Staff at DWR’s Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center are working to preserve a species on the brink of extinction.

By Ron Messina/DWR

An adult Appalachian monkeyface mussel. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

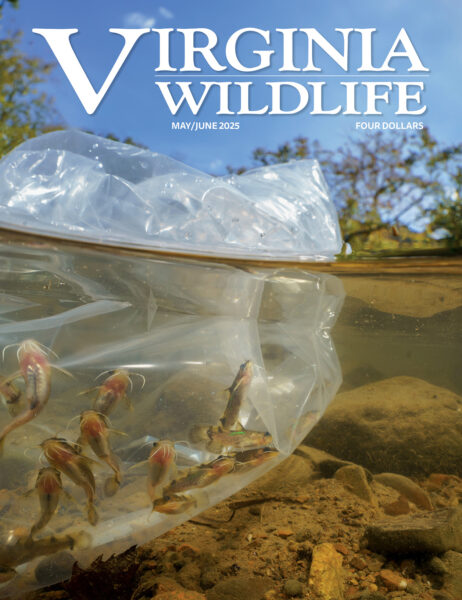

A hand plunges into the cool waters to place a marble-sized freshwater mussel firmly into the sandy, rocky, river cobble. Virginia’s Clinch River in Russell County is the site of the first stocking of the Appalachian monkeyface, Theliderma sparsa, one of the rarest creatures in the world. It’s a species that could wink into extinction if not for the efforts of the team assembled here on the water. The man who placed the mussel stands, dripping with water, as sunlight shines down on the remote valley, the winding river, and the life within.

“It’s a good day,” says Tim Lane, Southwest Virginia mussel recovery coordinator for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR). There was a lot packed into that simple statement—years of innovative research and painstaking work had gone into this historic mussel release. Specialists from various conservation groups working with him would agree, as each played a crucial role in this recovery effort.

Representatives from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) are here, shoulder to shoulder with DWR staff. Partners at the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), Virginia Tech, and nearby landowners have also provided support for the project. This mussel may be scarce, but it’s got a whole community of conservationists in its corner.

DWR’s media crew is here too, tripod set up in the river, capturing the historic moment with their cameras. “How rare is this mussel?” asks the cameraman. “It’s like a northern white rhino,” Lane replied.

A Last Chance

The Appalachian monkeyface mussel has been on the federal Endangered Species list since 1976. The earth’s last remaining population of the species exists only in one place—a 10- to 20-mile stretch of the nearby Powell River in Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee. It’s disappeared from other streams due to poor water quality and habitat destruction throughout the upper Tennessee River Basin. DWR’s mussel recovery team scoured the river bottom looking for them each spring for three years. After hundreds of hours searching, they could only locate eight, each one like finding the proverbial needle in a haystack.

This aerial photo shows the reach of the Clinch River in Russell County, Virginia, where the Appalachian monkeyface has been returned to the water. Photo by Ron Messina/DWR

They hoped they could take those eight mussels, only three of which were female, back to the lab at DWR’s Aquatic Wildlife Conservation Center (AWCC) to propagate them in a controlled setting as they have done successfully with other dwindling mussel species. The mussels could be then placed back into the wild, to give the species a much needed helping hand. Special permitting from USFWS to hold and study individuals of the species long-term was required, since the Endangered Species Act actually prohibits the capture and possession of endangered species, including the Appalachian monkeyface.

The AWCC, located at DWR’s Buller Fish Hatchery in Marion, is a compact but cutting-edge aquatic laboratory, bristling with tubes, rows of tanks, and jammed with specialized equipment to grow and monitor mussels. The modest facility has an amazing record of success in that endeavor.

DWR Mussel Recovery Coordinator Tim Lane inspects mussels being cultured in the floating upweller system (FLUPSY) located at the AWCC. Photo by Ryan Hagerty/USFWS

But there was a problem—the Appalachian monkeyface had never been cultivated in a lab, so there were unknowns around every corner. Scientists didn’t even know the mussel’s host fish. Some species of mussel use common gamefish like walleye or largemouth bass as hosts, others use catfish or tiny darters—but no one knew the host fish the Appalachian monkeyface needed for this early life stage. Without it, there could be no restoration effort. It fell upon DWR’s Mussel Recovery Biologist at the AWCC, Tiffany Leach, to figure it out.

“We tried over 40 fish species,” Leach said, but none were right. AWCC staff wondered if possibly monkeyface’s host fish no longer existed in these waters—in which case, the Appalachian monkeyface species was likely doomed.

Finally, the team tried a rare, four-inch minnow that’s seldom found in the Powell River. Leach soon noticed juvenile mussels, called “drop-offs,” on the tank’s bottom. The blotched chub turned out to be the host fish, and the key to the Appalachian monkeyface’s survival. The team focused on finding more blotched chubs to use as hosts, surveying local waters with electroshock gear, so they could pair them in tanks with the mussels. It was one big mystery solved, and one step forward in saving a mussel that had seldom ever been seen, and never yet cultured.

The blotched chub, host fish for the Appalachian monkeyface mussel. Photo by Hunter Greenway/DWR

“Every week they lived, it was new. No one had ever seen a [monkeyface mussel] at a month old, two months old, or a year old,” Leach recalled of watching the resulting juvenile mussels grow. “Every time I sampled them, it was something no one else had ever seen.”

Each day culturing them brought new discoveries, but even more questions. It took long hours at the office working weekends and holidays just to keep them alive—hacking nature, it turns out, is hard work.

Mussel Recovery Biologists Sarah Colletti and Tiffany Leach prepare fish hosts for glochidial inoculation. This process allows the glochidia to latch onto the gills of the fish, where after a short period they will drop off and be collected for culture by the AWCC staff. Photo by Tim Lane/DWR

“The main reason it took so long to get to this point is that the Appalachian monkeyface doesn’t have a straightforward propagation process,” said Lane. “Some mussel species, it’s like baking a cake for us—we know what to use and how to do it. This species, it felt like astrophysics. It was close to impossible to figure out how to produce them.”

While most mussels use a lure to entice a host fish, the Appalachian monkeyface didn’t. Biologists had problems figuring out what triggered its glochidia release until they just happened to observe a larval release in the captive mussels that was triggered by the vibrations of staff walking near their pan. “We just learned this recently, and biologists in the past wouldn’t have realized what was happening, but for sure they were disturbing them and triggering them to release the larvae in the process of collecting them,” Lane said.

Good News

From the eight they started with, the AWCC staff produced 165 Appalachian monkeyface mussels—enough to begin putting some back into Clinch River where they once lived. Of those, 125 were released and 40 were kept in captivity to support similar efforts in the future. Now, should some disaster strike the monkeyface population in the Powell, there will hopefully be a second brood stock surviving in the Clinch. A lot of thought and planning went into the selection of the site, beginning with confirmation that the host fish was present.

“We put them at what we feel is the safest place to put them in the state of Virginia,” Lane said of the Russell County location. “If they have a chance to thrive, this is the best chance humans can give them.”

The Clinch River holds an amazing 133 species of fish and 46 species of freshwater mussels, with more imperiled species—22—than any other river in the country. Its watershed sits in the middle of the Great Appalachian Valley, a vast, 1,200-mile trough running from Canada to Alabama. Its upper reaches are so pristine, and hold such abundant biodiversity, it’s been called “the temperate Amazon.”

“This river has the single highest density of imperiled aquatic species of any temperate river in the world,” said Braven Beaty, an ecologist with The Nature Conservancy. “It’s a special, special place. And it warrants our attention and our work to make sure that extends for the next generation and generations to come.”

Tim Lane (left) and Tiffany Leach (right) sort Appalachian monkeyface mussels selected for release into the Clinch River. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

On the occasion of the Appalachian monkeyface release, Lane took advantage of having an elite team on the water to do a river-bottom survey of previously stocked mussels. Surveys let researchers monitor the health of a population or even to track an individual mussel over time as it grows. This is Lane’s favorite part of his job, because it’s a glimpse into the mussel’s underwater world, allowing a real-time view of the overall vigor of mussels in the stream.

To conduct the survey, a biologist waves a detector wand along the river bottom to find the approximate location of mussels that have tiny passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags attached to their shells. Assistants called “searchers” float alongside in snorkel gear to pick out the tagged mussels so they can be examined, aged, measured, and safely returned to the river bottom.

Braven Beaty of The Nature Conservatory waves a detector wand along the river bottom to find the approximate location of mussels that have passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags attached to their shells. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

On this day, they found 15 different species of healthy mussels that staff from the AWCC had previously stocked, along with one big surprise—an untagged juvenile oyster mussel.

Just like the monkeyface, the oyster mussel is critically endangered. Finding a young oyster mussel here confirms that the thousands of previously stocked oyster mussels have now begun naturally reproducing successfully in this section of the river. That’s the long-term goal for the oyster mussel as well as the eventual hope for the Appalachian monkeyface—to begin new self-sustaining populations here in the Clinch.

The team of (from left) Tiffany Leach/DWR, Tim Lane/DWR, Braven Beaty/TNC, Sarah Colletti/DWR, Maddie Cogar/DWR, and Rose Agbalog/USFWS celebrated a “monumental” day for the AWCC after releasing Appalachian monkeyface mussels into the Clinch River. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

They Need Our Help

Mussels can live for up to 100 years, scuttling along the river bottom for short distances with a muscular “foot” they extend from their shell. They are filter feeders, consuming detritus and pollution from the river, with each capable of filtering about 10 gallons of water each day. Lane compares their importance and their function in the water to that of trees on land.

“Mussels are the forests of our fresh waters—just like you have a diverse, deciduous forest with oak trees and maple trees, the diversity of these mussels is important for the stream, because they all like different little niches out there in the river bottom,” Lane said. “They all have different fish hosts that come and go, so sometimes one species of mussel is doing well and having high recruitment and others aren’t; over time others will be doing well. Having all that diversity increases the community’s chance for persisting in the future.

“Mussels are important just like trees are to cleaning our air,” Lane continued. “They clean the water for all the fish, the salamanders, crayfish, and bugs. They’re starting at the base of the ecosystem, taking all the algae, bacteria, and detritus out of the water, fixing that to the bottom of the substrate, and making that energy available to the food web. Ultimately, humans are at the top of that food web and rely on them just as much as everything else.”

Lane says we all have a role in protecting these important creatures. Mussels are adept at filtering natural pollutants, but are extremely sensitive to man-made chemical pollution, like fertilizers and pesticides, and have experienced mass die-offs from contaminants humans have dumped into rivers over the years. Fortunately, the Clean Water Act of 1972 has made a big impact in preventing toxic discharge into our rivers. Property owners can do their part to help our rivers too, by keeping riparian buffers—stream banks—undeveloped and their livestock out of the river. When trees and plants near the water’s edge are removed, it causes erosion that chokes mussels in silt, creating a dead zone.

“They need our help. When we want to go fishing, swimming, or canoeing in a clean stream, we take for granted all that freshwater mussels are doing for us,” Lane said.

The rivers of Southwest Virginia are home to an incredible diversity of mussel species, including some of the most imperiled on Earth, and all need our protection. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

The team at AWCC has successfully cultured and stocked 35 different species of mussels to date, many with names as colorful as their distinctively patterned shells—rough rabbit’s foot, snuffbox, Cumberlandian combshell, birdwing pearlymussel, pink heelsplitter—and now, the Appalachian monkeyface. Lane says the imaginative names likely came from malacologists (mussel researchers) hundreds of years ago, working by candlelight, perhaps seeing a monkey’s profile or a bird’s wing in a shell.

Rose Agbalog, biologist with the UFWS, said that returning the Appalachian monkeyface mussel to the Clinch is “monumental. It’s a great step towards recovery of the species. Even though we have a long way to go, this is the first step in that direction.”

Lane said the day of the monkeyface release was the biggest day for the AWCC since it was founded in 1998. “I’m just very proud of the work my team has done, as well as the people who came before us, whose shoulders we’re standing on, who spent their whole careers trying to figure out how to recover species like the Appalachian monkeyface. They left behind all these little scraps of knowledge on how to produce them that we were able to piece together.”

The Appalachian monkeyface stocking on the Clinch has kick-started long-term goals for eventually producing tens of thousands more Appalachian monkeyface, as well as other endangered mussels and fish, and widening their range to nearby streams and tributaries.

“Hopefully one day, we’ll reach a point where this stream is functioning the way it should again, and we can focus on some of the nearby streams that aren’t as well off,” Lane said. “All these mussel species should be there as well, but they’re not. So we’d like to continue spreading this work we’re doing all over the Southwestern Virginia region.”

As the sun lowered on the horizon, the stocking team placed the last of the PIT-tagged mussels into the Clinch River’s stable bed of gravel and sand, where they can thrive and grow. The hard work is over for the day—the coolers are empty and the cameras packed away—but Lane and his team at the AWCC, and all their conservation partners, will return to their work of recovering species at the edge of extinction all over again in the morning.

Ron Messina is a passionate outdoorsman and the Video Production Manager at the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe