By Louise Finger/DWR

Starting in the early 1600s and continuing well into the 1900s, tens of thousands of dams were built across the United States to harness the energy of moving water. That energy was used to mill grains, saw lumber, power foundries and forges for industrial metal production, facilitate transportation of people and goods up and down rivers through lock/dam/canal systems, supply water to communities, and generate early sources of electricity.

Most of these structures were low-head dams, defined as dams that span the full width of a river, are typically less than 15 feet tall, have water flowing across the entire crest of the dam, and do not provide flood-storage capacity.

Early dams were constructed of wood, then stone and mortar, and, eventually, concrete. At the peak of the low-head dam construction period, it’s estimated that there were thousands of these dams in Virginia alone. Though the effective lifespan of most of these dams was only about 80 years and many have since failed or are at risk of failure, thousands of them remain as obsolete structures in our rivers and streams.

“Why does this matter?” you might ask. Dams have significant impacts on the natural processes that occur in rivers because they block the channel, slow the water, alter the habitat, and degrade the water quality. Free-flowing rivers typically have areas of deep, slow-moving water that alternate with shallow, fast-moving water. In combination with sediment, vegetation, and other factors, these characteristics provide the complex variety of habitat for the different life stages of aquatic organisms such as insects, mussels, and fish. These features create appropriate ecological conditions to support native, riverine plants and animals.

The Drawbacks of Dams

By design, dams make the upstream water deeper and slower moving, which changes complex, river-like habitat into more uniform, lake-like habitat. This deep water essentially drowns what would otherwise be a diversity of shallower river features known as riffles, runs, and glides. As a result, the surface-water temperature goes up, dissolved oxygen goes down, evaporation rate increases, sediment settles out upstream, scour occurs downstream, and the nutrient cycle is disrupted. All of these changes affect the condition of the habitat upon which the native aquatic species depend.

Additionally, dams are physical barriers to aquatic organisms’ ability to move upstream, which creates a fragmented river system with isolated populations. These blockages inhibit, and often prohibit, the long-range migrations of fish species that spend part of their lifecycle in the ocean and part in freshwater. Dams also impact the movement of resident fish that spend their entire lifecycle in freshwater and the mussel species that rely on them.

To reproduce, mussels must attach their larvae (called glochidia) to the gills, fins, and body of certain fish species, relying on those fish “hosts” for dispersal of their young. If the host fish cannot travel upstream, then the mussel larvae cannot either. Freshwater mussels play a critical role in filtering water (as much as 18 gallons per mussel per day), thereby improving water quality, but many of these species are either extinct, threatened, endangered, or in decline. Though it is speculated that there are multiple causes of this decline in mussel diversity and abundance, historic proliferation of dams is likely one of the contributing factors.

Freshwater mussels benefit from barrier-free rivers. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

Humans are also directly impacted by the presence of low-head dams in our rivers because they are common drowning locations. Immediately downstream of such structures, the water recirculates strongly and results in a dangerous condition often referred to as a “roller.” At certain flow conditions, a roller makes it almost impossible for a boater or swimmer to escape. The calm, slow-moving water upstream of dams disguises this downstream risk.

Since no state or federal agency is charged with collecting data on drownings at low-head dams, the numbers are incomplete, but in the United States, there were at least 148 drownings at low-head dams between 2018 and 2021. In Virginia alone, there’ve been at least 19 such drownings since 1990, including two in 2022 at the Boshers Dam on the James River in Richmond. The public safety hazards and liability presented by dams limits the recreational opportunity and accessibility of our rivers by requiring portage by tubers, boaters, anglers, and other river users, which can lead to conflict with private landowners whose property is adjacent to dams located in navigable waters.

Restoring Habitat and Resilience

Removing dams has numerous and significant benefits. Dam removal restores the physical and chemical processes and, thus, the habitat that would naturally occur within that body of water. By eliminating what amounts to a wall in the river, the stream channel is allowed to adjust back to its pre-dammed width, depth, and gradient. As a result, the conditions that native species need in order to thrive are restored.

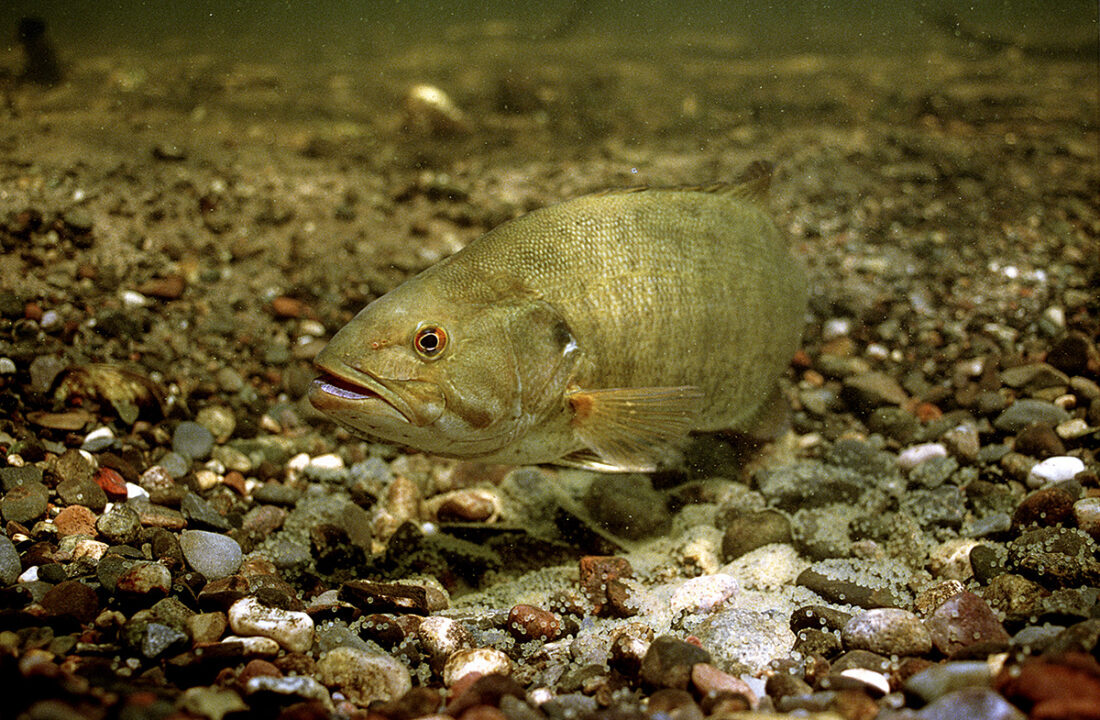

A few of the positive habitat outcomes of dam removal include the return of clean gravels for spawning; shallow, fast-moving features that oxygenate the water and provide ideal conditions for aquatic insects; and appropriately deep pools for cover and cool-water refuge. In addition, removing barriers to the movement of fish and wildlife decreases habitat fragmentation, which increases the resilience of all the species present in the river as climate conditions change.

Restoring free-flowing waters by dam removal helps create the clean gravel beds that fish species such as smallmouth bass need to spawn. Photo by Eric Engtbretson/Engbretson Underwater Photography

The extent of upstream and downstream benefits of a dam removal varies with structure size, stream gradient, and other factors, but the direct impact on the stream habitat and processes can be far reaching, often a mile or more. Depending on the proximity of other barriers, hundreds of upstream miles can be made accessible to fish and other aquatic organisms following a dam removal. Eliminating the public-safety hazard that low-head dams pose also increases the accessibility of rivers for safe, recreational use.

The Wilson Creek Dam in Bath County was a rock-and-mortar concrete dam constructed on U.S. Forest Service (USFS) land in the 1930s to provide water to Douthat Lake State Park, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps located in the park, and local residents. By the mid-1950s, the state park had installed wells for their water supply, but water from Wilson Creek Dam continued to be piped to downstream residents until a devastating flood in 1985. Obsolete for decades and structurally compromised, this nine-foot tall, 50-foot-long structure had significantly altered the creek’s slope, dimension, hydrology, ecology, and habitat for almost 100 years. Photo by Louise Finger/DWR

Upstream settling of bed material had buried the channel, downstream scour had removed gravels important for fish spawning, and passage of native brook trout and other resident fish had been completely blocked. In 2022, the USFS, in partnership with DWR and Trout Unlimited, removed the majority of this dam, while leaving a portion intact for historical interpretation. Photo by Louise Finger/DWR

The barrier was removed in an effort to restore the habitat and the appropriate channel conditions that allow for the natural movement of water, bed material, and aquatic organisms along this beautiful, coldwater mountain stream. Photo by Louise Finger/DWR

Removing obsolete dams restores streams for the benefit of all, and more of these structures are removed each year throughout the country. According to American Rivers, a nonprofit organization that promotes and tracks dam-removal projects, the number of dam removals completed annually across the country has been increasing since the early 2000s. Their database (at americanrivers.org) indicates that removals nationwide typically exceeded 70 per year since 2008, with a high of more than 110 dams removed in 2018.

Despite these efforts, thousands of obsolete dams remain. In Virginia, at least 46 dam removals have been documented through 2021; recent examples include the removals of Monumental Mills Dam and Wilson Creek Dam. Despite the multitude of benefits of removing low-head dams, their sheer number makes this endeavor challenging, but even more important, to undertake. Many of these dams are located on private property, and the removal process can be lengthy and cumbersome, so partnerships and collaboration are critical to removing them and restoring the rivers both humans and wildlife rely on and enjoy.

A lifelong resident of Albemarle County, Louise Finger has been working to restore aquatic habitats for 20 years in her “dream job” as DWR’s Stream Restoration Biologist.

Monumental Mills Dam

The Monumental Mills Dam, located on the Hazel River in Culpeper County, was a privately owned dam originally built of wood in the early 1800s to provide power to mill grain for flour and later rebuilt using rock and mortar as part of a planned lock and canal transportation system in the 1850s. In 1921, it was increased in height using concrete and con-verted to generate electricity. Though defunct since flooding in 1942, and in a state of significant disrepair, it remained a river-wide blockage to fish and other aquatic organisms, created a boating hazard for the public, caused upstream sedimentation and downstream scour, negatively impacted the complexity of in-stream habitat, and disrupted river hydraulics.

Monumental Mills Dam before removal. Photo by Louise Finger/DWR

This 10-foot tall, 160-foot-long structure not only impacted aquatic-organism movement, sediment transport, and water quality upstream and downstream in the Hazel River for close to 200 years, but also significantly impacted recreational use due to limited portage opportunity on surrounding private land. In partnership with the dam owner and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) National Fish Passage Program, and after significant historical review and documentation, DWR removed the majority of this structure in 2016.

Monumental Mills Dam during removal. Photo by Alan Weaver/DWR

The objectives were to restore the river’s hydrology and ecology, to remove a public-safety hazard, and to provide aquatic organisms access to 28 miles of the main-stem Hazel River and a total of 285 stream miles including the upstream, accessible tributaries. With the removal of Monumental Mills Dam, the Hazel River—down through the Rappahannock River and all the way to the Chesapeake Bay—is free of artificial barriers. DWR fish population monitoring four years prior to and three years after removal of Monumental Mills Dam showed post-removal passage of channel catfish and sea lamprey, two species that were not found upstream of the dam prior to removal. The presence of sea lamprey is especially notable as it is an anadromous species, meaning it lives in saltwater and spawns in freshwater. Paddlers and anglers are also now able to safely navigate and enjoy the beauty of this portion of the Hazel River.

Monumental Mills Dam site three years after removal. Photo by Louise Finger/DWR

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe