both Atlantic and even one rarer shortnose sturgeon.

Albert Spells, project leader for the Virginia Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, felt compelled to look for sturgeon. Photo courtesy of USFWS

An adult Atlantic sturgeon getting tagged. Photo courtesy of VCU Rice Rivers Center

It soon became obvious that most sturgeon were coming from the James River in spring, possibly because watermen were most active there, setting nets for rockfish from the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel upstream past Jamestown to the Chickahominy River’s mouth. That fishery posed both problem and opportunity, because unintended sturgeon catches threatened both fish and nets, but the watermen were learning more about catching them. In the early 2000s, Chris Hager, a fisheries bycatch specialist with the Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program at VIMS, began working with watermen Kelly Place, George Trice, and Jimmy Moore on designs for nets that caught rockfish but avoided sturgeon.

Place also worked out funding from Sea Grant to tag Atlantic sturgeon with Trice and Moore, under a VIMS scientific collecting permit, in cooperation with Spells and USFWS. Concentrating on channels between Cobham Bay and Burwells Bay, they implanted external and acoustic tags in sub-adults (20″ – 40″), while collecting small clips of fin and tail for age and DNA analysis. Over time, recovery of tagged fish has shown that, as Spells says, “They wander more than we thought.”

In March 2004, Baywatcher, the CBF education/workboat based at Jordan Point near Hopewell, caught a six-inch sturgeon in her trawl net in the mouth of Herring Creek with an eighth-grade class of Earth Science students aboard. It was the first evidence of natural reproduction in the James River in 50 years. Spells smiled when he heard the news, as did the students and the boat’s educators.

The catch was accidental, but “The more data points, the more eyes and ears, the better,” said Spells. He began offering public outreach programs, including sturgeon in tanks. “People started falling in love with them,” he said, smiling. The James River Association (JRA) joined this effort with educational materials and field trips for schools and the public.

James River Rats

In the spring of ’04, a pair of James River rats from different generations took professional interest in sturgeon. Chuck Fredericksen, recently retired from Fort Lee, became Lower Riverkeeper for JRA, putting him on the James every day aboard a patrol boat. He had fished the river all his life and participated in Hopewell’s volunteer Sturgeon Resurgence Committee.

Meanwhile, Hopewell native Matt Balazik completed undergraduate studies at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and began a Master’s program in Fisheries under Dr. Greg Garman of VCU’s Rice Rivers Center, near the USFWS Office at Harrison Lake. When Spells looked for help with the tagging project, Garman recommended Balazik.

Balazik had grown up on a riverside farm, fishing with his older brother Martin, but he never saw sturgeon in the 1980s and ’90s, even during the fish kills that plagued the river then. He helped the watermen involved in the project with gear, monitored their catch, and filled out reports. “I learned a lot from those professional fishermen,” he said. “I visited and listened to a lot of people up and down the coast.”

In the fall of 2007, the river people began seeing sturgeon breaches, along with, unfortunately, ship strikes. Balazik and Fredericksen began fishing for them, while Spells helped with gear. “No one knew how, beyond conventional drift-netting,” said Balazik. “It took us several years to get okay and several more to become efficient,” he said. They kept tanks in their skiffs to keep the fish healthy while measuring and tagging.

Balazik was convinced that the fish he was handling were spawning, based on their condition, the historical accounts from Jamestown, and the size of the juvenile caught by CBF. Spells argued against existence of the fall run until 2013, but evidence built. In 2018, JRA field educators and students aboard the association’s Spirit of the James pontoon boat caught sturgeon larvae in a plankton net. Balazik confirmed the catch and found more.

“When JRA captured those larvae,” Spells said with a chuckle, “that was the seal. So now, rather than arguing with Matt, I just bow to him.”

Matt Balazik holds the first known female sturgeon to be caught during his research. Photo courtesy of VCU Rice Rivers Center

Endangered Species Listing

In 2009, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) petitioned NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to consider five Distinct Population Segments of Atlantic sturgeon for listing under the Endangered Species Act. In response, NMFS in 2012 listed the Chesapeake Bay, New York-New Jersey Bight, Carolina, and South Atlantic segments Endangered, and the Gulf of Maine population Threatened. The listing opened research funding from NOAA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center (ERDC).

Side-scan sonar reveals sturgeon swimming in the James River, making them countable for research. Photo courtesy of VCU Rice Rivers Center

Balazik was the right person at the right time for the sturgeons’ Endangered Species listing. He finished his Ph.D. that spring, became a full-time VCU employee, and took a part-time position with the Corps’ ERDC, working on relationships between endangered species and channel dredging. “I’ve spent time talking with dredgers, learning a lot from them and the Corps: how it can be done better, more efficiently, with minimal environmental effects,” Balazik said.

As evidence of spawning increased, Fredericksen had an idea. Concerned about excessive sediment fouling eggs, he wondered if building a spawning reef was possible. In 2010, JRA collaborated with VCU and Luck Stone Corporation to construct a hard-bottom reef standing two feet above the bottom on a channel edge beside the USFWS Presquile National Wildlife Refuge. Two more followed in 2012 and 2014, one with Vulcan Materials on the south side of the channel just below the I-295 Bridge and the second with Luck Stone in the cut-off at the base of Jones Neck. Hopefully, these artificial spawning reefs will be used by female sturgeon.

One new research tool is a side-scan sonar developed by ERDC and several partners that records detailed images of sturgeon, allowing the VCU crew literally to count fish, including individuals around the reefs during the runs. “I really don’t see the surface of the river so much now,” Balazik said. “I can visualize the bottom so much better because of sonar, GPS, and electronic charting. It’s important that we document their spawning areas and get good estimates of how many are in the river.”

A Coast-wide Tracking System

In 2013, Balazik joined other sturgeon scientists in genetic analysis to work out relationships between stocks in other river systems. Coordinating research allows scientists to track movements of individual fish with acoustic tags during the long migrations in their life cycle. The project deploys and monitors receiver arrays for the acoustic tags throughout the entire Chesapeake Bay, in cooperation with other research institutions coast-wide under the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry Network. The standardized receivers detect tagged fish within a half-mile. Scientists monitor the receivers monthly, building information on sturgeon movements throughout the Chesapeake while supporting other research efforts along the Atlantic seaboard.

Balazik continues to study the relationship between the fishes’ age and growth, adding his own fieldwork on live and recovered dead fish to earlier data from Place and Spells, studying both the spring and fall seasons. “I’m concerned about the spring run, based on juvenile captures,” Balazik said.

A juvenile Atlantic sturgeon. Photo courtesy of VCU Rice Rivers Center

“In 2020, we had 55 spring recaptures versus 980 fall recaptures and 60 new fall fish. Most of the young-of-the-year fish are fall run. There’s a good chance that spring net fishing for other species damaged those sturgeon runs years ago.”

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) worked closely with VCU’s Rice Rivers Center in early field studies and data management. Once NMFS listed the fish as endangered, the agency maintained the receiver array, but Rice Rivers has taken over that task now. DWR remains a partner on the NOAA/USFWS permit to handle Atlantic sturgeon and looks actively for ways to contribute as program evolves.

JRA, for its part, continues to lead a broad partnership of government agencies, non-profit organizations, businesses, and citizen volunteers in improving water quality, restoring habitat, and educating the public. The great improvement in the river’s health over the past 50 years has certainly played a key role in the sturgeons’ rebound. The organization and its partners also address specific threats like entrainment, in which the cooling water intakes at the river’s power stations suck in sturgeon larvae.

Thanks to the heavy rains throughout 2018, “all the stars aligned,” Balazik said. “The spawning habitat was available. The 2018 year class is the strongest we’ve seen to date. We’re monitoring them right now. They are 55-65 cm fork-length (22″-26″). We’re catching them from Dancing Point, at the mouth of the Chickahominy, to Skiffes Creek on the upriver side of Fort Eustis. There’s lots of channel dredging in that part of the river, so we’re watching the effects closely, looking to see where they go. I’m excited to follow these 2018 fish as they grow. That’s my mission. I figure I’ll retire after I catch the first mature, spawning females from this year class around the fall of 2035.”

Epilogue

While the James River has been action central for Virginia’s Atlantic sturgeon, they are turning up in other Chesapeake rivers. Riverman Mike Harley continues to catch and release a few subadult sturgeon in the Potomac. On the Rappahannock, pound-netters Wayne Fisher and Albert Oliff release several sturgeon each year between Tappahannock and Port Royal. Balazik has caught and tagged a few Rappahannock sturgeon and plans more work there. A U.S. Navy-funded research team working with the Pamunkey Tribe has caught and tagged apparently spawning sturgeon in the Pamunkey River and its sister, the Mattaponi.

In June 2019, Kevin Falvey, an angler on New York’s Long Island South Shore, was drifting squid strips for flounder when a powerful fish struck. After a tough fight, he netted and released a 40-inch, sub-adult sturgeon. Smart money would say that fish had come from the Hudson, but the Pamunkey team last October caught a large, tagged female full of eggs. According to the USFWS database, she had been caught in a research net and tagged off Long Island in 2006 as a sub-adult about the size of Falvey’s fish. So, 12 years later, she had returned to her native river to spawn.

Falvey’s fish could belong to any of the Atlantic’s Distinct Population Segments, including the Chesapeake. Since it carried no tag, though, its origin remains a mystery. Atlantic sturgeon have been on Earth for tens of millions of years, and they might just survive even the worst damage we could do to them. Ghosts no more, theirs is a story of hope. We still have work to do—improving water quality, reducing soil erosion, learning to be smart about dredging, managing fisheries, and confronting climate change—but our sturgeon give us encouragement that we are headed in the right direction. We hope Pocahontas is looking down and smiling as these iconic fish rebound and we take better care of Tsenacomoco.

In more than 40 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Virginia native John Page Williams championed the Bay’s causes and educated countless people about its history and biology.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe