A unique public/private partnership to remove a dam will restore aquatic habitats and have significant impacts on aquatic wildlife in Rock Island Creek.

By Molly Kirk/DWR

Photos by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

A slow trickle over the stones quickly escalated to a rush of water as the heavy equipment shattered rocks and mortar. A large bucket scraped the debris away, clearing a channel for the water to surge downstream, chattering and riffling over the rocks. As night fell and the machinery and people departed, adventurous fish nosed their way through the currents, marking paths upstream that had been blocked for hundreds of years.

Baber’s Mill Dam was built in 1827 to power a saw and grist mill on Rock Island Creek, a tributary to the James River in Buckingham County, and it had stood across the creek ever since. By the 2000s, it was six feet high and had been unused for decades. The dam created a pretty cascade of water but represented an ecological nightmare for the aquatic wildlife in the waters around it. By blocking any passage by fish and other aquatic wildlife to the 45 miles of waters above it, the dam marked a dead end from the James River upstream for a variety of migratory and resident aquatic species, including the sea lamprey and the endangered James spinymussel.

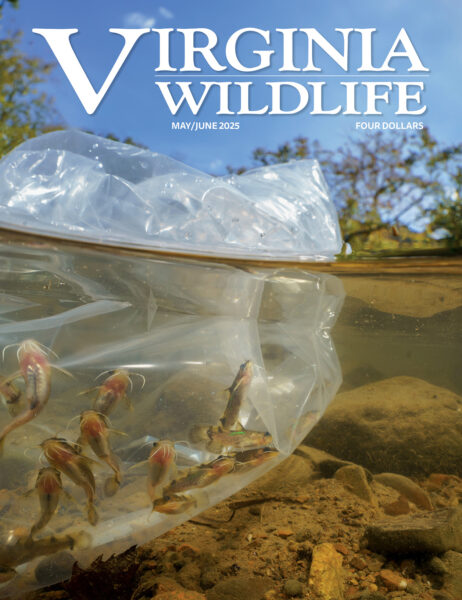

Baber’s Mill Dam before its removal.

But in April 2024, in a matter of just hours, the dam was gone, and the creek flowed without restriction as it had more than 200 years ago before the dam’s construction. “When I witness a dam being removed and the river being allowed to flow freely again, I truly feel the entire system breathing a sigh of relief,” said Louise Finger, the stream restoration biologist for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR).

Instant gratification isn’t a part of the vast majority of wildlife and fisheries biologists’ work. They’re usually monitoring populations over long periods of time and making habitat improvements that have long-term impacts on wildlife. The physical process of tearing down a dam is about as instantly impactful as a wildlife conservation strategy can be, instantly joining waterways that had been blocked for years and connecting aquatic habitats that had been isolated from each other.

“Dam removal is the best fish passage option for both migratory and resident species,” said Alan Weaver, DWR’s fish passage coordinator. “As a fisheries biologist, it is very rewarding to be part of a project that helps increase spawning and rearing habitat that will lead to both local and system wide ecological benefits.”

Finger started working on the process to remove Baber’s Mill Dam in 2022, after DWR’s State Malacologist Brian Watson had spotted the dam while doing mussel population surveys. The dam wasn’t recorded in any of the Virginia dam databases, so Weaver worked with The Nature Conservancy developer to update the Chesapeake Bay Fish Passage Prioritization Tool, an interactive map that evaluates and prioritizes dams and other in-stream barriers to aquatic organism passage to help inform aquatic connectivity restoration projects in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Baber’s Mill Dam ranked highly on the prioritization tool due to being accessible by diadromous fish (fish that migrate between salt and freshwater) and the amount of upstream habitat that would be reopened (45 miles of upstream functional network).

So, when a representative of Weyerhaeuser, the timber company that owned the dam and the property around it, contacted DWR a few months later, offering a partnership on removing the dam, Watson, Finger, and Weaver were all in. “We started the ball rolling in terms of how can we fund this? What’s it going to take to get it out? We started collecting data on the stream, talking to partner agencies, and putting together a proposal,” Finger said. An initial access agreement was developed, allowing for DWR to survey the dam and to begin aquatic studies.

Watson and Weaver conducted population studies on the fish and mussels below the dam, so they could know what species would benefit from the removal. Fish sampling was also done upstream of the dam to be able to monitor post-removal fish-community improvements. Weaver was excited to find spawning adult sea lamprey below the dam just prior to removal. Sea lamprey utilize the Bosher’s Dam vertical slot fishway at the upper end of the Piedmont to Coastal Plain fall zone on the James River each spring. After the dam removal, these native fish that migrate from saltwater to freshwater to spawn will be able to access the additional spawning and rearing habitat upstream in Rock Island Creek and its accessible tributaries.

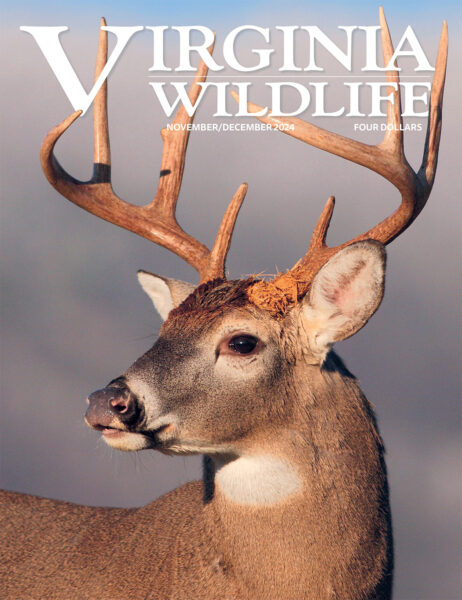

DWR Fish Passage Coordinator Alan Weaver holds a sea lamprey found near the base of Baber’s Mill Dam.

Watson and his staff had stocked propagated James spinymussel in the stream waters above the dam, and it was while monitoring the status of those stocked mussels that they found the dam. There were shells of stocked James spinymussel in the pool just above the dam, indicating that they had died after being washed into the pool. While sampling downstream of the dam in 2023 before its removal, wild James spinymussel were also found in Rock Island Creek between the dam and the James River.

Protected under the Federal Endangered Species Act in 1988, the James spinymussel has lost more than 90 percent of its range due to habitat loss and pollution. The mussel species hadn’t been found naturally in the mainstem James River for more than six decades. But in 2022, DWR stocked propagated James spinymussel into the James. Rock Island Creek is one of the few waters with a healthy wild population of the mussel. Mussels depend on host fish species during their reproduction, as the mussels’ larvae (glochidia) attaches temporarily to various host fishes’ gills to get transported upstream. “Removal of the dam will reconnect most of Rock Island Creek with the James River and allow James spinymussel to flow in both directions, hopefully strengthening the James spinymussel population in the area,” said Watson.

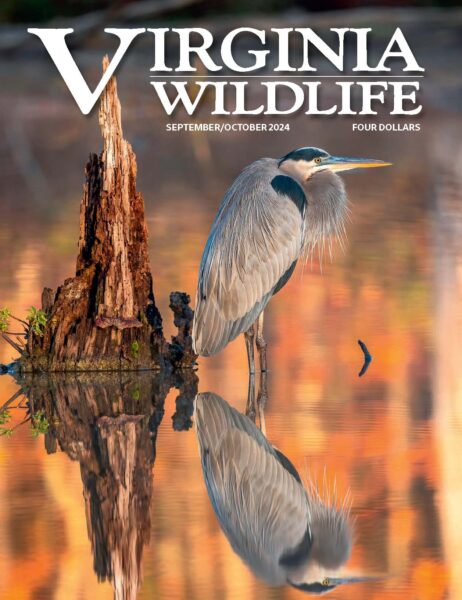

DWR State Malacologist Brian Watson with a James spinymussel found near Baber’s Mill Dam.

“Removal of the dam also eliminates the death trap the dam pool was for any adult mussels being washed downstream, and now these mussels can possibly settle out into suitable habitat downstream of the old dam location, and maybe even all the way into the James River.

“When we released propagated James spinymussel in Rock Island Creek and the James River, the longterm hope was that the populations would reconnect through natural reproduction and recruitment, and subsequent upstream and downstream movement,” Watson continued. “Unbeknownst to us, Baber’s Mill Dam stood between the release site and the river, blocking movement past the dam. Removal of the dam is a critical step in the potential recovery of this endangered mussel in Rock Island Creek and the James River.”

The dam removal project was a cooperative effort between DWR, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and Weyerhaeuser. Finger noted that it’s unusual for a property owner to contact DWR about removing a dam. “You don’t always have a willing landowner—the fact that they came to us is great. Long story short, Weyerhaeuser has been a great partner,” she said. “The fact that Weyerhaeuser has an aquatic ecologist on staff that is motivated and looking for ways to improve aquatic habitat on their land is wonderful. At every turn, they’ve been super easy to work with, collaborative, and motivated.”

“Weyerhaeuser was thrilled and grateful to be part of the team that carried out this project that is so important for the James spinymussel’s recovery efforts,” said Daniel Hanks, aquatic ecologist at Weyerhaeuser Company. “We pride ourselves on being good stewards of the lands we operate on. This project falls directly in line with our internal initiative to improve passage for aquatic organisms across our ownership. As an aquatic ecologist, it was personally an incredible experience to be able to participate in such a positive and tangible activity for conservation.”

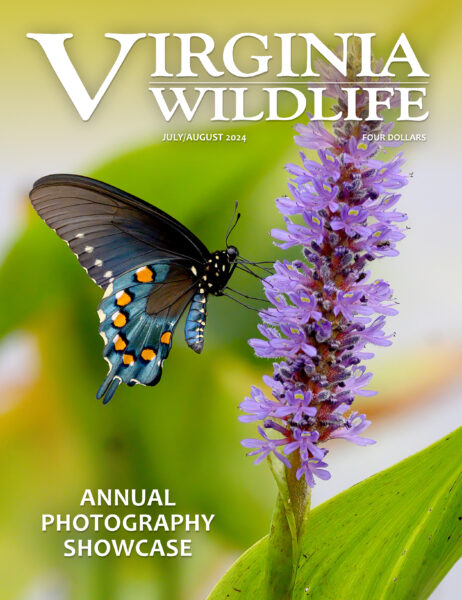

The Weyerhaeuser team worked together with DWR and USFWS to remove the Baber’s Mill Dam from their property.

Funding for the project came from several sources, including a USFWS State Wildlife Grant, a grant from a private foundation, and Weyerhaeuser. Because of the significance of the structure in the history of Buckingham County, an intensive architectural study was completed as part of the historic resources review process. So, though the dam is no longer standing, its history is now documented in both local and state archives. “This is a great example of a public/private partnership formed to plan, fund, and implement a significant ecological restoration project,” said Weaver.

Rock Island Creek’s waters now flow freely past the former Baber’s Mill Dam site.

In 2014, Virginia signed the multistate Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement (CBWA), which established goals for cleaner water, habitat restoration and conservation, improving fisheries, increasing public access, and environmental literacy. Part of the CBWA was a goal to reopen 1,000 miles of fish passage waters by 2025. “Baber’s Mill Dam’s removal is a substantial contribution to the goal and overall effort,” said Weaver. “It’s not just the mileage number, but also the significance of each individual project and the biological response that really matters.” The 1,000-mile goal has been met and exceeded by the end of 2024. And now, Baber’s Mill Dam is in the “removed dams” data layer of the Chesapeake Bay Fish Passage Prioritization Tool!

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe