Cropland

Row crops and small grain

To improve fields in row crops or small grain for quail, no practice is better than establishing field borders. As discussed in the techniques section for establishing borders, these can be provided with a minimum or even no acreage (cutback borders) taken from production. Also, the placement of borders can be where crop yields are poorest along woodland edges, or woody fence rows and drainages. These areas often produce low yields at a net loss to the farmer. Borders also provide readily available protective cover, required if quail are to glean harvested fields. Crop field borders can be attractive to quail for nesting or brooding as well. Pesticide application should be reduced or eliminated from the first 50 feet of the field edge.

Most row crops, with the exception of cotton and tobacco, can provide suitable conditions for brooding. Those planted no-till and having some weeds are particularly attractive. Of various seeding techniques considered in a North Carolina study, the greatest nesting and brood use occurred in late-season soybeans or double-cropped soybeans.

Installing sod waterways and filter strips is another management opportunity that can increase the quail’s use of crop fields. The North Carolina report concludes that grain farm management should incorporate both borders and filter strips to the greatest extent possible. These should be planted in a quail-friendly bunch grass/legume mixture for nesting or brood cover.

Crop stubble should be left on the field for as long as possible following harvest. Fall plowing should be avoided. Fields left unplowed over winter will be less prone to erosion and provide quail with cover and food. Quail will routinely appear for a meal of spilled corn, soybeans or sorghum for as long as these remain available. Turning hogs or cattle into stubble fields will reduce the amount of grain available to quail. Even more damaging, is the destruction of cover that occurs when cattle feed on the vegetation, especially honeysuckle, growing along field edges.

Leaving a few rows of crops unharvested next to good cover is a good quail management practice.

Hay fields

As with grain fields, any of the various techniques described for “Field Borders” can be applied to hay fields. Hay fields containing bunch grasses and forbs, particularly legumes, are often well suited for nesting. Simply leaving an unmowed edge at least 30 feet wide can provide the border needed for this activity. This can be of particular value to birds that have had nests destroyed when the balance of the field has been mowed, giving them a ready opportunity to renest. Unmowed edges can be left permanently idle, or to keep from losing them to woody growth, hay half of the edge alternately each year. Rock or tree outcroppings within hay fields can be left with an unmowed fringe.

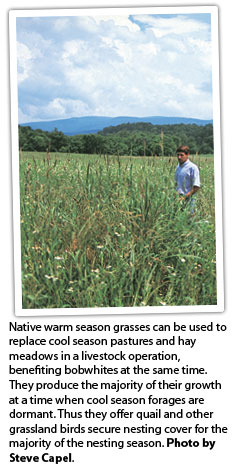

Conversion of tall fescue to NWSG will enhance nesting conditions and will produce a larger quantity of high quality hay. An advantage of native warm season grass is that haying occurs more than a month later than cool season hay, offering a chance for first nests to be successful before cutting commences.

Pastureland

Pastureland can also be managed in a fashion that will help quail. However, the type of forage growing and the extent to which it is grazed will profoundly effect its usage. Unimproved pasture (a rarity these days), moderately grazed, can be attractive to bobwhites for many activities, including nesting. With improved pastures, the most satisfactory are those growing a mix of warm- or cool-season bunch grasses and legumes. The latter, preferably clover or annual lespedeza. If these fields are not too heavily grazed, they will be used by quail for feeding and roosting. For any nesting to occur in improved pasture, fencing must be used to create safe havens. Intensely or overgrazed pasture, regardless of its plant species, has virtually no value to quail.

Like hay fields, the conversion of at least some pasture from fescue to native warm season grasses can benefit both the livestock grower and quail. Having pastures of both cool- and warm-season grasses gives the opportunity to establish a rotational grazing system where each type of grass can be utilized to their greatest benefit. Additionally, properly managed, warm-season grass will not be grazed as closely as fescue or other cool-season grasses, but will remain in a 12-inch stubble throughout the fall and winter. In particular, this will result in excellent roosting cover.