By Dan Bieker

It’s 7 a.m. on a chilly December morning and as I pull into his driveway, birding buddy David White comes limping out.

“How’s that sciatica?”

“Tolerable” he mutters. “Let’s go, we’re burnin’ daylight.”

So we’re off: two grizzled foot soldiers headed down the road with a truckload of kestrel nest boxes, two by fours, ladders, screw guns, hammers, and the smell of fresh coffee wafting through the cab. Today it’s just two of us, half of the Virginia Society of Ornithology’s (VSO) Kestrel Strike Force. Our mission: to erect as many nest boxes as we can before dark. If we’re lucky, maybe ten.

© Maslowski Productions

It’s all part of the VSO’s initiative to install nest boxes for the American kestrel (Falco sparverius sparverius) in suitable habitat throughout the state. No doubt about it, this little falcon is in trouble. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey—a massive data collection effort overseen by the U.S. Geological Survey—kestrel numbers in the U.S. have declined by half since the late 1960s.

We’re not naive; nest boxes alone will not save the kestrel. Reasons for their decline are many and not fully understood, but nest boxes can help boost populations where natural cavities are scarce. Other factors include a shift to more monoculture farming, competition from European starlings, and the ever-present threat from pesticides. The neonicotinoid family of insecticides is especially concerning, as evidence continues to mount on the harmful effects of these chemicals. “Neonics,” as they are called, can dramatically reduce the quantity and diversity of insects, and kestrels are voracious insect predators.

Luckily, the four-wheel-drive truck is up to the challenge as we slog through a slimy stew of mud and manure on an Orange County cattle farm, scanning for fence posts. Mounting boxes on fence posts avoids having to dig a hole and set a separate post (an unappealing proposition for us). Actually the box is attached to 12-foot, treated two by fours fastened into a ‘T’, then raised and screwed to a fence post. We can also place boxes on trees if they’re in open fields and have an unobscured trunk, or outbuildings if relatively free of human activity. The Strike Force endures mud, manure, barbed wire, ticks, chiggers, and livestock of questionable temperament, but we carry on!

At another stop, an interested but cautious farm lady worries kestrels will eat her cat. “No,” we explain, “they won’t eat your cat, your chickens, or your poodle. Kestrels are small, about the size of a blue jay, and eat mostly mice and voles as well as lots of insects.”

“Wonderful” she smiles in relief. “Have at it!”

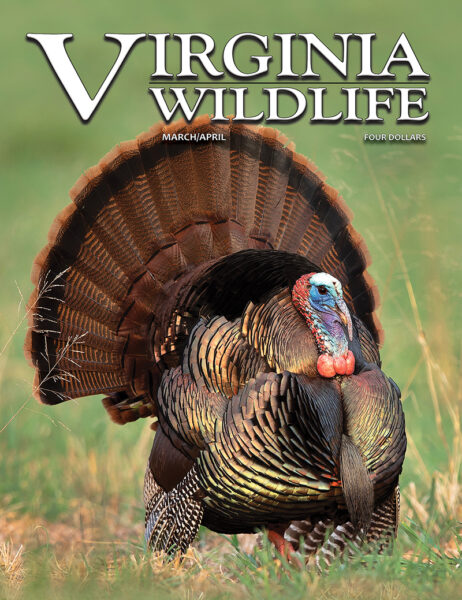

Primarily denizens of farmland, kestrels are the most colorful of all raptors, with males spouting striking blue-gray wings and females a rich, tawny brown all over. Like their cousin the peregrine falcon, kestrels are sleek, agile, and incredibly powerful for their size. Look for them patrolling over pastures or sitting patiently on utility wires, ready to pounce on whatever small critter lands in their sights. Besides small mammals and insects, they also prey upon lizards, frogs, snakes and—rarely—small birds.

Typically a male will scope out nesting sites during the winter, attempting to lure a female. As cavity nesters, kestrels are quite adaptive! They will nest in abandoned squirrel cavities, cracks in barns and other buildings, even high up in the metal pipe openings of electric transmission towers. Fortunately for our purposes, they take readily to nest boxes.

Our boxes are built with northern white cedar, which is incredibly light, durable, and weather resistant. Panels on the side allow access for cleaning and research purposes. Kestrels are quite messy, though it doesn’t seem to bother them much, and once a box is inhabited it tends to be used year after year. One box in a long-term VSO study was claimed 15 years in a row, with debris accumulating within inches of the entrance hole, and was still being successfully used. Kestrels do not build any nest inside their box; a few inches of added wood chips, however, affords some padding and helps nestle the eggs.

© Maslowski Productions

Three to five eggs are typically laid, starting in March or April. Kestrels are attentive parents, with each partner taking on specific roles. Most of the brooding is done by the female while the male brings food, especially closer to hatch time. Incubation takes about a month, and the chicks spend another month in the nest before fledging.

At our next stop, David spies a female kestrel atop the bare branches of a walnut tree. What better sign! It takes about 15 minutes to assemble the two by fours, attach the box and predator guard, and screw the assembly securely to a fence post. Sometime during the operation she has flown off. We can only hope she’ll return and take up residence before her primary nemesis appears.

Starlings! Those pesky, introduced freeloaders have disrupted so many of our native cavity nesters. One has to respect their tenacity, but on a practical level they spell trouble. “Skags,” as country folk are fond of calling them, will eat anything and nest in just about any hole. A kestrel can whip the tar out of a skag if it chooses, but once a starling has taken up residence in a box it’s less likely that a kestrel will do so. We’re not shy about informing landowners that it’s perfectly legal to ‘dispatch’ starlings at any time, or to at least remove the eggs and nest if they’re willing to access the box. Other species are more welcome, especially screech owls—since kestrel boxes are ideally suited to these diminutive raptors. Native bluebirds, flickers, red-headed woodpeckers, and tree swallows are also welcome inhabitants.

Kestrels are most definitely birds of open country, and the rural backroads of the Piedmont, Shenandoah Valley, and Allegheny Highlands are where most of Virginia’s kestrels reside. As old farmsteads (and farmers) gradually die away and development creeps farther into the countryside, kestrels and other species are being squeezed out. Their decline closely mirrors the demise of other open country and grassland species, such as bobwhite quail, upland sandpiper, grasshopper sparrow, and loggerhead shrike. While many factors are at play, habitat loss is major. Kestrels are also under attack from the air. Fledglings are especially vulnerable to Cooper’s hawks. For this reason it’s best not to place boxes along woodland edges, where Cooper’s hawks like to patrol.

Our next stop is a remote backroad cattle farm that even Google Maps apparently has not found. No fence posts here, so we scan for trees, settling on a lone standing poplar. After a few branches are pruned away I mount the box on my shoulder and shinny up the ladder, while my trusty cohort stands comfortably on terra firma barking out orders. “A little higher…more left…no!, more right!” It’s a juggling act, with one hand holding the box while fumbling with screws and a drill in the other. Funny how the wind blows twenty miles an hour faster and ten degrees colder fifteen feet up a ladder.

Keeping tabs on our more than 450 boxes scattered around the state is beyond the capability of the volunteer strike force, so landowners are encouraged to report on activity with their boxes. One monitoring project is ongoing, however, in Highland County, which hosts over 70 boxes. The effort is headed by local resident Patti Reum, who along with Mary Ames has been a dedicated strike force member since its inception. Using a wireless inspection camera that can peek into the boxes with minimal disturbance, Patti and other volunteers monitor boxes during the breeding season. Highland County is a stronghold for kestrels, with plenty of open country and livestock operations. Over 70 percent occupancy by kestrels has been observed in the boxes monitored there.

As natural nesting cavities become scarce and competition increases, the VSO’s nest box project will hopefully provide more opportunities for kestrels to raise their young. An equally important facet of the project is landowner education. Property owners are encouraged to preserve brushy areas, keep old fencerows in place, leave dead trees standing, and think hard about eliminating pesticide use.

Few birds possess the tenacity, fascinating antics, and colorful appearance of the American kestrel. An icon of American farmland, they symbolize our country’s rural heritage like no other species. Hopefully they will continue to be an integral part of our rural landscape, something our children and grandkids can continue to enjoy down the road.

Dan Bieker is an assistant professor of natural sciences at Piedmont VA Community College and vice president of the Virginia Society of Ornithology.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

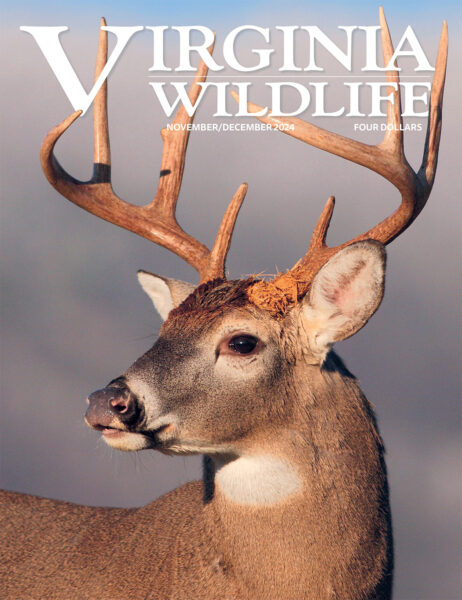

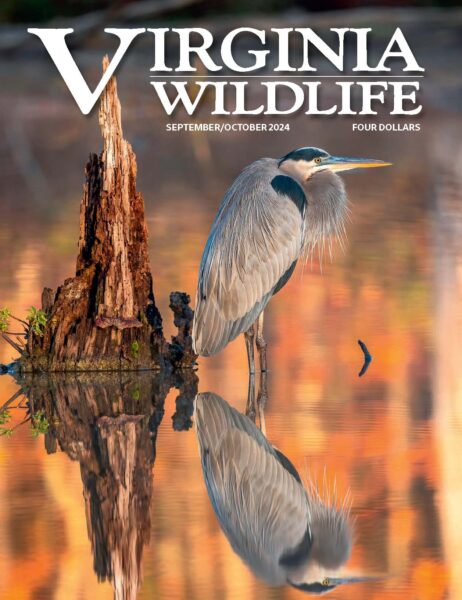

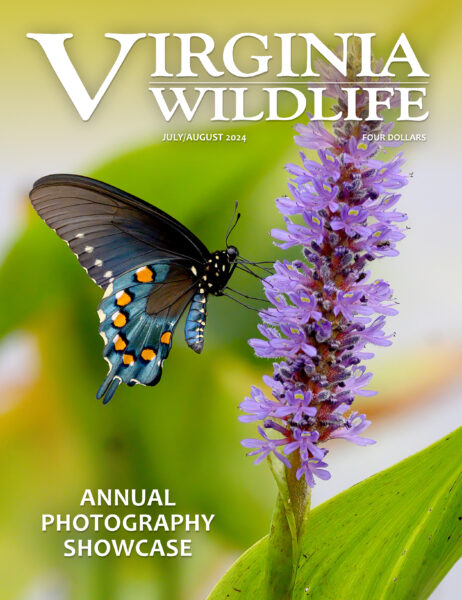

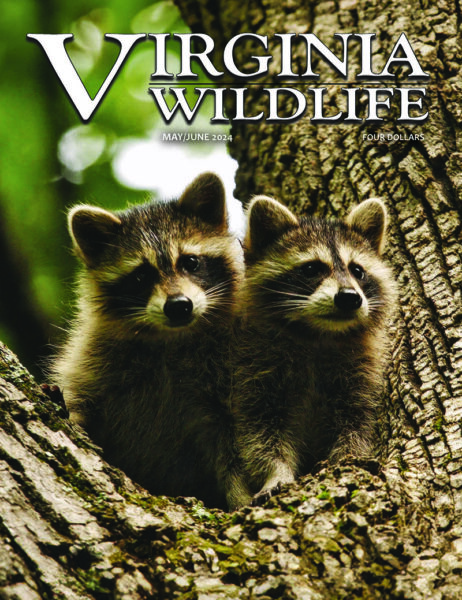

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe