By Molly Kirk/DWR

The piping plover responds to perceived threats to its nest and young with a dramatic broken-wing display that aims to distract a predator away from its eggs and young. This strategy is effective when the threat is a fox or raccoon, but the danger now facing Virginia’s piping plover populations is much less identifiable, and one the broken-wing display can’t address alone.

A piping plover. Don Freiday/USFWS

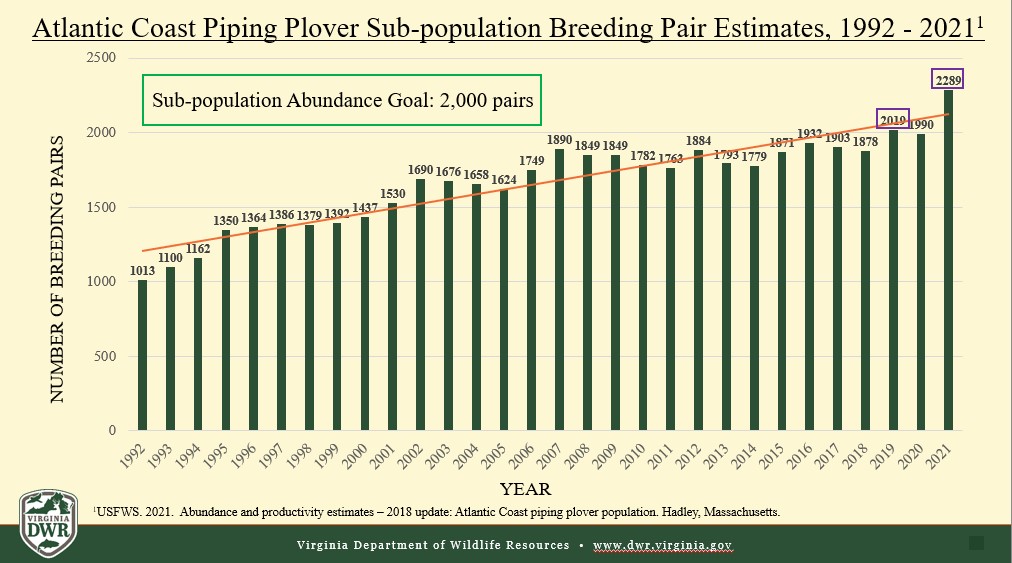

The Atlantic Coast piping plover (Charadrius melodus) population was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA or Act) in 1986. Plovers were harvested for their feathers by the millinery trade in the 1800s and early 1900s, which depleted their numbers significantly. The first regulation to appreciably benefit the piping plover was the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), which protected the species from “take,” which includes the pursuing, killing, capturing, selling, trading, and transporting of migratory birds. The MBTA also protects any bird parts, including feathers, eggs, and nests. Following the enactment of the MBTA, plover numbers rebounded until the mid-1900s, when increasing development and recreational use of nesting beaches became the predominant threats. The population embarked on another downward spiral, one that could not be reversed by the MBTA. It was not until the Atlantic Coast piping plovers came under the protection of the ESA, did their numbers start to slowly improve again.

As ground-nesting birds, piping plovers inhabit and nest on the broad, flat reaches of beach that are also popular with homeowners and tourists in coastal areas. The birds not only lost habitat, but also suffered casualties from foot and vehicular traffic on beaches that impacted their nests and well-camouflaged eggs and young. Their status as a threatened species allowed for greater protection of important nesting and wintering habitats all along the Eastern seaboard.

A piping plover nest on a barrier island beach. Photo by Lynda Richardson/DWR

The Commonwealth’s entire piping plover breeding population currently resides on remote barrier islands located on the seaward fringe of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, which are well-protected from development and most sources of human interaction. The Nature Conservancy (TNC), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) own the majority of the barrier islands and manage them for the benefit of wildlife and other natural resources. “We are very fortunate that we don’t have to deal with many of the issues that typically require the protections afforded by the ESA when it comes to conservation and management of endangered species in coastal habitats, such as development, unmanaged beach driving and other activities that can be extremely disruptive to nesting plovers,” said Ruth Boettcher, DWR’s coastal terrestrial biologist. “Having the barrier islands under protective ownership allows us to focus more on monitoring and managing plovers and less on managing people and minimizing human disturbance. That said, the ESA does allow us to implement time-of-year restrictions for activities that directly impact nesting birds and place provisions on other human activities that may affect nesting and/or foraging habitats. In states where a number of plovers nest on privately owned beaches, the implementation of these kinds of measures are a bit more challenging. Under these circumstances, the state wildlife agencies and the USFWS rely heavily on outreach efforts and cooperation from private landowners.”

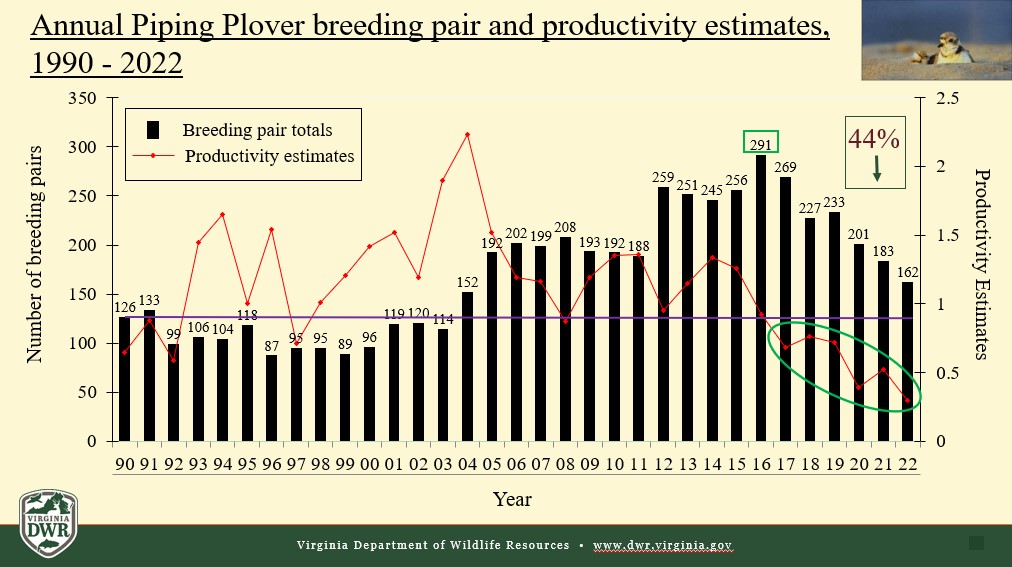

Virginia is part of Atlantic Coast piping plover population’s Southern Recovery Unit (SRU), which extends from Delaware to North Carolina. “Virginia supports the bulk of the nesting pairs within the SRU; unfortunately, our numbers have been tanking in the last six years. Virginia’s plovers have always done really well, so now we’re at a crossroads trying to figure out what is contributing to the decline in the breeding population,” said Boettcher.

Between 2000 and 2016, the population was either stable or increasing. Hurricane Isabel in 2003 created quite a bit of suitable habitat for the species, which resulted in incremental increases in the number of breeding pairs. “The population peaked in 2016 with 291 breeding pairs,” said Boettcher. “We thought we were well on our way to 300 pairs and another sustained bump in the population, but that was not the case. Between 2016 and now, the population has declined by 44 percent, accompanied by really low productivity. We’re not really sure what’s happening. Most of the islands are protected in perpetuity. They’re remote. It’s a best-case scenario for the birds, so we are at loss as to what is driving this downward trend.”

Boettcher noted some hypothesized causes for the decline: loss of suitable nesting habitat and reduced access to foraging areas due an of absence of significant hurricanes that normally scour the beaches and create washover fans on which plovers nest and provide unimpeded access to backside mudflats where chicks and adults feed. Other possible causes include avian predation, ghost crab predation, and overwash mortality (when storm or high-tide waters submerge nests or young). “We just started this season’s productivity monitoring and our numbers remain low,” she said. “We’ll see what happens this year with storms. Last year, we had storms early in the season that washed out a considerable number of nests, and the birds didn’t re-group like they used to; some simply abandoned their territories. That’s another puzzle to figure out.”

DWR’s Coastal Terrestrial Biologist, Roth Boettcher, at work on the barrier islands. Photo by Lynda Richardson/DWR

Piping plover populations in the New England Unit (Maine to Connecticut) are thriving, with that recovery unit exceeding the abundance goal set by the USFWS recovery plan in the last five years. In 2021, Massachusetts claimed 42 percent of the total Atlantic Coast piping plover population. And when looked at as a whole, the Atlantic Coast sub-population has been on the rise. But the abundance goal is set at 2,000 breeding pairs, so the margins are slim.

As the piping plovers gather and nest on Virginia’s barrier islands, Boettcher, along with TNC and USFWS partners, will be monitoring breeding productivity from April through mid-August, when the birds leave for their southern winter grounds. She’ll be trying to solve the puzzle of their apparent decline, and then, using the information gathered this season, work with partners to decide on which management strategies to implement that will help reverse the current downward trend.

“They’re special little shorebirds,” said Boettcher. “They’re part of the coastal ecosystem and indicators of the bigger picture. If they’re not doing well, then something’s wrong. High diversity is the sign of a healthy environment.”