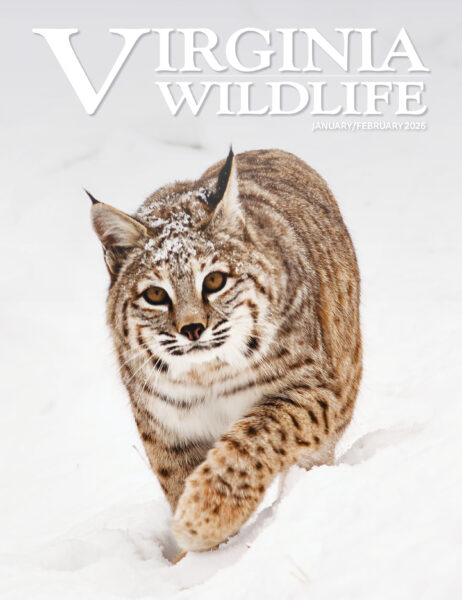

At Goshen and Little Mountain WMA the area is checked for hot spots after the fire. Photo by Ron Messina/DWR

By Ron Messina/DWR

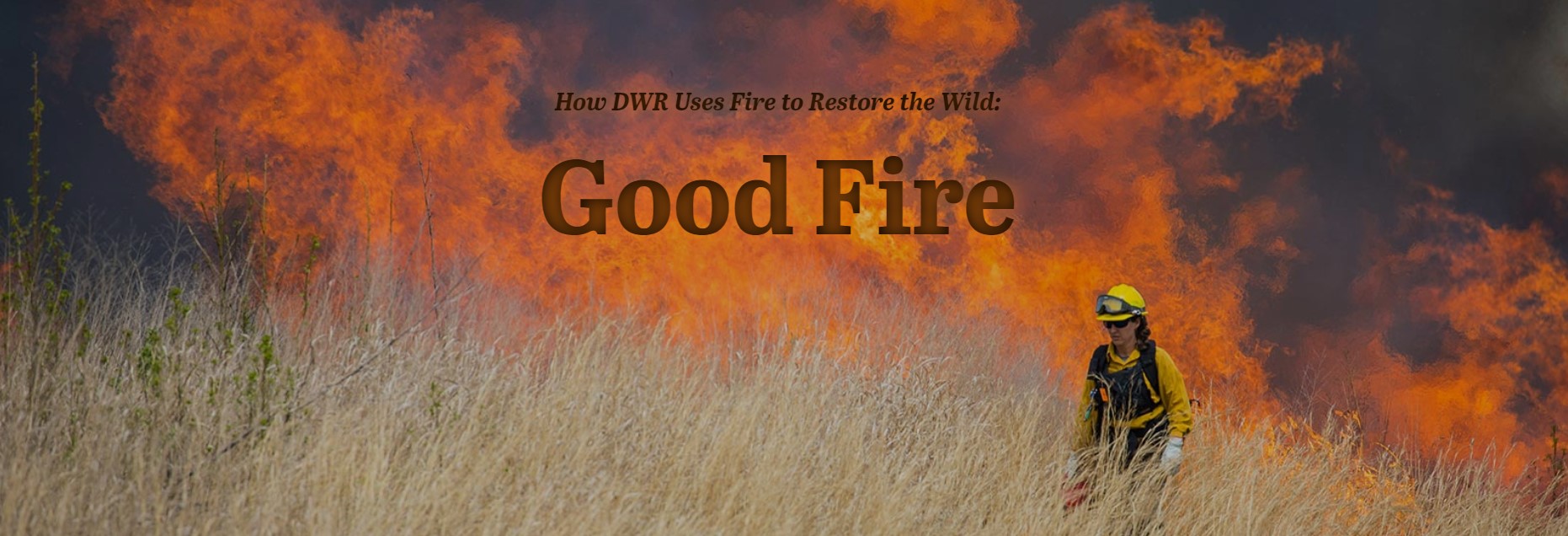

A wall of smoke and fire rolling across a Virginia mountaintop is normally a sight to stoke fear in nearby hikers and send local firefighters scrambling for their brush trucks.

But this fire, ignited intentionally at the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ (DWR) Goshen and Little North Mountain Wildlife Management Area (WMA) by a professional crew using drip torches, two-way radios, and ATVs outfitted as fire engines, is neither out of control nor meant to run wild.

It’s a prescribed fire—using carefully located firebreaks and thoughtful ignition patterns to reduce undesired plants, leaves, and debris. This creates patches of bare ground that are essential for many wildlife species and allows essential sunlight to reach seeds, beginning a cycle of new growth on the landscape.

Both wildfire and using fire intentionally have had impacts on wildlife ecosystems for hundreds of years. There’s evidence that indigenous people and colonial settlers alike conducted controlled burns of certain areas for many reasons—from attracting wildlife to an area to clearing land for crops or establishment of home sites. During the early part of the 20th century, with increased residential development in wooded areas and a shift in attitudes toward wildfire—including the rise of the “Smokey the Bear” campaign to prevent wildfires—fire suppression became more of a priority than use of prescribed fire.

At the firing boss’ signal, a row of igniters wearing full protective gear—colorful hardhats and shirts and pants made of fire-resistant Nomex® fabric—step forward to light a long line of fire. Flames erupt behind them in the thick field of low shrubs and small trees. These first flames are lit against the wind and burn slowly into the designated burn area, called the burn unit. Eliminating fuels near the fire line increases the safety factor. This technique is referred to as a “backing fire.” Far down below, another line of fire is lit. This fire moves quickly with the wind, burning across the meadow in a matter of minutes with a loud crackling sound and sending smoke high into the sky. When the main fire meets the backing fire, they both begin to stall out, just as planned.

Igniters in protective gear light a line of fire. Photo by Robert B. Clontz

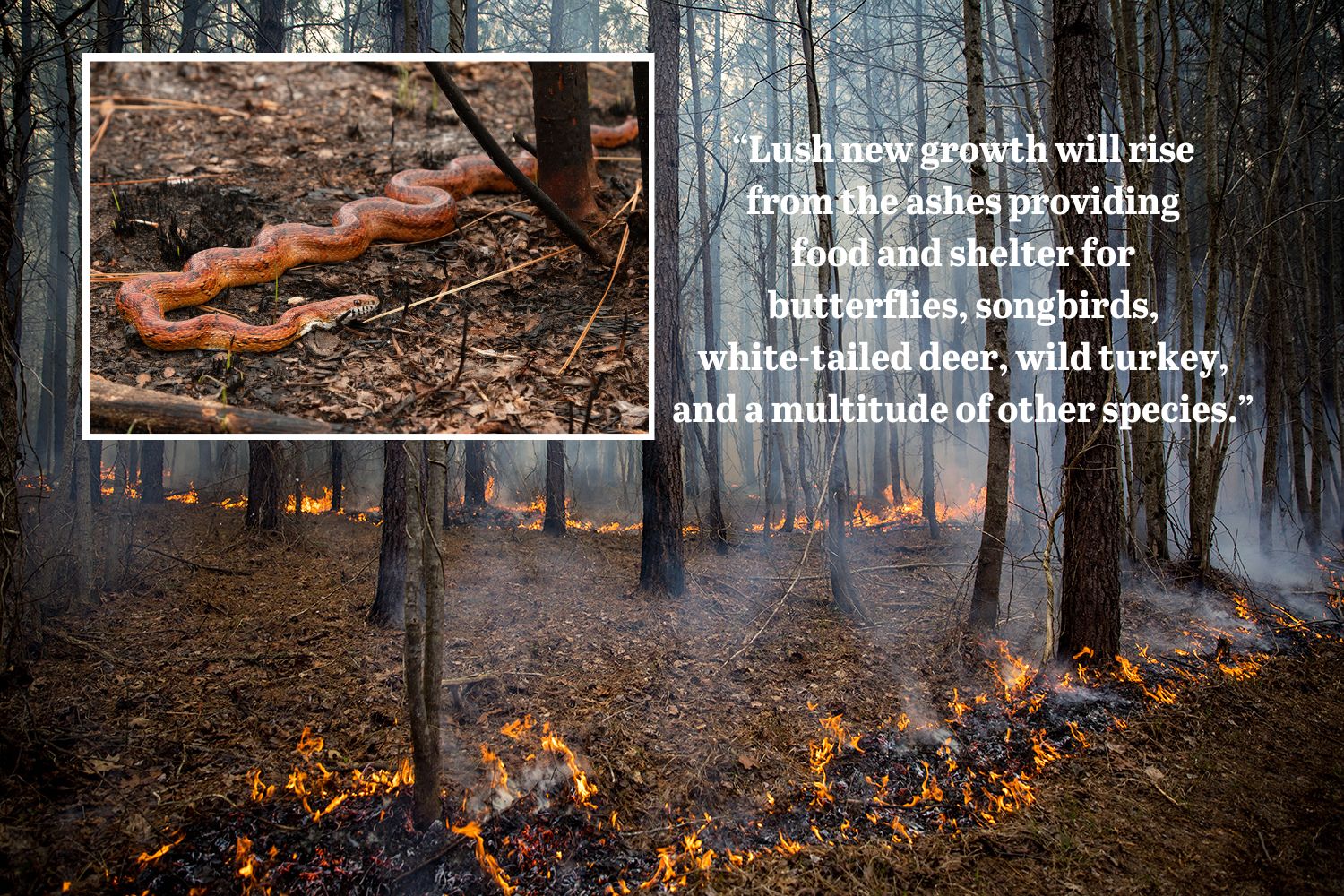

The burned and blackened mountainside may be startling to view, but within a matter of weeks it will change. Lush new growth will rise from the ashes, providing food and shelter for butterflies, songbirds, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, and a multitude of other species. Goshen’s unique, high-elevation ecosystem of native grasses and flowers will again bloom and thrive. The fire will have done its job.

A Conservation Tool Like No Other

The conservation community calls it “good fire,” and it’s a stunningly effective tool for stewards of the land to deploy to enhance habitat.

Burning the earth in order to improve it might seem counterintuitive at first, and the fire crew setting the land ablaze might resemble some post-apocalyptic nightmare from Ray Bradbury’s novel, Fahrenheit 451. But this isn’t science fiction—it’s tried and true wildlife habitat management that’s being used increasingly on the landscape here in Virginia by DWR alongside a number of partner organizations and private landowners.

Walking out of the smoke along a burn line, Hunter Ritchie, the Wildlife Area Manager (WAM) in charge of DWR’s Highland County WMA, surveys the area and checks in with his team via radio. Communication between all members of the fire crew is essential. A hotspot detected on a flank line by one of the spotters is quickly extinguished to keep the fire contained to the target area of the burn unit. The mountain buzzes with activity as ATVs cruise the perimeter and fire- fighters on foot rake hot embers.

Ritchie directs and participates in many prescribed fire events in his area, the mountainous tracts of Highland, Goshen, and Gathright WMAs in western Virginia. He says fire can have a transformative effect on the land.

“Sometimes you’ll burn and then see some awesome stuff, like some of the native flowering plants and grasses that were never planted. They were there in the soil, in the seedbed, dormant for decades,” Ritchie said. “You run a fire through there and the following spring those wildflowers just blow up! There are colors and sounds and bees everywhere. It’s hard to imagine when it’s just been burned; it’s a real leap of imagination.”

Fire works transformative magic even on smaller parcels in eastern Virginia. DWR Upland Game Bird Biologist Mike Dye, a fire team member who works in the Piedmont, says using fire on the landscape in tactical ways produces quick results.

“On the Mattaponi WMA [in Caroline County], we did a prescribed fire that was only 50 acres, but within four weeks of that burn we had quail in that unit calling and trying to find mates,” Dye said. “It was very obvious that it was a result of the burn—so many more quail were in that one area versus the other areas that were similar habitat that had not been burned.”

Animals are quick to take advantage of any changes to their environment. Sightings have been documented of wild turkeys scratching up and feasting on roasted insects that have been exposed on still smoldering ground only hours after a fire. Wildlife are generally pretty well adapted to fire, especially lower intensity prescribed burns. Providing avenues for wildlife escape during burns is something burn managers take into consideration. There can be some short-term impacts to wildlife, but many species will take advantage of the newly rejuvenated habitats, and the improved habitat will better support many species as they work to survive and raise young.

“The effect of fire for habitat work is something that can’t really be replicated in any other way,” Dye said. “We can’t get out there with a tractor and just dig the area and have the same effect. We can’t get out there with chainsaws and have the same effect as far as habitat manipulation. It’s just kind of its own entity; it’s part of what these ecosystems were historically.”

Restoring the Longleaf Pine Savanna

DWR’s Habitat Education Coordinator, Stephen Living, agrees. “All of these habitats are fire-adapted. This was an ecosystem in which fire occurred naturally and was for thousands of years introduced by indigenous peoples,” he said. “We’re just bringing that back on the land.”

At DWR’s Big Woods WMA in Sussex County, Living kneels down to examine the effects of a fire on a native tree, the longleaf pine. He points to a few blackened pine needles along the base of a sapling. “You can see where fire burned through here, killing off the competition for this tree, but the longleaf has adapted to fire so it doesn’t really impact it,” he noted. Indeed, the marble-sized green buds on the longleaf sapling are unfazed, while the grasses and woody vegetation around it are gone.

Virginia’s conservation community is making a unified effort to restore the longleaf pine, a tree Living calls “iconic.”

Prescribed fire helped create habitat needed by the federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker. Photo by Lynda Richardson/DWR

In colonial times, when longleaf pine savannas ranged throughout coastal southeastern Virginia, the tall, straight trees were cut for lumber, to make turpentine and pitch, and used for masts on sailing ships. Today they’re valuable for another reason—helping spur the restoration of pine savannah in Virginia. Longleaf pine are fire-dependent even as young seedlings. Managing these stands with prescribed burning helps to create incredibly biodiverse habitat. Mature longleaf pine are also the preferred nesting tree for the state- and federally-endangered red-cockaded woodpecker (RCW). These rare birds nest exclusively in old-growth pines and forage for insects along their bark. Currently, all of Virginia’s RCW are nesting in large mature loblolly pine, but we look forward to the day when we once again have RCW in longleaf pines.

DWR Region 1 Lands and Access Manager Matt Kline oversees the Big Woods WMA. He says he was surprised after DWR and partners conducted the very first burn there because woodpeckers he was certain “we still had some time before the red-cockaded would show up.” But that wasn’t the case—if you burn it, they will come.

“After introducing fire, we already had some RCWs exploring in there. It doesn’t happen that way often in science, but it was kind of set up in a good position to have emergent growth that that species needed,” Kline said.

The RCW may be a marquee species at Big Woods, but fire also supports many animals in a pine savanna. Quail, wild turkey, deer, and songbirds like the prairie warbler all do well in a habitat with grassy understory and open spaced trees. The fires at Big Woods control the growth of some less desirable hardwoods—sweet gum and red maple, primarily.

According to Living, fire can be a reset to the soil, reducing fuel loads and thereby lessening the chance of a wildfire, while also encouraging the germination of plants that feed and shelter a diversity of wildlife. “You’re reducing what we call the standing dead biomass—that heavy stuff that might inhibit wildlife movements. You’re creating open ground that species like box turtles or quail might like. And you’re creating a flush of new growth of grass and flowering plants,” he said.

Every Fire is Unique

Weeks, and sometimes even months, of planning go into the preparation for a single prescribed fire. A burn plan that outlines the goals for the burn and every aspect of what will take place on the burn unit is created. Finding a perfect day to burn—one with the right balance of wind and humidity— usually takes even more time. Too much humidity and the fire won’t burn hot enough; too little humidity and it could burn too hot and fast. Having the right wind speed and direction is important, also; wind from the wrong direction could blow smoke towards nearby residents and cause problems.

Other details, like access for people and equipment with entry and exit routes, control lines, and even alerting local emergency services ahead of time, are all critical. Even having the right ratio of gas to diesel in the drip torches for the individual day’s conditions matters. Finally, when all the conditions are perfect, there may be only be a short window of time to get everyone on the ground to conduct the burn.

The burn crew gets together to discuss strategy before the burn. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

“There are probably 40 hours of planning that go into it before you even strike the match,” said Rebecca Wilson, long- leaf pine restoration specialist with the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Division of Natural Heritage who frequently burns with DWR staff. And she says that first match will be used to light a small “test fire,” to confirm conditions are good before the larger burn can take place.

DWR Wildlife Area Manager Samantha Lopez enjoys the challenge of it all, especially writing a good burn plan. “I think it’s an opportunity to be creative. As weird as it sounds, ‘a fire is not fire, is not fire,’” she said. You can do what you think is the exact same type of fire, but a five-degree difference in humidity can have totally different effects. Different times of the year, or even just a slight difference of the fuel that you’re burning, have an effect. You can’t think, ‘let’s do the same blueprint and get a great burn every time.’ Every burn is different.”

DWR’s fire crew are all adding prescribed fire to their day jobs. The fire crew includes staff that work as fisheries and wildlife biologists, Conservation Police Officers, Wildlife Area Managers, and more. Time digging lines and doing prep work such as dropping hazardous trees allows for plenty of bonding with coworkers from different regions. “You end up learning more about these people than you ever thought you would,” Lopez said. “I learned that one of the other firefighters is teaching himself Japanese so that he can be a translator.”

Conditions in the field at a prescribed fire can be brutal, and the terrain rugged and remote. “It takes a certain type of person to find this work challenging and interesting because it’s definitely a dynamic habitat management tool,” said Living. “It requires a lot of focus because it’s hot or it’s really cold, and it’s really smoky. It’s a really long day. We require a work capacity test. Our staff is required to do at minimum the moderate level, but we encourage them to qualify for the arduous level. That just ensures they have the conditioning to go through a really long, hard day of very physically demanding work in challenging conditions.”

The Outdoors are Better Together

One way the DWR fire crew handles the immense workload of a prescribed fire is to partner with like-minded groups and agencies, all of which have certified staff members trained in safety and logistics. These strong partnerships include sharing of resources, equipment, knowledge, and personnel. Mobilizing more resources provides a bigger impact, allowing for bigger burns of more acreage.

Kline enjoys the teamwork aspect of a burn. “We get to work with and learn other things from other agencies,” he said. “We work a lot with The Nature Conservancy, the Department of Conservation and Recreation Natural Heritage, the Department of Forestry, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and the U.S. Forest Service. We’re all working for conservation, and we all have different goals and objectives on those lands, but in the end, fire is a tool that we use in all these landscapes and it’s just a great partnership.”

Big Woods WMA begins its renewal after a prescribed burn. Photo by Robert B. Clontz

There’s a conservation community spirit evident in the field on a prescribed burn. The connection between the various fire team members is one that goes beyond agency lines or public/ private designations. No matter the patch a crew member wears, everyone is working together to safely burn a parcel of land in order to improve the habitat and make conditions better for wildlife. It’s a camaraderie built on smoke and sweat.

Word is spreading about good fire, and the interest in using it on private lands is increasing as landowners are finding ways fire can help them meet a variety of habitat goals.

Landowners can enroll in the Virginia Department of Forestry’s Certified Private Manager program, which provides training and information on the basics of prescribed fire application, as well as Virginia’s laws and regulations pertaining to prescribed fire. They can become fully certified to burn on their own lands. Private landowners may be put off by the relatively complex fire operations that agencies execute with crowds of Nomex®-clad firefighters and specialized equipment. This level preparation and training may be necessary for managing large blocks of habitat in challenging terrain, but executing simpler burns at a small scale need not be so intimidating. With proper planning and an eye on the weather conditions, it’s possible to burn safely with more modest resources. The Virginia Prescribed Fire Council is working to provide a variety of resources for landowners interested in fire: vafirecouncil.com.

After a long day on the burn unit, Lopez reflected on what the effects of prescribed fire mean to her. “The big thing is, ‘How loud is the forest?’ When you walk into a forest, it shouldn’t be quiet,” she said. “You should hear bugs, you should hear birds calling and woodpeckers pecking.” Older mature forests can be important for a variety of wildlife, but many species on the list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need require something different, which is created with fire.

“When you go into a meadow or a really young, open forest, it’s just so loud,” Lopez said. “That’s one of the greatest things—walking in and just having that classic soundtrack— birds and bugs and everything just being so loud and peaceful out in the middle of the woods, in the middle of nowhere.”

Ron Messina is the Video Production Manager at the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

To see even more about how DWR and partners use #goodfire for wildlife and their habitats…

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe