The public land offerings in the Rapidan River area are rich with history and opportunities for fans of wild places.

By Serena Grant/DWR

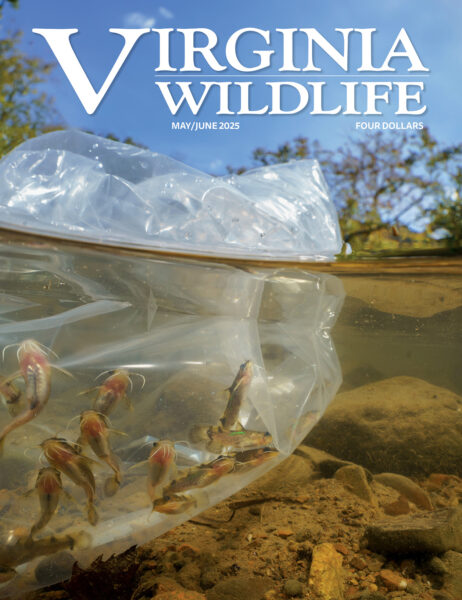

Fishing is a chance to wash one’s soul with pure air, with the rush of the brook, or with the shimmer of the sun on the blue water,” wrote former President Herbert Hoover in his 1963 book “Fishing for Fun and to Wash Your Soul.”

During his tenure as the 31st President of the United States, it was the Rapidan River that provided Hoover, an avid angler, that chance to escape Washington, D.C., and wash his soul as he navigated the challenges of leading the country. The area’s rich history and the river’s pristine trout waters have long been revered by historians and outdoorsmen alike. Whether you’re an angler, a hunter, or just enjoy being outdoors, the Rapidan River area—including both Shenandoah National Park and Rapidan Wildlife Management Area (WMA)—has something to offer you.

History on the Rapidan

Originally a small-town settlement, the Rapidan Camp site at the head of the Rapidan River is best known for its affiliation with Hoover. After Hoover won the presidential election in late 1928, he tasked his secretary, Lawrence Richey, with scouting sites for a presidential retreat, under the conditions that it included a trout stream, a minimum elevation of 2,500 feet, and a location within 100 miles of the capital.

William Carson, the chairman of the Virginia State Commission for Conservation and Development at the time, encouraged Hoover to consider the Rapidan River area based on its exceptional trout fishing. “The stocking of the streams is in the hands of the proper persons and is being attended to,” Carson wrote in a letter to the Hoovers.

President Herbert Hoover poses with a trout he caught on his fly rod. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

The Hoovers visited the Rapidan Camp site in January 1929 and agreed that its 164 acres on the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains suited their needs. Hoover was inaugurated in early March, and a local newspaper article dated March 22, 1929, announced the choice of the upper Rapidan location for a Presidential fishing lodge. It was the first retreat built specifically for presidential use and pre-dates the current presidential retreat, Camp David in Maryland. The Hoovers paid for the land purchase, construction supplies, and furnishings. Marines supplied the construction labor as part of training exercises.

Hoover’s wife, Lou Henry Hoover, led the design and construction effort at Rapidan Camp along with architect James Rippin and family friends. Upon its completion, the site included 13 buildings for staff and guests—all connected by a series of paths and bridges and designed to blend into the rustic mountain setting. The compound centered around the Brown House, which served as Hoover’s onsite White House. Other buildings included a Town Hall for meetings, a Mess Hall for meals, a duty station for the Secret Service, and up-scale cabin housing for secretaries and other workers.

Rapidan Camp proved to be the ideal getaway for noted outdoorsman Hoover. As he said, “No other organized joy has values comparable to the outdoor experience.” True to his ideals, Hoover spent his getaways there fishing and meeting informally with staff, international dignitaries, or constituents against the backdrop of the gorgeous Shenandoah site. The guest register included Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Mrs. Thomas Edison, the Edsel Fords, Henry Luce, and Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., along with British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. Presidential business continued while Hoover visited the camp, with mail and newspapers delivered daily via airplane drop.

After his loss in the 1932 presidential election, Hoover donated Rapidan Camp to the Commonwealth of Virginia, intending for it to be used by future presidents. Three years later, the site officially became a part of Shenandoah National Park, falling under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service (NPS). President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Rapidan Camp, but found it difficult to access, so he built Camp David in the Catoctin Mountain Park of Maryland.

The site was leased by the Boy Scouts of America from 1948 to 1958, after which the NPS tore down all structures except for three. The remaining buildings, which still stand to-day, are the Brown House, the Prime Minister (which housed MacDonald during his stay), and The Creel. Other manmade aspects, such as paths, bridges, and water features, are also still present.

Guests of the Hoovers gather at the Brown House. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

In November 2023, the Quaker Run wildfire on Shenandoah National Park and Rapidan WMA threatened the buildings of the Rapidan Camp, but federal, state, and local firefighters prioritized preserving the camp’s structures. They set up sprinkler systems and protective firebreaks to help keep the site intact. “Firefighters ran hose and sprinklers throughout Rapidan Camp,” said Madison Heiser of the NPS. “Sprinklers were fed by a pump system using a natural water source, and this gave firefighters access to plenty of water to protect Rapidan Camp. We’re grateful for everyone’s efforts to protect these historic structures.”

People interested in visiting the site to get a better idea of its history will be pleased to find the Brown House’s restoration and the Prime Minister’s conversion to a museum. Both are open to tours with rangers, and both exteriors are as they were built back in 1929.

The Brown House today, after restoration. Photo courtesy of NPS/Knepley

Beyond Hoover’s influence and memory, the site and its surrounding areas remain a staple for anglers, hunters, and other outdoor enthusiasts alike. Why is that so?

Casting Where Hoover Cast

Rapidan Camp is nestled within thousands of acres of public land, surrounded not only by Shenandoah National Park, but also by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ (DWR) Rapidan WMA. Rapidan WMA consists of 10,326 acres broken into eight separate tracts distributed along the east slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Madison and Greene counties. The Rapidan Tract of the WMA has the Rapidan River running through it and is close to Rapidan Camp.

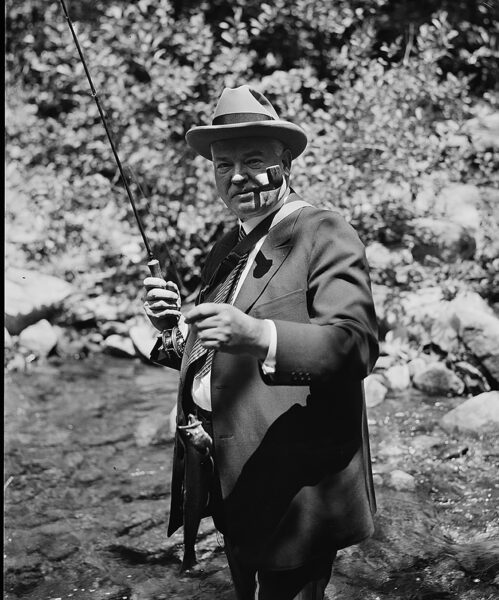

The Rapidan, Conway, and South rivers are the area’s major waterways and host an exceptional native trout fishery. Healthy populations of brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) abound in the WMA’s rivers and streams, especially the Rapidan and Conway. The Conway River also contains numerous wild brown trout (Salmo trutta) to entice the adventurous angler. Small, swift-flowing headwater streams grade into larger, boulder-adorned rivers. Cascading white water interspersed with shallow and deep quiet pools filled with native trout provide a wonderful experience for the trout angler.

The effort that the Rapidan requires of anglers, according to Steve Reeser, DWR regional fisheries manager, only adds to the appeal. “It’s not like you’re standing in the Madison River and you’ve got 40 feet of line out there, taking these long casts like Brad Pitt in ‘A River Runs Through It.’ You’re making short little casts and roll casts and hopping from rock to rock,” he said.

Native brook trout inhabit the Rapidan River, offering prized angling opportunities. Photo by Alex McCrickard/DWR

DWR began acquiring the Rapidan WMA land in the mid-1960s. According to DWR District Wildlife Biologist Joseph C. Ferdinandsen, “a lot of that land was likely settled and mirrored a lot of the things you found inside of Shenandoah National Park.” While the bulk of the land bought was either personally owned or the property of a timber company, the site has since been best known for its river and its population of native brook trout.

“It’s the only native salmonid species there. We don’t stock anything there on purpose,” said Alex McCrickard, DWR aquatic education coordinator. The native brook trout has evolved since the Ice Age to live in high-altitude, cool, and clear waters. They require silt-free, oxygen-rich water, which the Rapidan provides. The Rapidan’s most notable residents, the native brook trout, make it quite popular with anglers. The Rapidan’s brook trout average five to eight inches in length, how-ever, some of the deeper holes in the middle to lower reaches of the river can hold some 12”+ brookies. “The Rapidan is popular because it has such a strong native brook trout population—it’s a stronghold,” McCrickard said. The Rapidan River and its tributaries within Shenandoah National Park and Rapidan WMA are managed as a catch-and-release fishery, prioritizing the continuation of the trout population while still allowing the public to enjoy what they have to offer.

A Diversity of Wildlife and Opportunity

The WMA, however, is not just for anglers—Rapidan offers an array of opportunities for hunters as well. A moderate but stable deer population exists on the WMA, as well as turkey, gray squirrel, and ruffed grouse populations. While visiting Rapidan Camp in Shenandoah National Park, be sure to keep an eye out for woodcock as well.

While the WMA has the most to offer for anglers and hunters, there’s something there for everybody. The diversity in the Rapidan’s flora and fauna provides opportunity for wildlife watchers and nature photographers alike. “Rapidan is a forest and mountain WMA,” said Rapidan WMA Manager Jon Petri. “There is lots of [primitive] camping on the Rapidan and it’s a great way to get away and enjoy nature. Hunting bear and deer in the fall is the most popular activity. The spring and summer are filled with campers and anglers fishing for brook trout.” There is a network of hiking trails in the Rapidan Camp area of Shenandoah National Park.

The Rapidan River in typical springtime flows. Fun fact: the Rapidan River was originally called the Anne River, after Queen Anne of England. During seasons with frequent flooding, the streamflow would quicken, and people would refer to it as the “Rapid Anne.” This soon was shortened to the colloquial “Rapidan River.” Photo by Alex McCrickard/DWR

It’s no wonder that Hoover chose the Rapidan area as his getaway from the frantic, day-to-day rush of the White House. Ferdinandsen remarks that while the river is accessible, “it offers quite a bit of solitude.” Removed from the hustle and bustle, the beauty of the Rapidan is found in its scenery and wildlife inhabitants.

“It’s a very pretty area, especially in the spring,” McCrickard said, highlighting the stairstep pools and hemlocks hanging over the river, noting that the native brook trout found in that water “look like a painting. They’re just a beautiful little fish with pretty spots, patterns, and colors.”

“You get a sense of exploration,” Reeser said of the Rapidan area. “You get the white water tumbling over the rocks and getting aerated. It’s so clear.” What comes to mind when he hears the word “Rapidan” is “it sounds rapid, it sounds wild, it sounds pristine,” he said—all of which aptly describe the landmark.

As the DWR Creative Content Intern in the summer of 2023, Serena Grant got to participate in all aspects of magazine production. Serena has returned to college and is looking forward to a career in writing and publishing.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe