A noted chef explains how his perspective on food shifted when he started hunting.

By Wade Troung

My fridge is a disaster. Despite my best efforts, there’s usually some dried blood caked to the glass shelves, and depending on the season, also a whole or mostly whole animal on one of the shelves that would usually be home to the orange juice or leftovers. The usual suspects in a home refrigerator are all there—condiments, eggs, cheese, and a drawer full of greens—but scales, feathers, and fur are equally the norm.

While I understand that having a few whole ducks in the fridge isn’t typical, I couldn’t imagine anything different at this point in my life. I’ve spent a career in the restaurant industry, from the time I was 12, when my parents opened a restaurant, to just a couple of years ago when I was an executive chef. For more than two decades, I spent more time in a restaurant than in my own home. In that time, I’ve learned more about food than I thought possible, eaten well outside of my pay grade, and tried foods that most people will never get to try. I prepared multiple lifetimes worth of food and learned how to cook with extreme efficiency, but more than anything else, I learned about how people interact with their food.

Twenty-plus years of watching people eat is how I would best describe my career. I learned how emotional eating is. Food tastes better when you’re in a good mood, and angry people don’t enjoy their meals. Some people love trying new things, but most are scared of not liking their meal. Guests love seeing exotic and rare ingredients on menus, but the burger is the most ordered menu item in America. We love eating because it brings us comfort, joy, and satisfaction.

But somehow, food processing is considered explicit content on many media channels. As a society, we don’t like being reminded of the costs of the food we love. I’ve been asked to debone steaks, take the heads off of shrimp and lobster, remove skin and bone, rename, rebrand, and hide what foods are in the name of consumer demand. Wild-caught, sustainable, organic, free-range, green—they’re marketing terms that drive sales, and they come from a good place, but there is still a disconnect with the food itself.

Smoked goose, day lilies, cucumber, arugula, and pickled fava beans make for a delicious gourmet meal.

Food with a Story

The reality is, many people would be disgusted with the state of my refrigerator because they don’t like being reminded that food involves death. Whether it’s a plant, fish, bird, or mammal, all of our food was once alive. That idea—that all food comes from death—was a concept that I didn’t fully explore until I started hunting.

In my mid-20s, I was a food and wine snob, which was ironic because I was plenty broke. The most interesting part of my job was trying new foods, and I learned that the best foods usually came with a story. Farmers, watermen, and artisan makers always had the best stuff. They weren’t just delivering ingredients, they were sharing their experiences.

They told me about good seasons and bad ones, sacrifices and triumphs, windfalls and failures. I was enamored with their stories, and I loved their food. I craved the emotions tied to the flavors. It made me realize that there is so much more to taste than what your mouth tells you, and it’s beyond what you see and what you smell. It’s how you feel, and how food makes you feel.

I wanted my food to have a story, so I started hunting. I taught myself how to hunt whitetails—it was a steep learning curve without a mentor, but I found success after dozens of cold days in a tree stand. My first deer tasted different from any food I’ve ever eaten. I was familiar with venison, but this was mine. It tasted like a frosty morning in the hardwoods, the sensation of warm blood on cold finger tips, the sound of dry twigs snapping, the smell of sweat from dragging the deer up a steep hill.

Wade Truong processes a deer during a workshop on processing wild game.

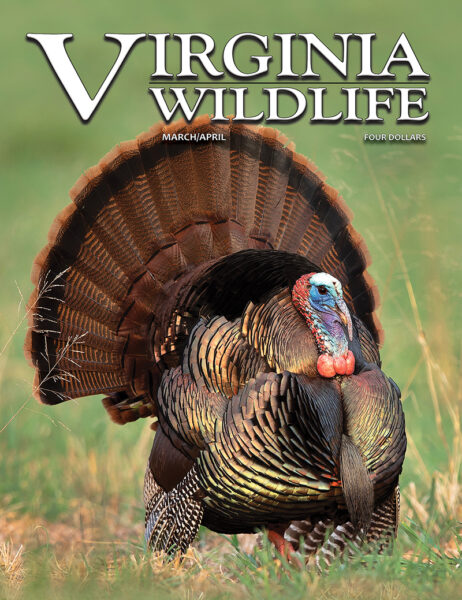

The meals that deer provided changed my perspective on food forever. I became increasingly obsessed with procuring my own food. I started expanding my hunting season, my larder, and my experiences. Bow hunting gave me a few extra weeks in the deer woods, ducks and geese showed me the beauty of a predawn marsh and taught me to respect cold water. Squirrel hunting humbled me, doves made me a better shot, turkeys taught me that anything that can go wrong probably will.

I started fishing more, gardening and foraging, exploring places I didn’t know existed, learning about things I never thought about before. I learned that inconvenient places and times are the most beautiful, and how difficult it is to grow vegetables. I know the raw power of a green cobia, the ability of a morel to disappear, and the fleeting, ephemeral nature of the soft shell crab. I realized why we crave fat, salt and sugar, tender meat, smoke, and fire. I learned how to preserve food with heat, pressure, salt, and acid (there should really be a monument dedicated to celebrating modern refrigeration).

Cooking wild food made me a better cook. Wild plants and animals are inconsistent. Season, habitat, and the individual all influence the taste of wild foods. They’re products of their environment, they have terroir, and they are best treated as such. Their size, shape, fat content, and density differ from the domestic types vastly—you can’t cook a wood duck the same way you could a Peking, or smoke deer ribs the way you would pork ribs. And the more wild ingredients I learned to cook, the more I understood cooking as a whole.

The inconsistency and nature of wild food also gave me a new appreciation for scarcity. I couldn’t just get as much as I wanted, so I had to make what I had last. This taught me to make the most of every animal I killed. I learned how to cook tough cuts, and how to utilize bones, fat, and organs.

And while wild food can be inconsistent, it makes up for it in variety. At any given time, I have 20 species of animals in the freezer, not counting fish. Good luck finding more than half a dozen in a grocery store. This variability in food is the antithesis of my previous career in food, where ingredients were expected to be exactly the same, every time. I realized that our desire for consistency in our food has robbed it of flavor, and the reliability of domestic food has made us less tolerant of variety.

I’ve eaten ducks shot out of the same flock that varied in taste from “corn fed” to “low tide.” We judge beef steaks on their tenderness, not flavor, because they all kind of taste the same.

One of many dishes prepared with venison—black pepper-crusted venison roast with chimichurri.

Feeding My Soul

I now spend my entire year chasing food around. To be clear, I don’t save any money doing this. It would be cheaper and easier to buy all my food, but it doesn’t taste the same. It doesn’t feel the same, and it doesn’t nourish me the same way. Vegetables from my garden taste sweeter, the fish I catch taste fresher, and wild meats have more depth of flavor. These flavors come at the additional cost of bites, scars, and discomfort.

I’ve never been as cold as I’ve been duck hunting, or sweat as much as an August day poling down a creek. I’ve never had to check for ticks after a run to the grocery store, or had to navigate a storm on the bay to eat at a restaurant. These experiences have made me appreciate the luxuries I used to take for granted—reliable refrigeration, fast delivery, shelf-stable food. Summoning a hot meal from an app and having it delivered to your door is a modern marvel. Having access to food grown hundreds or thousands of miles away is a luxury, having it delivered to your door in two days or less is a miracle. Modern food processing has made calories cheap, consistent, and easy to chew. Feeding yourself is easier than ever, nourishing your soul is harder.

Cooking food that he’s sourced in the wild has changed the way Wade Troung approached cooking. Here, Rachel Owen, Wade Truong’s partner, poses with a spring turkey she harvested.

I started hunting and pursuing wild food because I wanted to taste new food and explore the emotional aspect of flavor, but what I found was that I was exploring my own needs. What these pursuits have given me is a sense of purpose I never had, and a connectedness to the natural world that I didn’t know was possible.

Like every other species out there, we have to consume. It’s the way life works—life eats life. I’ve chosen to live as close to this reality as I can. I like my hands dirty, my food clean, and I want every meal to remind me of what it takes to fulfill my basic needs. The macabre fridge is just a byproduct of my choices.

Every now and then, I think back to my life before I started pursuing wild foods, and laugh at how much it has changed my life and shifted my priorities. I spend my money acquiring experiences instead of goods, I care less and less about how people view me and the things I own, and more and more about my place in the world and how I view myself in it. These pursuits have taught me that I may not have everything I want, but nature has everything I need.

Wade Truong is a lifelong Virginian and self-taught chef and hunter whose work has been featured in The New York Times and Garden & Gun. To learn more about Wade and his company: Elevated Wild.

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

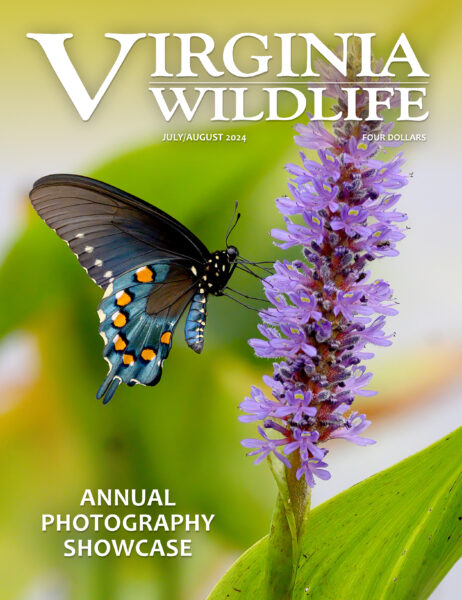

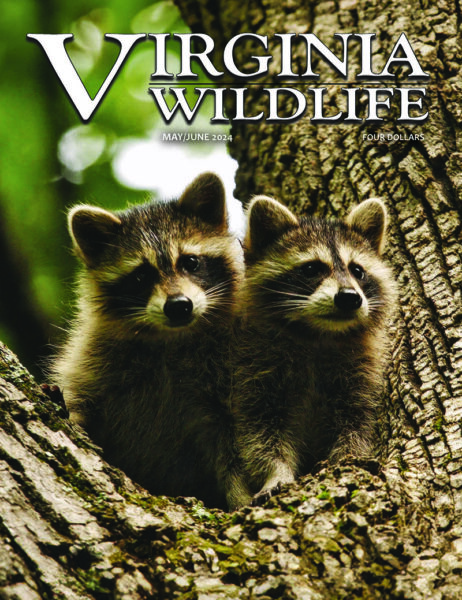

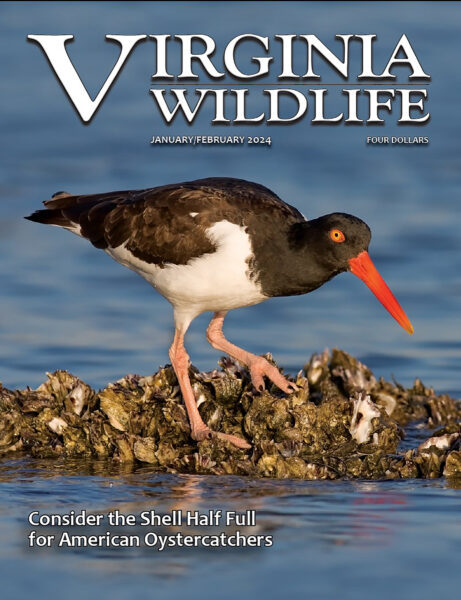

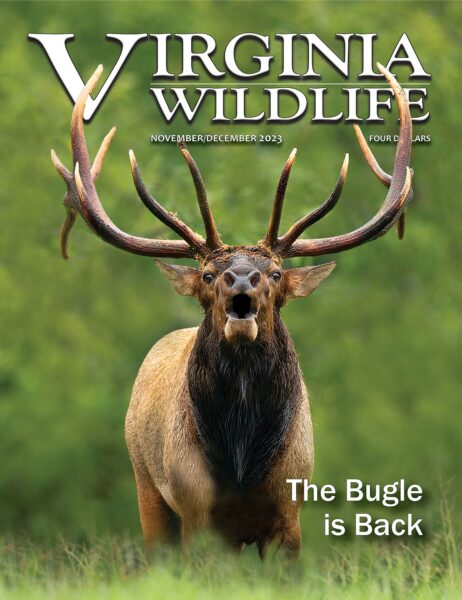

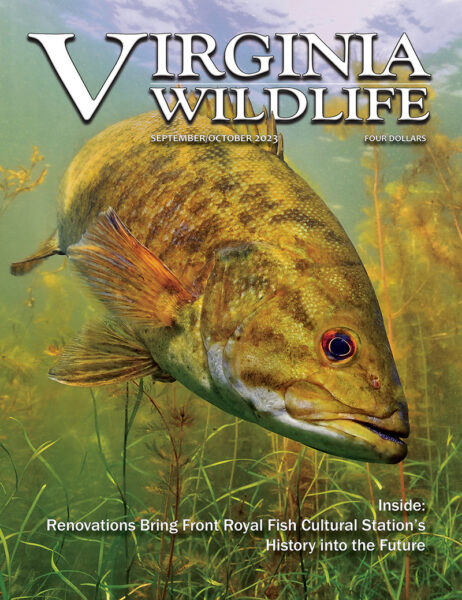

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe