CPOs often face long hours and harsh weather to do a job they love

By Tee Clarkson

Photos by Meghan Marchetti

Tyler Bumgarner had been up and working for two hours before we met at six at the King and Queen County courthouse on the opening day of general firearms season for deer. For a Conservation Police Officer like Bumgarner, well, days don’t usually get much busier than this. Not only was this the opening of firearms for deer, it was also the first weekend of waterfowl season. I was along for the ride, aiming to get a sense of what a day in the life of a Conservation Police Officer (CPO) is like.

We would start by checking waterfowl hunters, Bumgarner decided, as we loaded up his boat at the courthouse and drove fifteen minutes to a ramp on the Mattaponi River. We waited for shooting time from the end of the dock as the marsh across the river began to take shape in the morning light. It was a few minutes later when the first knot of ducks appeared from the north, banking into the wind and turning toward a group of hunters in a blind tucked back against the trees.

A lone highball sounded from the call of one of the hunters. The ducks circled and dropped into the marsh, just not close enough for a shot. Duck hunters know that more often than not, if the day is going to be made, it happens within the first twenty minutes of shooting time.

Bumgarner, a waterfowl hunter himself, understands this full well. We waited on the dock another ten minutes before firing up the motor and heading upriver, passing by that first group of hunters so as not to interrupt the opening minutes of their morning.

“I try to look at what I do from a hunter’s perspective,” Bumgarner said, “and give people the same courtesy I would want as a hunter.”

Bumgarner joined the Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) as a Conservation Police Officer straight out of Bridgewater College where he graduated with a biology degree. At 32 years old, he has been on the job 11 years.

“I didn’t want to push paper,” Bumgarner explained over the whine of the motor. “I wanted to do something to make a difference, to promote hunting and fishing, to help protect the resource for other people.”

Bumgarner doesn’t have a whole lot of dull moments at work, especially on opening day. I learned that quickly. As we stopped the boat to glass a few blinds upstream, we could hear a pack of beagles running a deer less than a mile away. A few bends upriver a group of hunters unloaded on a flock of decoying ducks or geese.

Sunrise was still fifteen minutes off. Bumgarner hit the throttle and we continued on.

Bumgarner began his career as a CPO on the Northern Neck, where he worked for six years. He has spent the last five years assigned to King and Queen, but also covers King William, Essex, Middlesex, Gloucester, and Mathews counties. During hunting season, he might work half his weekly hours over the weekend, getting up before four and staying out until the last of the hunters are back at their clubs or homes. He will have only one weekend off a month.

“A lot of people consider this a job, but it’s really a lifestyle,” Bumgarner said, noting that while it is not necessary to be a hunter and fisherman to be a CPO, it certainly helps.

He pulled out his phone and showed me a photo of his young daughter standing on a dock with a two-pound catfish dangling from the end of her line. We both smiled.

An hour into the morning, we pulled into a creek off the main river where we had spotted four hunters in a floating blind. We were no more than 100 yards away when three shots rang out. I hit the deck on the bow. Clearly they hadn’t seen us. I searched the sky around the blind for birds, but there were none.

Something seemed off. Decoys were floating along the edge of the creek in no discernable pattern and well out of range of the hunters. It was getting toward high tide and clearly they didn’t have enough decoy string to hold in the creek.

As we pulled alongside, I noticed both the boat and the blind were brand new, as were the guns, the decoys, and pretty much everything the hunters had with them. The three shots, those were apparently fired into the sky to show a young boy with the group how to swing the gun and shoot at birds, an expensive lesson, I noted, based on the box of Black Cloud shells that lay open on the seat between them.

Bumgarner checked licenses, boat registration, and guns. The group had everything in order. They were down from Northern Virginia. This was their first time in the area and one of the first times they had been out duck hunting.

It was good to see new hunters in the field, even if they did still have a few things to learn.

After checking several more groups of waterfowlers, Bumgarner decided to turn his attention to the ground and to deer hunters. King and Queen County is less than 30 miles northeast of Richmond at its closest point. It is one of the more rural counties in the area, boasting a higher population in the late 1700s than it did in the census of 2010. It might not be too much of a stretch to say there are probably more deer dogs in King and Queen than people. At least it sounded that way on opening morning.

Within minutes of dropping the boat, the first call came over the radio. Someone had reported a hunter trespassing in Bumgarner’s region. The problem…it would take 30 minutes to get to the location. Bumgarner navigated his way through the back roads, but by the time we arrived on scene, there was no one around. The trespassing had apparently occurred on the border of two separate hunt clubs, one that runs dogs and one that does not.

As we sat parked on the dirt, several hunters approached in a truck. They stopped up the road. Bumgarner pulled up alongside, checked their licenses, and let them know what was going on, making sure they knew the call had come through.

“The way I see it, I am the referee out here,” Bumgarner related upon getting back in the truck. Much of his work during the season will be settling issues between different groups of hunters or between hunters and other landowners.

Over the course of the morning the calls were consistent, mostly trespassing. Bumgarner checked more than a dozen hunters’ licenses. All were doing what they were supposed to be doing.

“Ninety-nine percent of the people are great,” Bumgarner noted, “maybe one percent is a problem.”

A CPO’s vehicle serves as a mobile office, with access to license information and other records.

Around 10 A.M. we found ourselves on a back road where several hunters were set up along the edge of a field, hoping a dog would push a deer their way. We slowed, approaching the first of the group. Bumgarner stopped the vehicle and got out to check the hunter’s license. I leaned on the side of the truck. Something seemed different, as the hunter refused to make eye contact and shifted his weight awkwardly from side to side.

Bumgarner ran his license, then whispered to me to get back in the truck without a making a scene. Something was up. The hunter had recently been charged with several felonies, and there he stood not ten feet away with a shotgun loaded with buckshot. I was nervous.

It is of course illegal for a felon to be in possession of a firearm. Bumgarner made a call to run his record. We stayed in the vehicle and kept an eye on the hunter as he faced the woods in the opposite direction. As it turned out the felony charges had been dismissed, so technically he wasn’t doing anything wrong. Bumgarner returned his license and we were on our way. I breathed a sigh of relief.

Part of what makes the job of a CPO so dangerous is their many encounters with individuals holding loaded weapons. Just a few days later, Bumgarner would be called to an altercation between a landowner and another hunter. This time the hunter would be charged with three felonies and three misdemeanors, including a felon in possession of a firearm.

Backtracking up the county, we stopped at Scott’s Store—a local institution in Walkerton—for lunch. Bumgarner chatted with the owner. Outside in the parking lot he caught up with a few hunters in the area that he knew.

“Other law enforcement is more re-active. This is more pro-active,” Bumgarner explained, stressing the importance of building relationships in his line of work. it takes to get to know the lay of the land, to get to know the landowners, the different hunt clubs, the hunters in the area, and the amount of ground that each CPO is required to cover.

My day ended at 2 P.M. but Bumgarner still had several more hours to go. He would be out until dark, maybe later. The next day would be the same. Over the next several months, he and more than 155 CPOs will spend countless hours in the fields and forests and waters across Virginia, each one making a difference for our outdoor heritage.

Do you have what it takes?

Before becoming a Conservation Police Officer, recruits must receive all of the training associated with traditional law enforcement as well as specialized instruction for conservation law enforcement. This elite training includes tactical man tracking, fresh- and saltwater fish identification, and safe boating operations.

The Department is currently in the final stage of hiring recruits for the 10th Conservation Police Academy Class. This class of 25 officers will consist of new personnel and prior-sworn police officer transferees. The class is furthering the academy’s mission of recruiting, training, and retaining a full staff of 184 law enforcement professionals statewide. A rigorous program will thoroughly train the recruits to excel in their new careers as CPOs. The academy will include an emphasis on professional demeanor, policing in a diverse community, and achieving success through teamwork. In September 2018, just in time for hunting season, the new recruits will be graduated and sworn CPOs in field training.

From the recruiters to the training cadres, the Virginia Conservation Police Academy is continuing its high standard of excellence in training. The academy continually seeks the most qualified and diverse personnel to comprise the ranks of the Virginia Conservation Police.

Please contact our recruiters if you are interested in this exciting career: (804) 367-DGIF (3443) or recruiter@dwr.virginia.gov.

CPO Medina checks a fisherman’s license along the banks of Happy Creek in Front Royal.

Article © 2018 Tee Clarkson.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

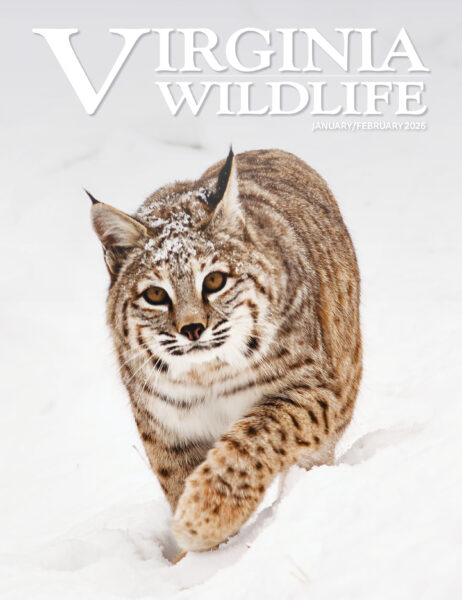

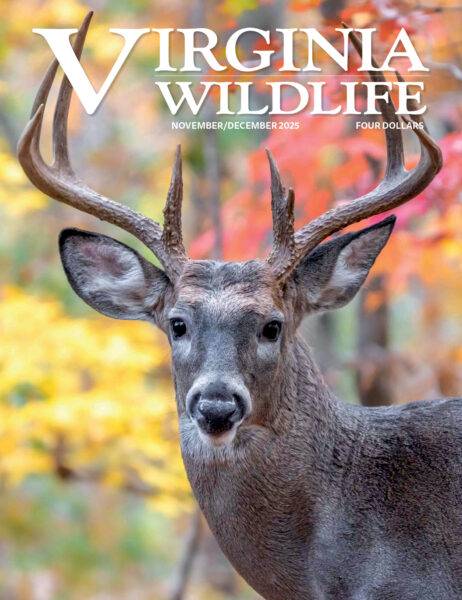

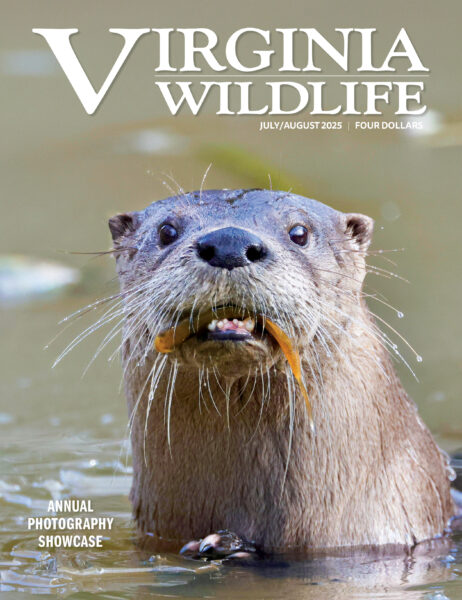

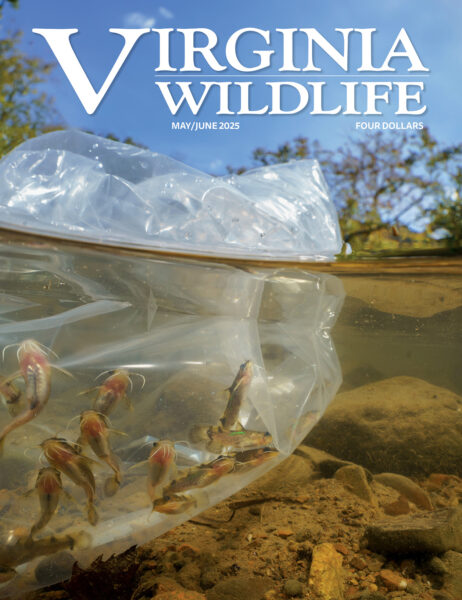

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe