By John (J.D.) Kleopfer/DWR & Jennifer Sevin, PhD

When someone mentions the illegal wildlife trade, it usually creates mental images of elephant tusks, rhino horns, or exotic animal hides. Most people would not think of turtles. However, tens of thousands of turtles and their eggs are illegally taken from the wild, or poached, every year to be sold on the black market for food, to be used in traditional medicines and religious ceremonies, or as products, souvenirs, and pets. It has become a global conservation crisis.

Turtles may seem slow and unimportant, but they are critical to the functioning of healthy terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) burrows, for instance, are used by more than 350 other species, while Northern diamond-backed terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) are believed to be a major source of seed dispersal for eelgrass (Zostera marina) in the lower Chesapeake Bay.

Unfortunately, turtles are now among the most critically threatened group of organisms globally. Due to their life history characteristics, including low egg and hatchling survival, delayed sexual maturity, and low reproductive output, poaching even a few adult turtles can devastate a small population.

Turtles are so heavily traded that many are regulated under the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), an international agreement between governments enacted in 1975. Under the CITES treaty, countries work together to regulate the international trade of animal and plant species and ensure that the trade is not detrimental to the survival of wild populations. Approximately 5,000 species of animals and 29,000 species of plants are afforded protection under CITES and are categorized under appendixes.

Although CITES is a step in the right direction in managing the wildlife trade, it does have its limitations. TRAFFIC (a leading non-governmental organization working on the trade in wild animals and plants) has highlighted a number of cases where wild-sourced animals have been fraudulently declared as captive-bred in order to make their international trade appear legal. In addition, the scale alone makes monitoring the trade difficult. From 1990 to 2010, approximately two million wild-caught turtles from 48 different species were traded around the world.

The Lacey Act of 1900 is the primary weapon in combatting the illegal trafficking of wildlife and plants in the United States. It prohibits the interstate trade in wildlife, fish, and plants that have been illegally taken, possessed, transported or sold. It protects these species by creating civil and criminal penalties for those who violate the rules and regulations. However, the General Accounting Office estimates that between $100 million and $250 million in illegal wildlife still cross U.S. borders each year in smuggled and fraudulently mismarked shipments, with turtles from the eastern United States being a part of this trade.

A Growing Problem

In 2019, law enforcement investigations in Florida, South Carolina, and New Jersey led to seizures of thousands of turtles. Although Virginia has not seen cases at the same magnitude as other eastern states, numerous cases have been made by Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) Conservation Police Officers.

In 2019, officials from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources seized more than 200 Eastern box turtles that had been illegally captured and were destined for international markets. Photo courtesy of South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

One of the more notable cases occurred in 2008 when 108 wood turtles (Glyptemys insculpta) were confiscated by DWR and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officers from a poacher leaving West Virginia. Unfortunately, this same individual pleaded guilty in 2019 to illegally capturing 140 wood turtles and transporting them across state lines into Florida with the intent to sell them. Although the punishment for violations has historically been minimal and not much of a deterrent, the judicial system is beginning to recognize the seriousness of these crimes and poachers are starting to receive significant sentences and fines.

Smuggled turtles are often taped to keep them immobile and from making noise while in transport. Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Another topic needing to be addressed is what happens to the confiscated turtles. Returning animals back to the wild is ideal. However, this presents a unique set of challenges, especially if the poachers are not forthcoming about where the animals were captured. Some people would argue that releasing the turtles into any suitable habitat within their native range seems like the next best logical thing to do, but mixing of genetics and the potential of introducing infectious diseases into the local population are among the concerns. In addition, adult turtles usually have well-defined home ranges and if released back into an unfamiliar area, their chances of survival are extremely low as they can struggle to find food and shelter.

Highway mortality can also be a problem as these animals attempt to cross busy roads in their quest to find their way back home. Ultimately their long-term care (which can be years) and associated expenses usually falls on state wildlife agencies and non-profit zoological facilities. Moreover, there is a lack of facilities, staffing, and resources to provide the care needed for the increasing numbers of confiscated wildlife.

Making Progress

Although the illegal turtle trade can be discouraging, not all is doom and gloom. In 2018, Virginia and other northeastern states began a regional initiative: the Collaborative to Combat the Illegal Trade in Turtles (CCITT). CCITT has recently merged with the Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Turtle Networking Team (PARC TNT) to work nationally. This grassroots working group is composed of state and federal biologists, wildlife law enforcement, legal professionals, academics, and members of non-governmental organizations.

The intent of this group is to advance efforts to better understand, prevent, and eliminate the illegal collection and trade of North America’s native turtles. A recent Call to Action letter from CCITT highlighting five priority needs was endorsed by 36 organizations and 655 conservation professionals. Those needs are as follows:

- Coordinate state regulations to help address current conservation risks to these species

- Provide additional resources for wildlife law enforcement to prevent collection and trafficking

- Enhance public outreach that communicates the severity and scale of the crisis and works towards eliminating national and international demand for wild-collected turtles

- Increase resources for emergency housing and care of confiscated turtles to relieve strain on law enforcement organizations

- Implement science-based planning to guide housing, care, and management outcomes for confiscated turtles

What Can You Do to Help?

Many people find turtles and other reptiles fascinating and seek only to observe or take photos of them. However, there are those who seek personal gain.

Except for snapping turtles that may be commercially harvested and sold with the appropriate permit, all native or naturalized species of turtles in Virginia are protected from commercial sale. Charging “adoption” or “rehoming” fees or any other form of barter is also unlawful.

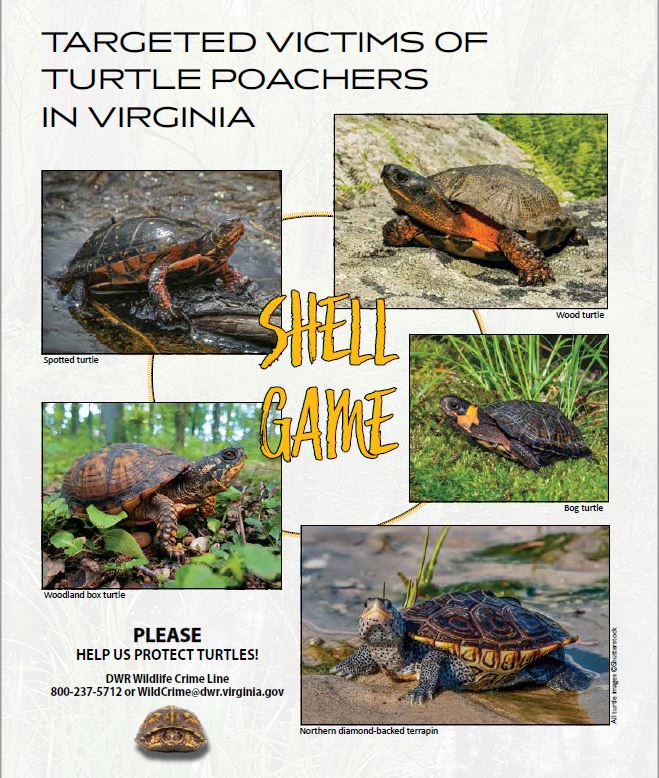

One best practice to follow while exploring outdoors is if you encounter a threatened or endangered species, or other species at risk of poaching, please do not post the location on social media. It’s not unheard of for poachers to use apps such as iNaturalist or HerpMapper to find animals. Turtles most threatened in Virginia from poaching include northern diamond-backed terrapin, wood turtle, spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), woodland box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina), and bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii).

If you are a landowner and someone seeks permission to access your property to look for reptiles, ask for identification and what they plan to do with the animals they find. Also, be cautious of individuals on state and federal lands who are carrying a bucket, pillow case, net, or other similar items that could be used to capture and hold animals. Carrying a snake hook or snake tongs on certain federal properties may be illegal, so check with the appropriate agency.

On Virginia’s Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs), it’s not illegal to carry these items, but it is illegal to collect or possess any species of reptile and amphibian from a WMA without a permit. If you see suspicious behavior and believe someone is illegally collecting, possessing and/or selling reptiles, please contact the DWR Wildlife Crime Line (1-800-237-5712 or WildCrime@dwr.virginia.gov). Because at the end of the day, the ultimate weapon in protecting Virginia’s wildlife and combatting the illegal turtle trade is YOU.

FIND OUT MORE !

To learn more about the illegal turtle trade and how you can help with turtle conservation visit: turtlesurvival.org.

For more information on Virginia’s turtles, you may obtain A Guide to the Turtles of Virginia at: GoOutdoorsVirginia.com.

For more information on Virginia’s wildlife regulations and how they pertain to turtles visit: virginiawildlife.gov.

John (J.D.) Kleopfer has served as the DWR State Herpetologist since 2005 and has written A Guide to the Frogs and Toads of Virginia, A Guide to the Turtles of Virginia, A Guide to the Snakes and Lizards of Virginia, and A Guide to the Salamanders of Virginia.

Dr. Jennifer Sevin is currently co-chair of the Collaborative to Combat the Illegal Trade in Turtles, co-investigator of the Network Exploring Wildlife Trade, and visiting lecturer at the University of Richmond.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe