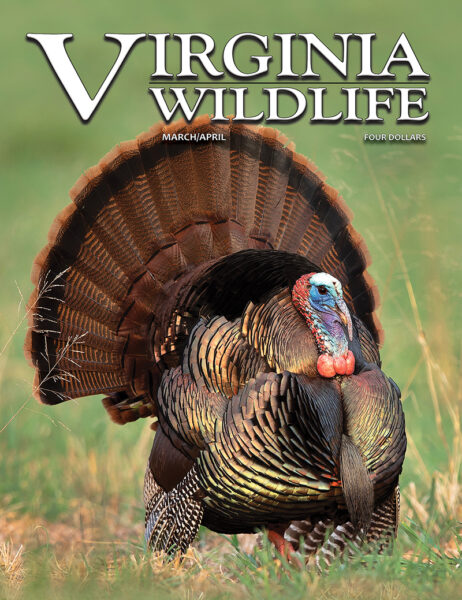

Once called the “golden swamp warbler,” this handsome neotropical migrant makes its annual flight from Central & South America to parts of Virginia in search of wetland breeding habitat.

By Mike Roberts

Photos by Mike Roberts

There are sounds of nature tucked into the minds of all naturalists which, upon reoccurrence, unspool the memory of the moment in time they were first heard.

One such personal memory occurred for me on a warm April morning nearly 40 years ago. Ernie Davis and I were anchored adjacent to a deep run in the scenic Staunton River lobbing bucktails to fat-bellied striped bass on their annual, 60-mile spawning journey. Above the noise of rushing waters, screaming reel drags, and occasional laughter, the cheerful notes of an avian’s song caught my ear. Twisting around on the seat of the flat-bottomed boat, I caught a flash of yellow in the overhanging sycamore and boxelder limbs. Then, as if scripted by Aldo Leopold, the colorful bird flew down to a twisting, wild grapevine just overhead and began chirping a most delightful ditty. This was my unforgettable introduction to the prothonotary warbler. There was no way to know it at the time but, many years later, the recollection of that neotropical migrant would initiate a new, exciting chapter of my personal environmental study.

Evolution of a Project

Brandon Martin, natural resource manager for Fort Pickett, right, and volunteer Phil Davis, strategize nesting box locations along tributaries of the Nottoway River in Brunswick and Dinwiddie counties.

In January 2017 it was my good fortune to accept employment through the Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation. Because of our lockstep interests in wildlife conservation, Ward and I had developed a meaningful friendship decades earlier. Soon after meeting the successful NASCAR driver, it became obvious his primary interest in life was natural resource stewardship. Through sustainable forestry practices, sound land-use decisions, and habitat enhancement, Burton’s organization dedicated itself to the welfare of the diverse community of plants and animals dependent on his foundation properties at the Cove.

During an early meeting, Ward instructed me to develop a project that could raise public awareness of the foundation’s objectives. My initial thought was to establish an interesting non-game project. So on a cold February morning, I set out to explore the Cove’s 2,500 contiguous acres bordering the Staunton River in rural Halifax County.

I knew we needed an extraordinarily interesting subject to attract attention; pulling on waders, I headed into the swamps. Although the day was blustery, the wetlands were teeming with wildlife. Flocks of woodies, mallards, and black ducks flushed from a beaver canal as I labored to push through the thick, underwater mats of smartweed. A red-shouldered hawk’s shrill call pierced the air, while a great blue heron in departing flight croaked disapproval at my intrusion. From the impenetrable tangles of leafless button bush, dried stalks of swamp rose mallow, and black willows, thoughts of that fishing trip and the little, yellow passerine emerged from my memory bank. If prothonotary warblers were using the Staunton River as a migration corridor, no doubt a pair nested here. The muddy margins of those Jurassic-like wetlands produced the concept of “Project Prothonotary.”

A Halifax County High School student sets up a press prior to drilling drain holes in a PVC nest bottom cap. Under teacher supervision, HCHS shop classes manufactured 50 of the project’s nesting boxes.

Researching ornithology in Southside Virginia, I soon discovered most people were not familiar with the prothonotary warbler. Prothonotary studies have been ongoing for decades in the lower James River and Tidewater, but breeding information in the Roanoke River basin was nonexistent. A handful of birders had recorded the species, but individual sightings seemed to be the extent of activity.

With no time to waste, materials were purchased, a half-dozen cedar boxes were constructed, and four sourwood tree cavities were collected from the forest. With assistance from several energetic youngsters—another vital component of the project—sites were selected and potential nesting facilities installed. By the end of March and right on schedule, everything was in place!

Science of the Matter

The prothonotary warbler (Protonotaria citrea) is a habitat-specific species preferring flooded timber with stagnant or slow-moving water. It is Virginia’s only warbler that nests in tree cavities. The majority of these gorgeous birds spend winter in Central and South America. Depending on where they overwinter, some round-trip migratory routes take them nearly 5,000 miles.

Clover Power Station employees Will Solomon, left, and Tim Hamlet erect a nesting box in company-owned wetlands adjacent to the Staunton River near Clover, Virginia.

The prothonotary’s North American geographic range includes parts of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas, from Wisconsin and Michigan south to the Gulf of Mexico, east to the Atlantic seaboard (excluding mountainous terrain), north to New Jersey and south to the Florida peninsula. Population strongholds are the Mississippi River drainage and swamplands in the eastern section of South Carolina. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists the species in the category of “least concern,” although historical numbers are suspected to be down in parts of its range by as much as 40 percent. The likely cause for decline is loss of wetland habitat and competition from other cavity nesters. In areas of the commonwealth where prothonotary populations have been monitored extensively, numbers are either stable or increasing.

As birds of perpetual motion, prothonotary warblers search thick, stream-side tree canopies for beetles, lacewings, crickets, caterpillars, small moths, and spiders. They also forage near the water’s surface and along floating logs for aquatic insects such as mayflies, stoneflies, caddisflies, damselflies, and the occasional terrestrial crustacean.

As with most members of the wood warbler family, the male prothonotary is first to arrive at a potential breeding location. With tireless vigor, he performs a repetitive chorus of “Sweet, sweet, sweet, sweet, sweet, sweet”—both to establish territorial parameters and to attract a mate. During this period he seeks out multiple nesting sites and garnishes each cavity with tidbits of moss. Upon arrival, and after pairing and mating, the female selects the preferred cavity to construct her nest of dried grasses, sedges, rootlets, moss, and willow leaves. The typical clutch of eggs is four to six, cream to pinkish-colored, highlighted with splotches of purplish-brown and gray. Incubation lasts approximately two weeks and is conducted solely by the female. Both adults participate in feeding the young that fledge 10 to 12 days after hatching. Nests are occasionally parasitized by brown-headed cowbirds; odd, because seldom do they target cavity nesters. Also unique to most warbler species, the prothonotary often produces two broods annually.

Jubilation Day

During 2018, Project Prothonotary used PVC nest boxes originally designed by Wisconsin DNR. Readily accepted by the birds, boxes were sponsored by individuals, organizations, and companies as seen on the name plate here.

With the approach of spring, prospects for the project’s success seemed somewhat dubious, primarily because the underlying concept was based upon suspicion rather than empirical proof. But upon my return to the wetlands in late April, all doubts were erased: The unmistakable song of a male prothonotary rang out loud and clear from the willows at the first site. In a matter of moments, the handsome songster flew to a dead limb within feet of where I stood mired in knee-deep muck to perform his sweet melody. No words can appropriately describe the jubilation I felt at that moment.

Three hundred yards farther upstream, a second male was singing. Even more exciting, through binoculars from 40 yards away I watched a female busily transporting nesting material into the cavity. Over the next two days it was my pleasure to discover five of the cedar boxes and two natural cavities in use. Even the vacant box had pieces of moss scattered over the bottom. Seven pairs of prothonotary warblers in wetlands stretching less than two miles: unbelievable!

Spring Semester

In a matter of a few short weeks, discovery transformed into a fantastic learning experience. It involved study of a range of interesting plants and animals that depend upon wetland conditions; suffering through the misery of stifling humidity, blood-thirsty leeches, and mosquitos; and yes, the inconvenience of spring floods. But the project turned out to be an exhilarating spring semester of outdoor education!

Time spent staring through a camera lens and binoculars validated much of the birds’ known behaviors. Yet there were several notable surprises, especially when the adults were feeding their young. For one, females approached nest sites in silence. Males, however, routinely flew to nearby perches to announce their presence with song. At the first note, the hatchlings automatically opened their bills! Also, it quickly became apparent that prothonotary warblers are effective hunters. Seldom did either adult return to the nest with a single food item. More often they transported multiple catches, especially when there were mayfly hatches. I observed the warblers’ bills packed with an assortment of food sources: spiders, mayflies, stoneflies, and caterpillars. Perhaps the biggest surprise of the entire project was the manner in which they tolerated my human presence. Still, on several occasions when I was caught standing outside the camouflaged blind, approaching males—like master ventriloquists—exhibited an uncanny ability to throw their songs, an adaptation to make them sound much farther away.

“The real jewel of my disease-ridden woodlot is the prothonotary warbler…The flash of gold-and-blue plumage amid the dank decay of the June woods is in itself proof that dead trees are transmuted into living animals, and vice versa.” — Aldo Leopold

Success! Five eggs found in one of the newly installed nest boxes.

Not one of the installed nesting boxes was adopted by other cavity nesters or flying squirrels. I attributed this to the fact that the facilities were purposely placed in late March after chickadees, nuthatches, and titmice had already selected nesting sites. To discourage use by tree swallows, the boxes were located in flooded areas with tree canopies. No nests were disrupted by snake or raccoon predation.

Although the project was established to determine presence of a unique migratory bird, it became a genuine lesson in land stewardship. For decades the Cove’s bottomlands had been heavily grazed by cattle, which resulted in soil erosion and habitat degradation. But with new ownership and a halt to agricultural practices, nature reclaimed the area under the supervision of a keystone species—the North American beaver. Bulging populations of the big rodent with superior engineering skills resulted in natural reclamation that benefitted numerous species of plants and animals, one of which was the prothonotary warbler.

Project Prothonotary 2018

The Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation made a decision to increase the project’s scope of activities in 2018. A design was adopted from the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, and 106 boxes were constructed and installed in portions of the Roanoke drainage (selected wetlands along the scenic Staunton River from Brookneal, downstream to Kerr Reservoir, up the Banister River, and the Dan River upstream of South Boston). In addition, 13 boxes were placed in wetlands along the Nottoway River within and adjacent to Fort Pickett in Dinwiddie and Brunswick counties. The objective was not a focus on propagation or collecting scientific data, but rather, expanding educational outreach in Southside Virginia about prothonotary warblers as ambassadors for a critical component of the larger environment.

Braving the chill of March and cold, inhospitable wetlands, a group of energetic youngsters surround conservationist Ward Burton while placing nest boxes for Project Prothonotary.

By the end of April a number of females had accepted the newly designed boxes, although heavy rains flooded several in low-lying areas. Then, during mid-May, and just as the warblers were in the middle of nest construction and egg laying, calamity struck. Over ten inches of torrential rain fell in the upper portion of the Banister, Dan, and Staunton rivers. Within hours, nearly 40 percent of the nesting boxes were several feet under water—silting nests and eggs. Yet the warblers showed resilience by adopting other boxes and, no doubt, natural cavities. By June, and exceeding all expectations, over 100 prothonotary warblers had been confirmed in close proximity to the selected nest sites.

Though purposely avoided by most people during warm weather, the inhospitable quagmires along the Roanoke River are treasure troves of flora and fauna. Thanks to the support of the Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation, we now have tangible evidence that far more golden swamp warblers spend their springs and summers here than anyone ever suspected!

For More Information

For More Information

Birding:

• • •

State and local agency partners included DWR, DCR, and the Halifax Soil and Water Conservation District. Box construction and installation assistance included students from Averett University, Halifax Co. High School, Hargrave Military Academy, employees of the Clover Power Station, and other volunteers. Financial support was provided by concerned individuals and businesses donating through the Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation’s Adopt-A-Box initiative and corporative partners Dominion Energy, Old Dominion Electric Cooperative, and Clover Power Station.

Article and photos © 2018 Mike Roberts. Mike Roberts is a lifelong naturalist and wildlife photographer who utilizes his knowledge of animal behavior and nature to educate others about respect and appreciation for the great outdoors.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe