By John Page Williams

Photos by John Page Williams

Most of us see rivers while crossing bridges over them more often than we do exploring them in boats. From that perspective, the Mattaponi appears to be a narrow stream with wooded banks from busy roadways like I-95 (which crosses its headwaters, the Matta, Po, and Ni), or US Route 301 south of Bowling Green, or US Route 360 at Aylett.

Downriver at West Point, though, at the Route 33 Bridge, it’s big water opening to the even larger York River. True, there’s plenty to see upstream as well, but there’s actually a lot of maritime history on the lower river, as well as plenty of wildlife and three excellent Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) boat landings—West Point, Water Fence, and Melrose. We spent a day last spring exploring this part of the Mattaponi, launching at West Point and running 17 nautical miles up past the Mattaponi Indian Tribe’s Reservation before turning around and returning.

Looking down toward the York River from West Point.

West Point is a story by itself. A point of land where two strong, navigable rivers converge to create a third is a natural site for a town. Indians of what became the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes settled there around the year AD 1200. With oyster reefs and plenty of crabs just downriver in what we now call the York, broad marshes up the two tributaries full of waterfowl to trap and edible plants to forage, and plenty of fish (especially spring runs of shad, herring, white perch, striped bass/rockfish, and sturgeon), these Native people lived well.

When the Jamestown colonists came to Virginia in 1607, the point’s name was Cinquoteck, governed by Opechancanough, the warlike younger brother of the region’s Paramount Chief, Powhatan. Shortly after Powhatan’s death in 1618, Opechancanough became Paramount Chief and fought for years to expel the English invaders before his death in 1646. A treaty that year ended the open conflicts between Native Americans and English. The two tribes moved up their respective rivers to lands that in 1658 became their state reservations. Those reservations have formed the tribes’ homeplaces ever since. Despite significant hardships, they have carried on tribal traditions while adapting to and living successfully in the changing world outside.

In 1655, former colonial Virginia Governor John West established a plantation on the land that had served as Cinquoteck. In time, it became the settlement named for him as West Point, and in 1691, the Virginia General Assembly chartered it as a port of entry on the York. Its strategic position kept it active for more than 150 years, but it gained even more value with construction of the Richmond and York River Railroad in 1861. The railroad sustained major damage during the Civil War, but was rebuilt afterward, with what became a valuable connection to a steamboat line running up the Chesapeake to Baltimore.

In 1870, West Point became an incorporated town. Linked to Richmond by rail, it became a major shipping point for passenger and freight traffic until the early 1930s. Since then, West Point has been best known for its pulp mill on the Pamunkey side, which began to operate in 1914 and has remained the town’s dominant business ever since, still connected to Richmond by the rail link. Today the mill belongs to Smurfit-Stone Corporation, a division of Westrock, where it manufactures various paperboard products.

The Mattaponi side of West Point has served a variety of uses, ranging from steamboat wharves and an amusement park for tourists, complete with merry-go-round and roller coaster, to oyster houses serving watermen who tonged the beds nearby in the York. Just above the Route 33 Bridge, Glass Island held a shipyard and marine railway. Today, though, that site holds the excellent two-lane West Point launch ramp and fishing pier operated by DWR. It’s a great jumping-off point either for heading down into the York to fish the shell reefs for croakers, white perch, rockfish, and blue catfish, or for exploring upriver.

The Mattaponi is about a third of a mile wide here, but low flanking marshes mean the wind has a fetch of three-quarters of a mile, so there was a long history of sailing ships working their way up the river. The channel is deep, though narrow, and currents are strong in both directions. In fact, Walkerton, 25 miles upriver, has the highest average tide change in the entire Chesapeake system at 4 feet (5 feet on a full or new moon), so the current becomes either a good friend or a fierce opponent, depending on a mariner’s objective.

The Mattaponi saw plenty of shipping between the 1650s and the 1930s, with tobacco, grain, and lumber moving out and manufactured goods coming into upriver wharves at Aylett, Walkerton, King & Queen Courthouse, and various plantations in between. It’s no surprise that shipping moved slowly, working around current changes. Before internal combustion arrived for schooners’ yawl boats, a couple of stout crew members would row one to tow their schooner just fast enough to have steerage while the current was fair. When it turned against them, they tied their ship off to the bank or anchored until it turned fair again.

How 18th century captains negotiated the river the roughly 35 miles to Aylett is amazing. There are also remarkable stories of late 19th and early 20th century captains sailing schooners as long as 100 feet on fair currents through what was then a swing truss bridge on the Mattaponi side of West Point. That task took skills and daring that few skippers possess today!

Water Fence Landing

We thought about those watermen as we approached Water Fence Landing, about five miles above West Point on the King & Queen County (north) side. The DWR facility there is a single-lane concrete ramp with a pier and some parking spaces. It looked quiet that day, but a century ago, it was the site of the busy J.H. Coulbourn lumber mill. Another mile upstream, we passed Chelsea Plantation on the King William County (south) side, today a site for weddings and other gatherings but formerly an historic plantation, built in 1709 and lovingly cared for by a succession of owners ever since.

We saw a depth of 60 feet in the channel turn just below Chelsea. There are piles of ballast stones in the channel here offloaded by ships in Colonial times after voyages from England. The Mattaponi’s powerful current flowing through the channel’s looping meander bends gouges out these holes, while depositing sediment as the current slows on the insides of the curves. That sediment grows the broad marshes that have served the Mattaponi people well for centuries (along with modern-day waterfowlers).

The river still hosts runs of American and hickory shad, alewives, and bluebacks (river herring), though all of those runs except the hickories are greatly depleted. Stripers/rockfish still spawn in the Mattaponi, as do Atlantic sturgeon. Part of the reason for the river’s fish is the abundance of forage fish, especially gizzard (“mud”) shad, which also keep the Mattaponi’s plentiful bald eagles, ospreys, and great blue herons happy.

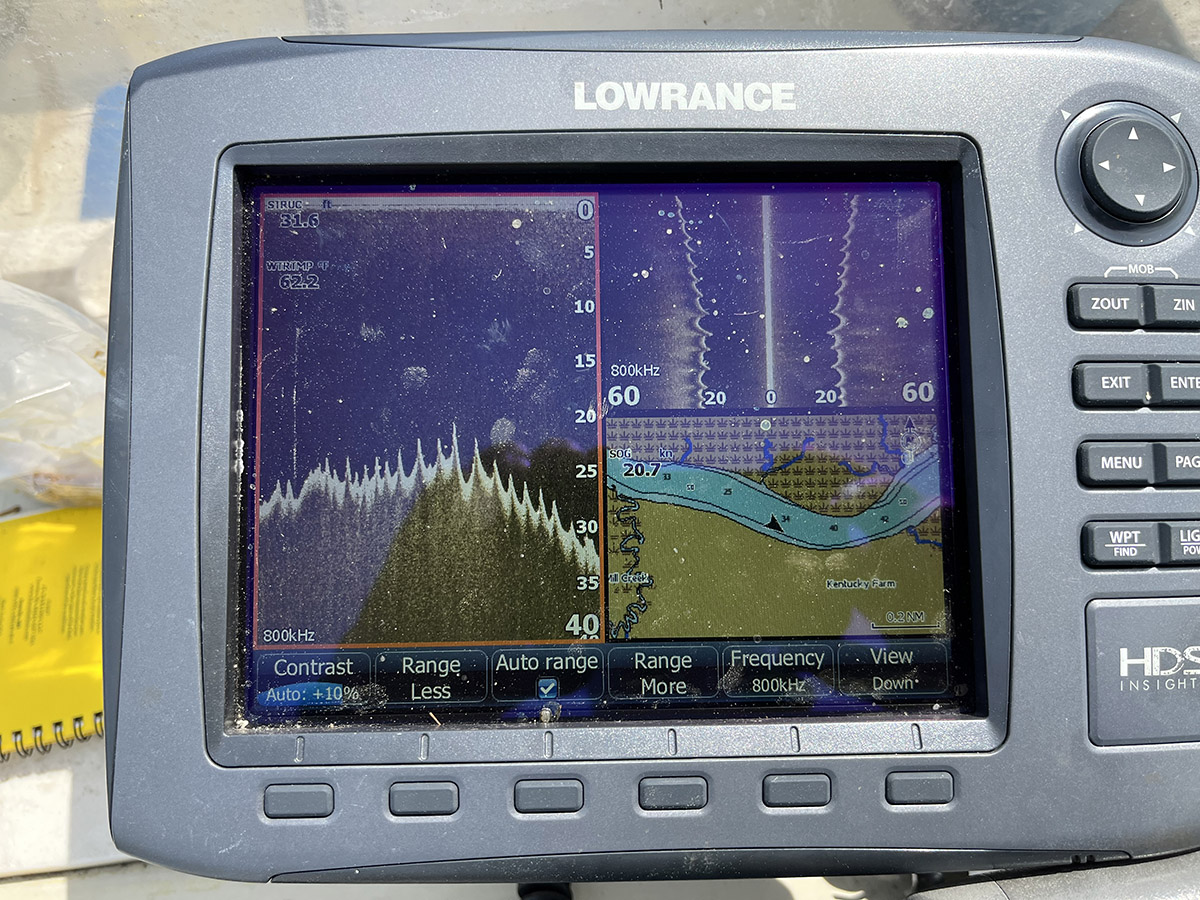

In a narrow turn 5 miles above Chelsea, we noticed a jagged pattern of hard sand in the Mattaponi’s bottom showing on our skiff’s sonar. It’s a pattern we actually first noticed in this river some 20 years earlier in the tight turn at White Bank, just above Walkerton, and which we have seen in a number of other high current areas of the James and Rappahannock.

The jagged river bottom patter in high current areas.

The actual furrows are more gradual than the image shows. They’re compressed on the sounder screen because the boat was running about 15 knots when the image showed. This powerful current keeps fish eggs in suspension, a characteristic that is especially important for survival of microscopic rockfish in their first days of life.

A mile and a half further up, we passed Melrose Landing, DWR’s second launch ramp on the King & Queen side of the river. It too is a single-lane concrete ramp with a pier and parking. In the broad reach of the river just above Melrose, we saw a big johnboat with two watermen aboard. They were setting a drift gill net with obvious skill.

Melrose Landing

Since all harvests of American shad and river herring are closed (and have been for some years), the only people allowed to fish for them are members of the Mattaponi Tribe, as subsistence harvesters under that long-time treaty. It was no surprise, then to recognize Todd Custalow at the johnboat’s tiller. Fifteen years earlier, I had watched with fascination as he and his father, then-Chief Carl Lone Eagle Custalow, set and fished another drift net upriver near Walkerton.

They are artists with these nets, carefully hung to ride the complex current seams in specific reaches of the river. We chatted briefly, with Todd expressing concern about the state of the shad and herring runs. The Mattaponi Tribe for many years has raised and released American shad at their Hatchery and Marine Science Center on the reservation’s riverbank, to give back to the waterway that has sustained their tribe for a millennium.

The Mattaponi Hatchery and Marine Science Center

We turned around just above the reservation and reluctantly headed home after a 17-mile run, according to the odometer on the skiff’s GPS. We had been fighting a head current, so the change in direction made the skiff’s passage feel almost like flight. Running back over the same stretch of river always presents an opportunity to fix the sights of the first leg firmly in memory. Upstream, the Mattaponi is magical, but the lower reaches are wonderful too. It’s a good thing that the Department of Wildlife Resources provides us with such good access to them.

John Page Williams is a noted writer, angler, educator, naturalist, and conservationist. In more than 40 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Virginia native John Page championed the Bay’s causes and educated countless people about its history and biology.