An adult wood turtle. Photo by J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

A hatchling wood turtle. Photo by J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR.

An adult wood turtle. Photo by J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

Fact File

Scientific Name: Glyptemys insculpta

Classification: Reptile, Order Testudines, Family Emydidae

Relatives: Bog Turtle

Conservation Status:

- State Threatened in Virginia

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need-Tier 1a on the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan

- Listed as Threatened under the Species at Risk Act in Canada

- Listed as an Appendix II species by CITES

Size: up to 9 inches in length

Life Span: 40 – 80 years in the wild and up to 58 years in captivity

Identifying Characteristics

This semiaquatic turtle has a broad, somewhat flat upper shell, called a carapace. The carapace is comprised of pyramid-shaped plates, called scutes, which give the wood turtle a sculptured appearance. The carapace is brownish gray overall with scutes in younger individuals showing fan-shaped black and yellow markings.

Adult wood turtle. Photo by John Kleopfer/ VDWR.

The scutes near the tail flare out and have serrated edges. The bottom part of the shell, the plastron, is yellow with each scute featuring a large, black blotch in its rear outside corner. The skin on a wood turtle’s head and back is dark brown to black, but the throat and underside range from vibrant red to orange to yellow. They have a flat snout and their upper jaw is somewhat notched.

Wood turtle plastrons. The male (left) has a concave plastron and the female’s (right) is flat. Photo by John Kleopfer/ VDWR

There are a couple of notable differences between males and females. Males are slightly larger than the females and have concave plastrons. Males also have larger, thicker tails, as well as larger scales and nails on the front legs. Hatchlings are gray-brown, lacking the vibrant coloration of the adults. Their carapace is circular in shape. Tails of hatchlings are almost equal to the length of the body.

Wood turtle hatchlings. Photo by John Kleopfer/ VDWR.

Known as “bottom walkers,” wood turtles are often seen crawling along the bottom of streams foraging for crayfish and other invertebrates.

An adult wood turtle foraging through its underwater habitat. Photo by John Kleopfer/ VDWR

Similar Species:

Wood turtles are occasionally confused with Eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina), which have a hinged plastron (belly) and a more domed carapace (shell) that’s lacks the pyramid shaped scutes. Although box turtles will occasionally enter bodies of water, they will never be found swimming below the surface or crawling along the bottom.

Habitat

The typical habitat for these semiaquatic turtles is a forested stream with clear, moderately flowing water; a gravel bottom; and deep pools with sufficient amounts of leaf litter for overwintering. The ideal surrounding forested flood plain would be one with a mix of mature and young forest as well as some interspersed open, wet meadows.

Diet

Wood turtles eat a wide variety of plants, fungi, and invertebrates. Common food items include flowers, fruits and berries, mushrooms, slugs, and earthworms.

Distribution:

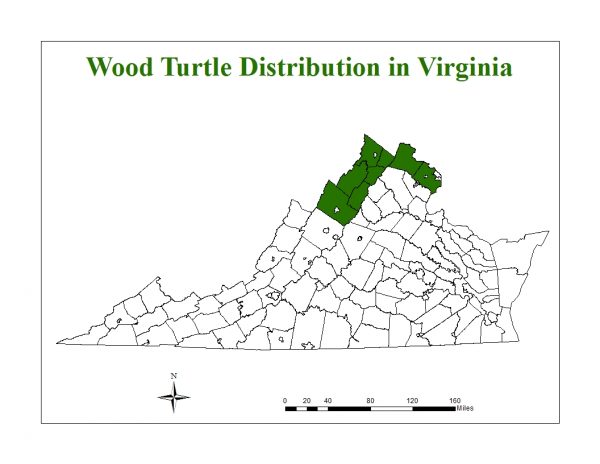

Wood turtles range from northern Virginia through the Northeast and into Canada, including adjacent provinces and Nova Scotia. They also range westward across the Great Lakes region of Quebec, Ontario, Michigan, and Wisconsin and into Minnesota and Iowa. In Virginia, they are only found in the northern part of the state in portions of the Shenandoah and Potomac River watersheds.

Where Do They Go in the Winter?

Wood turtles brumate, which is a type of hibernation that reptiles and amphibians undergo in cold weather. In the fall (October – November), they move into cold, slow moving streams and rivers to begin their brumation period and do not emerge until late winter-early spring (March-April). Beginning in December, they spend the winter resting in undercuts along stream banks with overhanging roots and logs, in beaver lodges, muskrat burrows, or at the bottom of deep pools buried in leaf litter packs, just atop or just below the substrate. However, it is not unusual to see them active underwater on warm winter days and early spring days.

An example of a wood turtle’s habitat. In the fall and winter, they brumate in slow moving streams and rivers. Photo by J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

Worm Stomping

Wood turtles perform a unique feeding behavior, in which they “stomp” the ground with their chest to attract worms to the surface. It’s believed that the worms react this way because the vibrations of the turtle’s movements mimics that of rain or the sound of a mole coming their way, a known predator of earthworms.

Role in the Web of Life

In 2021, the DWR’s Restore the Wild initiative featured this winning artwork depicting a wood turtle strolling through its underwater habitat. Art by Miranda McCleaf

Because of their preference for clean, cold-water streams, wood turtles serve as excellent indicators of stream health and water quality as well as the overall health of a stream’s surrounding landscape.

Eggs, hatchling, and juvenile wood turtles are potential prey for raccoons, river otters, coyotes, foxes, opossums, ravens, herons, crows, and skunks. Adults have few natural predators other than river otters, but these instances are rare.

Where to See in Virginia

In Virginia, wood turtles are only found in the northernmost part of the state. However, we do not recommend actively searching for them as they are a state protected species and therefore illegal to possess.

Conservation

The Road to Recovery

The wood turtle’s Virginia range once included portions of the northern Piedmont, but the species’ population has declined dramatically in this region, largely due to urbanization and resulting habitat degradation and loss. Additional threats include being hit by vehicles while crossing roads, predation of nests by raccoons in suburban areas, and illegal collection.

DWR and SCBI biologists recording wood turtle data during a fall survey. Photo Credit: J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

To address these threats, the Northeast Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (NEPARC) formed the Northeast Wood Turtle Working Group (NEWTWG) in 2011. Their goal was to ensure that healthy, viable populations of wood turtles are conserved across the landscape. To achieve this goal, NEWTWG identified regionally significant conservation priority sites for the wood turtle, called the Conservation Area Network. In Virginia, 16 sites were identified as high priority Focal Core Areas for the wood turtle and 4 sites were identified as second priority Management Opportunity Sites.

What the DWR Has Done/Is Doing

The Virginia DWR and the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) have been working together for more than a decade to develop the science needed to conserve the wood turtle in the Commonwealth. As a result of this work and our joint participation in the NEWTWG, we created a Virginia Wood Turtle Conservation Plan, completed in 2020, based on the larger regional plan described above. The goal of this Conservation Plan is to preserve viable wood turtle populations within the Commonwealth. The DWR and SCBI have already begun several actions to address the plan’s objectives.

DWR biologist with wood turtle captured during a fall survey. Photo credit: J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

Management Planning

We created management units for both the Northeastern range of the wood turtle and for the Commonwealth. In Virginia, we identified five large management units, at the watershed basin scale, to allow for cohesive management across the 20 smaller Focal Core Areas and Management Opportunity Sites outlined in the regional plan.

Science and Research

We are coordinating with partners in the Midwest to update the protocol we have utilized for visual encounter surveys since 2014, thus standardizing the methods across a larger portion of the species’ range. In order to analyze and respond to changing land use, we have also developed an environmental DNA (eDNA) protocol for rapid assessment of the presence / absence of wood turtles. eDNA is a pioneering science in which trace amounts of DNA shed by living organisms is collected and analyzed to identify the presence of a target species.

Smithsonian-Mason School of Conservation students assisting with surveys and recording wood turtle data. Photo credit: J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

In collaboration with the Smithsonian’s Center for Conservation Genomics, we validated the identification of wood turtle populations in several habitat types within the Commonwealth. Since collection of eDNA through stream water filtration is sensitive to environmental conditions, we are also testing and developing a more robust eDNA collection protocol for use across a broader spectrum of streams and geographies.

In addition to continued monitoring of wood turtles throughout the Commonwealth, certain key populations have been the focus of intensive research that is striving to clarify several aspects of the wood turtle’s life history, crucial to informing its long-term conservation. Eventually, the data from this research will result in an analysis on a key population of wood turtles in the George Washington National Forest (GWNF) that will be generalizable to a substantial portion of the remaining wood turtle populations in Virginia.

Law Enforcement

The Collaborative to Combat the Illegal Trade in Turtles (CCITT), SCBI, and the Virginia DWR’s Conservation Police Officers have been discussing surveillance methods to address the illegal pet trade, including the potential implementation of a PIT tag system that would allow officers to pinpoint the source population from which a confiscated animal was taken. This would help us prosecute offenders and potentially relocate poached turtles.

Outreach and Education

We have been developing the Best Management Practices for both public and private landowners and exploring options for managing wood turtle on private lands, such as through the Working Lands for Wildlife program by the Natural Resource Conservation Service. Additionally, we deliver talks and presentations promoting wood turtle awareness and best management practices to students, landowners, and the public.

The majority of wood turtle habitat in Virginia is found on private land, so education and outreach for landowners is critical to their conservation. Photo credit: J.D. Kleopfer/ DWR

Habitat Restoration

The DWR has been providing consultation on how to manage for wood turtles during stream habitat restoration efforts in Northern Virginia. We have provided this assistance to the U.S. Forest Service for two upcoming restoration projects in the GWNF. We also provided consultation to a private landowner who completed a successful stream restoration on his property that has benefitted wood turtles and trout. (Location information is intentionally withheld.) The landowner reports that, “The wood turtles are multiplying and breeding all up and down the restored stream. They like the instream habitat and rocky stream banks that we created for them.”

Hatchling wood turtles emerging from a protected nest site. Nest protectors keep out raccoons and other predators. Photo credit: J.D. Kleopfer

How You Can Help

- Purchase a Restore the Wild Membership to support the DWR’s habitat restoration work.

The membership also serves as your pass to visit over 40 state Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) and Lakes throughout the Commonwealth.

The membership also serves as your pass to visit over 40 state Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) and Lakes throughout the Commonwealth. - Donate to the DWR’s Non-game Fund to support research and conservation of Virginia’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need, like the wood turtle, as well as conservation education and wildlife viewing recreation.

- Landowners and land managers in Northern Virginia can help by limiting potentially hazardous activities within 300m of known wood turtle streams and nest sites. For a detailed list of best practices, refer to “A Guide to Habitat Management for Wood Turtles.”

- Do NOT disclose locations of wood turtles given that illegal collection and trading are one of their major threats. Citizen science projects and use of iNaturalist should avoid posting any locality information for this species.

Sources

Akre, Meck, VanDoren and Kleopfer. 2020. Virginia Wood Turtle Conservation Plan. Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. Henrico, VA. 38 pp.

Akre, T.S., L.D. Parker, E. Ruther, J.E. Maldonado, L. Lemmon, and N.R. McInerney. 2019. Concurrent visual encounter sampling validates eDNA selectivity and sensitivity for the endangered wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta). PloS ONE 14(4), p.e0215586.

Jones, M.T., H.P. Roberts, and L.L. Willey. 2018. Conservation Plan for the Wood Turtle in the Northeastern United States. Report to the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Species Profile Authors: Jessica Ruthenberg, DWR; John Kleopfer, DWR; Tom Akre, SCBI; J. Hunter VanDoren, SCBI; and Jessica Meck, SCBI

Last updated: February 5, 2024

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources Species Profile Database serves as a repository of information for Virginia’s fish and wildlife species. The database is managed and curated by the Wildlife Information and Environmental Services (WIES) program. Species profile data, distribution information, and photography is generated by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, State and Federal agencies, Collection Permittees, and other trusted partners. This product is not suitable for legal, engineering, or surveying use. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources does not accept responsibility for any missing data, inaccuracies, or other errors which may exist. In accordance with the terms of service for this product, you agree to this disclaimer.