By Tom Hampton/DWR

Photos by Meghan Marchetti/DWR

To say the Clinch River has shaped and enriched Rex Carter’s life would be a vast understatement. He’s spent most of his 77 years within a few miles of this Southwest Virginia waterway and his earliest memories include walking along the riverbank with his father. It was a very short walk from his childhood home in Clinchport.

Through the years, the Clinch River has delivered all the quintessential Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) activities for Carter and others—fishing, boating, hunting, trapping, and wildlife viewing. The available species changed, for the better in most cases. Deer, turkey, and bear populations rebounded to plentiful numbers during his lifetime. Bald eagles, golden eagles, and a host of other non-game species are frequently observed now.

Coyotes appeared on the landscape. Other species, like quail and grouse, all but vanished. There are fond childhood memories of his family fishing for “jack fish,” the old-timey, local name for walleye. And there are also heartbreaking memories of historic pollution events in the 1970s that devastated fish populations in the Clinch.

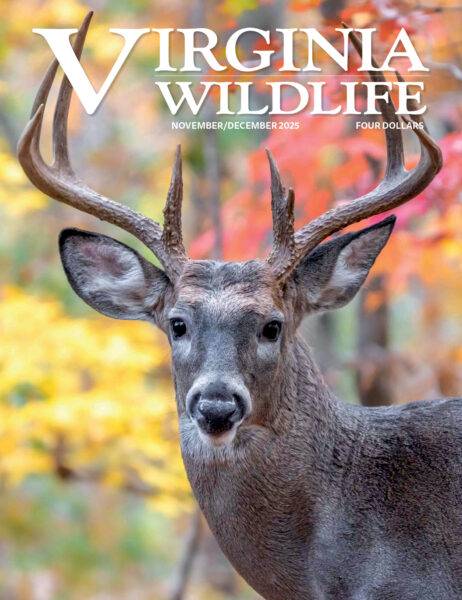

Carter, an avid deer, bear, and turkey hunter, started buying land at the age of 18. The farm that he and his wife Rena have assembled on the Clinch River is enrolled in DWR’s Deer Management Assistance Program (DMAP). For the past 15 years, they’ve managed doe numbers and passed on harvesting good bucks in favor of mature bucks.

Data submitted to the program offer ample proof of success. Jawbones submitted as part of the DMAP agreement indicate that the bucks harvested on the Carters’ property in recent years were at least 6 years old. The antler measurements and recorded body weights are impressive by any standard.

But Carter has also been thinking long-term with his land management. When he submitted his DMAP deer jawbones to DWR in 2017, he also delivered a proposal. He wanted to carve out a small portion of his land on the Clinch River for public access. Several potential buyers had previously expressed an interest in purchasing this parcel adjacent to the river. The offers were attractive, but Carter worried that a private sale would result in “someone placing a camper on the river and putting up ‘No Trespassing’ signs,” Carter said.

Rex (left) and Rena Carter made the generous decision to prioritize public access for outdoor recreation when selling the six-acre parcel that is now the Copper Creek Conservation Initiative.

He wanted the public to have access to the Clinch River, access that might allow them to enjoy some of the same experiences that had enriched his life. For state agencies, the land acquisition process is more of a marathon than a sprint. Initial efforts to establish public access on Carter’s property proved an uphill trudge. However, Carter and local DWR employees maintained an open dialogue and a common goal.

Over the course of several years, new opportunities were identified, and new decision-makers entered the equation. The original offering was expanded to include some adjacent land with extraordinary conservation value. DWR recently acquired a six-acre parcel of land dubbed the Copper Creek Conservation Initiative from the Carters that includes the confluence of Copper Creek and the Clinch River. The land fronting the Clinch River provides access for bank fishing and for hand launching of canoes, kayaks, and other paddlecraft at the Rexrena access site (named after Rex and Rena Carter). Bank fishing for a variety of species is particularly good here. The incoming flow from Copper Creek meets a substantial ledge in the Clinch River. Seasonally this creates unique hydrology, temperature, and water clarity conditions. Smallmouth bass, walleye, and sauger are a few of the sportfish species that congregate here to take advantage of foraging and resting conditions.

From a boating access perspective, the Rexrena site provides two float trip opportunities. Putting in at DWR’s Clinchport Boating Access site just upriver provides a short float trip of about 2½ miles downstream to Rexrena. Putting in at Rexrena, paddlers can float about 9½ miles downstream to the State Line access point. As the name implies, the takeout for this longer float is near the Tennessee state line.

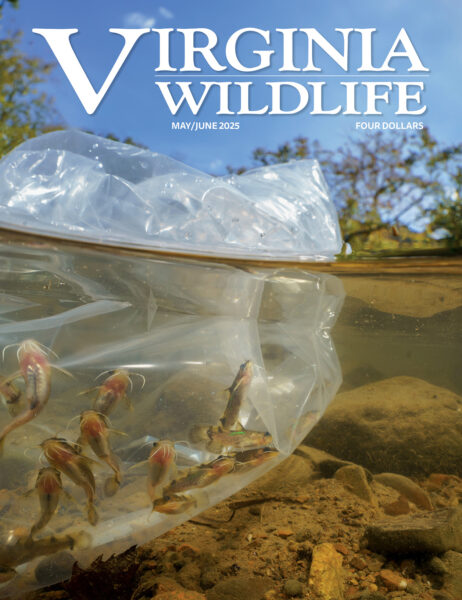

One quarter mile of Copper Creek frontage is the extraordinary conservation piece of this acquisition. Copper Creek served as a refuge for aquatic species during the historic pollution events that affected the Clinch River. Today, Copper Creek is home for 64 native fish species, including several that are listed as Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan. Copper Creek also provides habitat for more than a dozen mollusk species. Beyond critical habitats, the acquisition also secures access to longterm wildlife population monitoring sites utilized by DWR biologists and other researchers. It’s not a stretch to hope that some of the imperiled species found in Copper Creek may one day be propagated to restore populations in suitable habitats elsewhere in the Clinch River drainage.

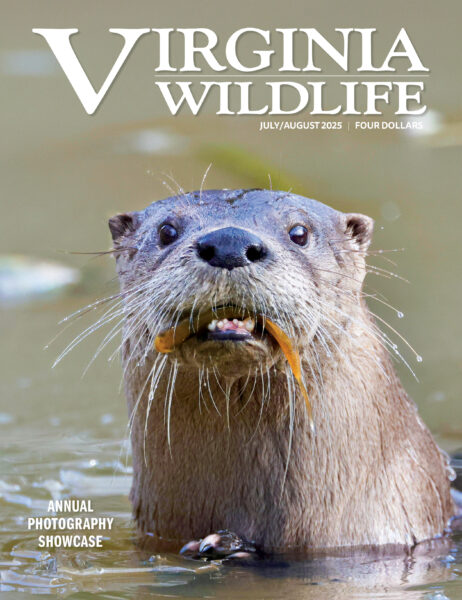

For wildlife viewers, the site is a treasure trove of possibilities. Downed trees provide plenty of perching opportunities for piscivorous birds such as belted kingfishers, green herons, and bald eagles. In spring, viewers can listen for the sweet, descending whistle of Louisiana waterthrush or go searching for one of the numerous warbler species that can be found flitting about the forested river edge. These riparian areas are important habitat for a host of terrestrial and avian wildlife species, but don’t overlook the aquatic wildlife viewing opportunities offered here as well. Shiners, darters, and other minnows display vibrant colors at certain times of the year. Longnose gar have fascinating physical features and habits (like gulping air). Mussels are next to impossible to see from above the water’s surface; they’re down there in the substrate, filtering water and doing their best to ensure the survival of the species and water quality.

History buffs will not be disappointed. An internet search for the Copper Creek Viaduct, Speers Ferry, and the Wilderness Road Crossing of the Clinch River is a great place to start. Some exposed concrete near the mouth of Copper Creek is all that’s left of a grist mill that once provided the life sustaining service of grinding field corn into meal that fed families and their livestock.

Securing this property is a big win for wildlife and wildlife enthusiasts. It’s a public access and conservation legacy made possible by a grant from the Virginia Land Conservation Fund, and the patience and generosity of Rex and Rena Carter. DWR is honored to be the new steward of this property, and proud to offer you another location to Explore the Wild.

Tom Hampton is the Region 3 lands and access manager for DWR.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe