What Is HD?

Hemorrhagic disease, or “HD”, is an important infectious disease of white-tailed deer in Virginia and the Southeastern United States, and outbreaks occur nearly every year.

What Causes HD?

HD is caused by two closely related viruses, epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus (EHDV) and bluetongue virus (BTV). There are 3 subtypes of EHDV and 5 subtypes of BTV commonly found in North America, with many additional subtypes found on other continents. Because disease features produced by these viruses are indistinguishable, the general term hemorrhagic disease is often used when the specific virus is unknown.

How Is HD Spread?

HD is not spread by direct animal to animal contact. Instead, nearly all viral transmission is through tiny biting flies in the genus Culicoides. These flies are commonly known as biting midges but are also called local names such as sand gnats, sand flies, no-see-ums and punkies.

When Does HD Occur?

HD typically occurs from mid-August through October, and this seasonality is related to the abundance of the biting midges. The onset of freezing weather, which stops the midges, brings a sudden end to HD outbreaks. How the viruses persist through the winter when midges are not active is not entirely clear.

What Are The Signs Of HD?

Outward signs in live deer depend partly on the virulence (potency) of the virus, duration of infection, and levels of immunity from prior exposure. Many affected deer appear normal or show only mild signs of illness. When illness occurs, the signs change as the disease progresses. Initially animals may be depressed, feverish, have a swollen head, neck, tongue, or eyelids, or have difficulty breathing. With highly virulent strains of the virus, deer may die within 1 to 3 days. More often, deer survive longer and may become lame, lose their appetite, or reduce their activity.

When Should You Suspect HD?

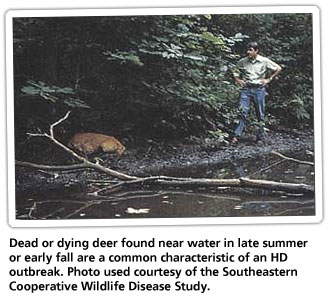

HD should be suspected in instances of unexplained deer mortality during late summer or early fall. Because the deer have a high fever during the first few days of the disease, dead or dying deer are often found near water (e.g., lying on or near the banks of ditches, creeks, lakes, rivers, etc.) lying on the cool moist soil.

What Should I Do If I Find What I Think Is A Dead Or Dying HD Deer?

Do not attempt to contact, disturb, kill, or remove the animal. Please report the approximate location of the animal(s) to the Department by contacting the Virginia Wildlife Conflict Helpline at (855)-571-9003. The Department maintains annual records of HD mortality reports documenting the location and approximate number of animals involved. Please be advised that unless there are extenuating circumstances, the HD report will not result in an onsite visit by Department staff.

How Many Deer Will Be Lost?

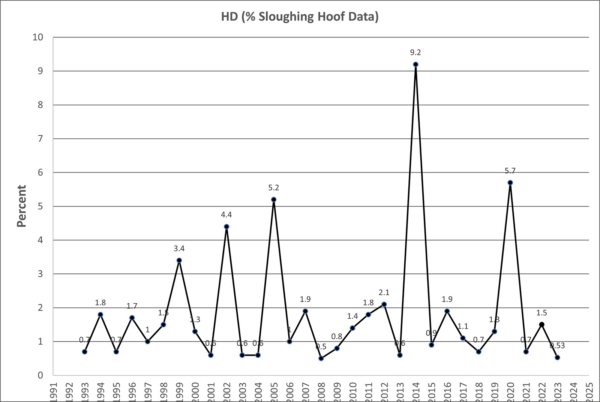

HD occurs annually in Virginia but its severity and distribution are highly variable (see the graph below). Past occurrences have ranged from a few scattered mild cases to widespread outbreaks in 1999, 2002, 2005, and especially 2014. In localized areas where HD is occurring, losses during the outbreak usually are well below 25 percent of the population, but, in a few instances, have been 50 percent or more. To date, there has never been a deer population eradicated by HD. Research conducted by the Department indicates that that there are three potential environmental predictors of HD activity in eastern Virginia; mild winters, hot summers, and a June drought. It is thought that higher winter temperatures increase over-winter midge survival, that higher summer temperatures increase midge populations and midge activity, and that a lack of precipitation in June may create favorable breeding sites for midges (mud flats) and diminish food and water sources for deer, concentrating deer on the landscape and increasing their physiological stress.

What Is The “Hoof Disease” That I Hear Deer Hunters Talk About Related To HD?

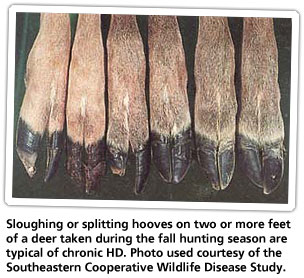

As noted above, many deer survive HD infections. In these surviving deer, the fever at the onset of the disease often causes growth interruptions in the hooves and later peeling or sloughing of the hoof walls (see photo). If a deer has sloughing/splitting hooves on two or more feet during Virginia’s general firearms deer season, it is likely that it had HD a couple of months earlier.

Was The HD Outbreak Caused By Overpopulation?

High-density deer herds may have higher mortality rates; however, the relationship of deer density to severity of HD is not clear-cut. The number of deer that are immune, the virulence of the virus, the number of livestock nearby, or the abundance of midge vectors may influence the outcome of infection within a deer population regardless of deer density. However, dense deer herds would be expected to support virus spread better than sparse herds.

High-density deer herds may have higher mortality rates; however, the relationship of deer density to severity of HD is not clear-cut. The number of deer that are immune, the virulence of the virus, the number of livestock nearby, or the abundance of midge vectors may influence the outcome of infection within a deer population regardless of deer density. However, dense deer herds would be expected to support virus spread better than sparse herds.

Are Livestock Affected?

In contrast to the significance of EHD and BT viruses to white-tailed deer, the importance of these agents to domestic livestock is more difficult to assess. Most BTV infections in cattle are clinically silent; however, a small percentage of animals can develop lameness, sore mouths, and reproductive problems. Cattle can be short-term BTV carriers. EHD viruses have occasionally been isolated from sick cattle, however most infections show only mild or no clinical symptoms. Serum surveys have shown that cattle often have antibodies to this virus, indicating frequent exposure. For domestic sheep the situation is more straightforward. Sheep are generally unaffected by EHDV, but bluetongue can be a serious disease similar to that in deer.

Will Livestock Become Infected From Deer?

Past observations have revealed that simultaneous infections sometimes occur in deer, cattle, and sheep. Discovery of illness in deer indicates that infected biting midges are present in the vicinity, and, thus, both deer and livestock are at risk of infection. Once virus activity begins, both livestock and deer potentially serve to fuel an outbreak; however, the spread of disease from deer to livestock, or vice versa, has not been proven. Furthermore, long-term carrier status for EHD or BT viruses has not been reported in deer.

Will HD Recur?

Yes. In Virginia, HD activity has exhibited relatively distinct geographic patterns. HD is common and occurs at some level annually in both the Tidewater and the Piedmont physiographic regions, but it is more common in the Tidewater than in the Piedmont. In the Piedmont, Southside and the central Piedmont tend to show more consistent HD activity than the northern Piedmont and the far southwestern Piedmont. HD has been documented west of the Blue Ridge in Virginia, but it is not as common.

Yes. In Virginia, HD activity has exhibited relatively distinct geographic patterns. HD is common and occurs at some level annually in both the Tidewater and the Piedmont physiographic regions, but it is more common in the Tidewater than in the Piedmont. In the Piedmont, Southside and the central Piedmont tend to show more consistent HD activity than the northern Piedmont and the far southwestern Piedmont. HD has been documented west of the Blue Ridge in Virginia, but it is not as common.

Can People Become Infected with HD?

Humans cannot become infected with either EHD or BT viruses and are not at risk by handling infected deer, eating venison from infected deer, or being bitten by infected biting midges. However, deer that develop bacterial infections or abscesses secondary to HD may not be suitable for consumption.

What Can Be Done To Prevent HD?

At present there is little that can be done to prevent or control HD. Risks will be minimized in deer herds that are maintained at moderate to low densities relative to the carrying capacity of the habitat. This same concept holds true for most other diseases and parasites of white-tailed deer. The best and only practical means of regulating deer populations is through recreational deer hunting, including the harvest of antlerless deer as necessary. Although die-offs of deer due to HD often cause alarm, past experiences have shown that mortality will not totally decimate local deer populations and the outbreak will be curtailed by the onset of cold weather.

Acknowledgement

Much of this text was taken from the Hemorrhagic Disease of White-tailed Deer brochure produced by the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 and is used with their permission. It has been adapted in places to “fit” a Virginia perspective. This brochure can be downloaded from the UGA website.