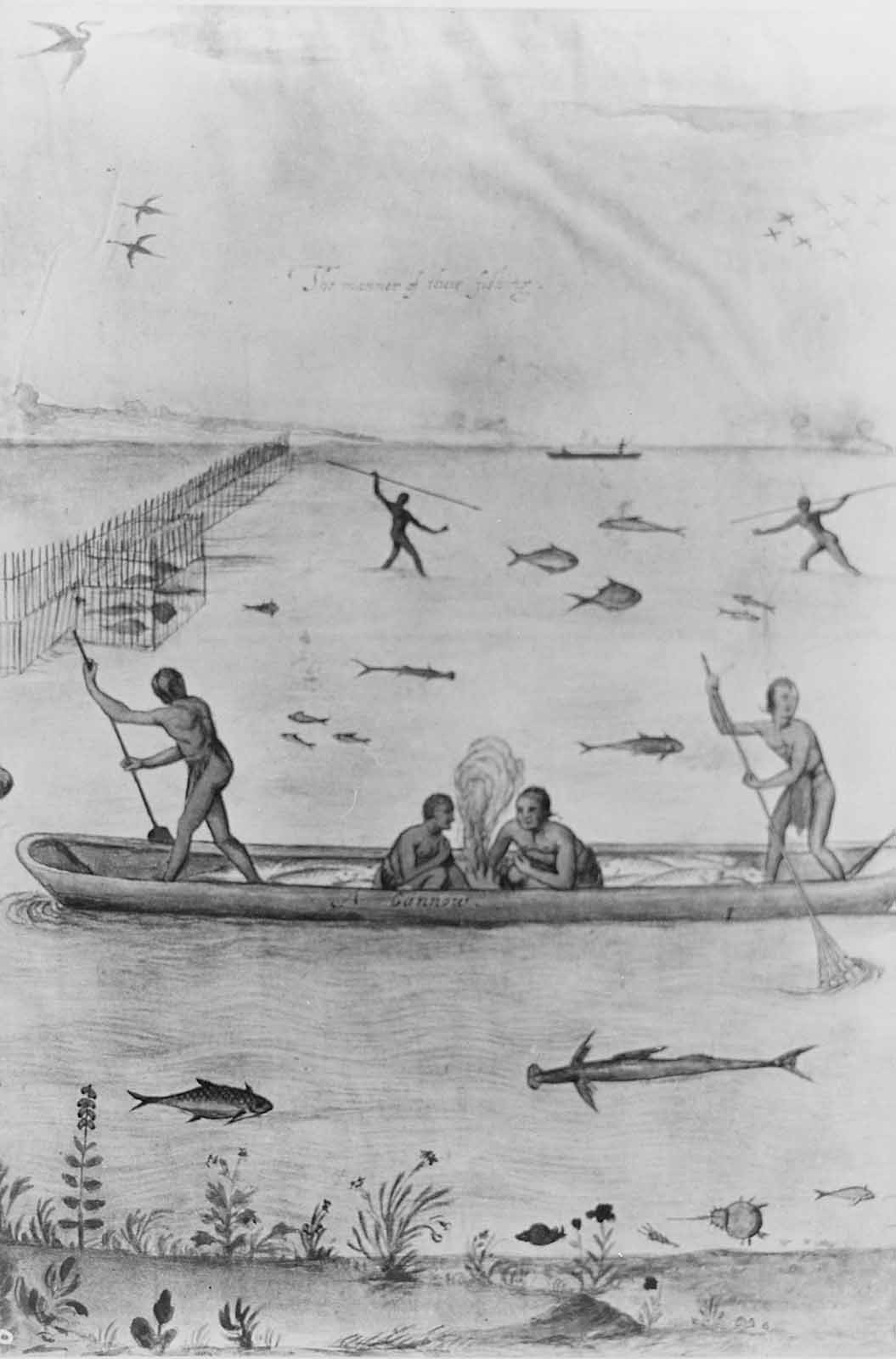

They’ve been called “America’s Founding Fish” because, in the past, the American shad was one of the Atlantic Coast’s most abundant and economically important fish. Shad were an important food source for Indigenous Peoples, early colonists, and generations of Virginians. George Washington took advantage of the bountiful Potomac River shad fishery by commercially fishing for shad, which provided both food and income for the Mount Vernon estate. Legend has it that an early shad run in the Schuylkill River (Pennsylvania) in 1778, during the Revolutionary War, fed Washington’s troops that were starving at Valley Forge, which in turn enabled them to fight on and help the United States earn victory. Though there’s little factual proof of that story, it’s a reflection of just how central shad have been to the culture and history of the country, and of Virginia.