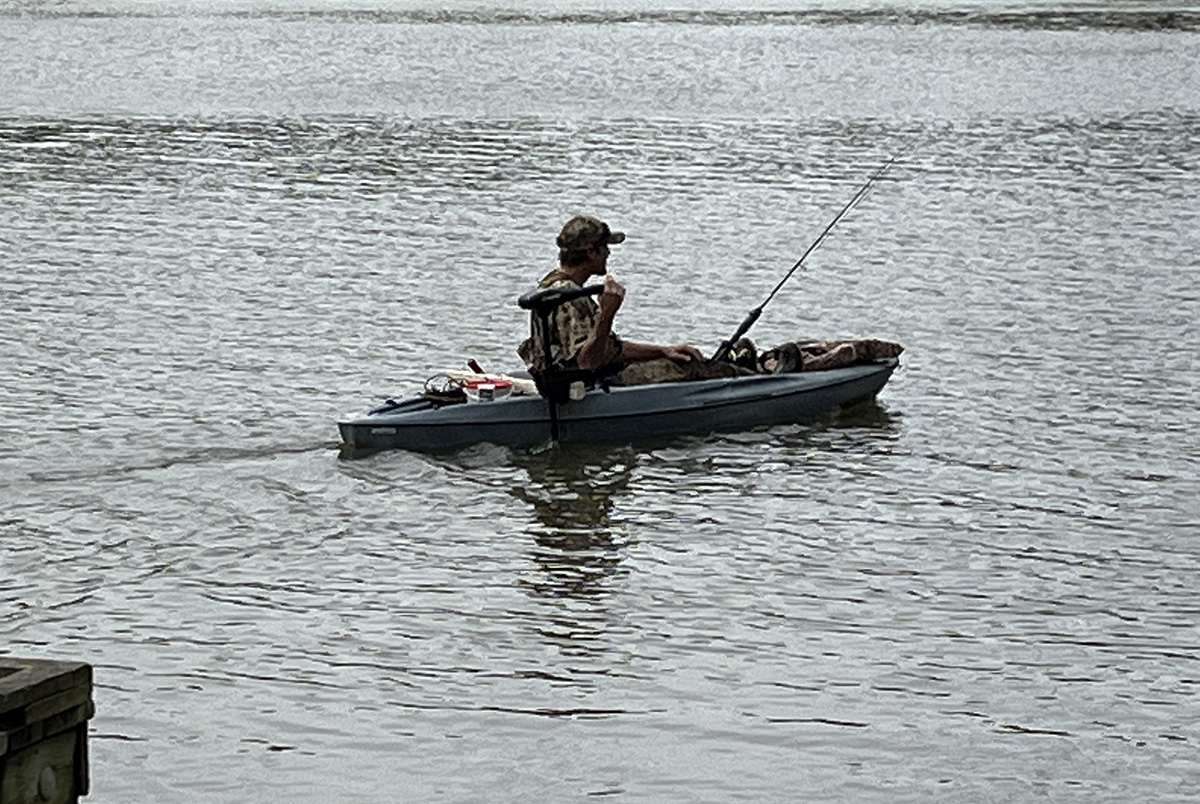

The view out on Morris Creek from the DWR boating access site.

By John Page Williams

Photos by John Page Williams

No matter the season, nor what boat you choose, there is something worth seeing and doing on Charles City County’s Morris Creek and the Chickahominy River, to which it flows. Fortunately, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) provides us with an excellent two-lane, textured concrete boat ramp, and adjacent pier for launching canoes, kayaks, and outboard skiffs up to 20′ or so.

The Morris Creek landing is part of DWR’s Chickahominy Wildlife Management Area, 5,217 acres of mixed hardwood and pine stands; cultivated, mowed and “old field” openings; and tidal fresh wetlands. Morris Creek forms its southern boundary, and the Chickahominy River its eastern margin. The uplands create excellent habitat for deer, turkeys, squirrels, rabbits, doves, and songbirds. Waterside bald cypress trees and tall, dead snags serve bald eagles and ospreys (in season) for nest sites, lookouts, and fish scouting. The creek’s marshes and several interior beaver ponds attract waterfowl. The WMA is on DWR’s Bird and Wildlife Trail. See here for a list of seasonal sightings from Virginia eBird.

For explorers, birders, and anglers in paddlecraft, there’s enough to see and do in the creek to stay busy all day. The landing lies roughly in the creek’s midpoint, with a couple of miles of winding waterway both up and downstream. Although privately owned, the land opposite the WMA is commercial timberland, so the area feels completely secluded. A canoe or a kayak makes a great vehicle for birding and fishing, with the usual cautions about dressing for the weather (including an appropriate life jacket!) and letting someone know both where you’re going and when you expect to return.

Three more cautions: first, a narrow creek with wooded banks naturally funnels wind; pay attention to the forecast and match the paddling challenge to your skill level. Second, Morris Creek goes through a roughly two-foot tide change twice a day (you can check NOAA’s prediction for the main river just outside the creek’s mouth). Third, the current in a deep tidal creek like this can be powerful, up to a couple of knots. It pays to set your itinerary around the wind and current on any day you’re out there.

Navigating Morris Creek in an outboard skiff may be physically easier, with the engine doing most of the work, but the winding channel presents its own challenges. The basic rule is that the channel will follow the outsides of the curves, so the deeper water will tend to be on the wooded sides, with shallow mud on the marshy sides. And that deeper side can be seriously deep.

It’s fascinating to watch how the currents in a creek like Morris—and in a big river like the Chickahominy—shape their channels. As they accelerate around the outside, they scour deep holes like this one, while the water on the inside of the curve slows down, allowing sediment to settle and form marshes. These are classic meander patterns. On our recent visit, we saw several turns in the creek that were 25′ deep, with one in the main river above the creek’s mouth of 70′.

Those inside turns, though, and coves where streams carry rainwater out of the WMA’s woods, catch the rich sediment the creek’s water carries and put it to excellent use. Here, on Morris Creek’s mudbanks, grow some of the Chesapeake’s richest tidal fresh marshes. In late summer and fall, the dominant plant is wild rice, growing five to eight feet tall and producing literally tons of nutritious grains for birds like sora rails migrating through and waterfowl that will winter here. Other grain- and seed-bearing plants that contribute food for those birds include rice cutgrass, smartweeds, tearthumbs, beggarticks (whose golden blossoms complement the rice in fall), and Walter’s millet.

The cypress trees are unusual among conifers in that they are deciduous: their needles turn rich hues of russet heather in the fall, adding to the colors of the creek’s hardwoods. Like the hardwoods, they will be bare all winter, but they will bring a beautiful promise of delicate green as spring brings life back to Morris Creek’s uplands and marshes.

The creek’s meandering pattern creates fish habitat on both sides, helping produce the fishery for which the Chickahominy is well known. The deep holes form warm, stable refuges for fish like blue catfish and white perch in cold weather and, paradoxically, cool water in summer’s heat. Bankside trees that fall into the creek form current breaks, behind which predators like largemouth bass can ambush prey being swept past. Deeper parts of trees attract black crappie, which feed on shiner minnows trying to hide in the limbs. Look especially for cypress trees and their knees, which can hold fish of multiple species.

Look for yellow perch (“ring perch”) in the creek’s headwaters in early spring. The shallow flats on the insides of the turns attract foraging bass as water warms. Morris Creek’s marshes are large enough that creeks have formed in several to drain rainwater from them. These can be hotspots for both white and yellow perch, and bass will seek out current eddies at their mouths to ambush baitfish as falling tide flushes them outward.

In any tidal creek or river, tide and current are major factors in the ways fish use their available habitat. Here’s an excellent DWR article on how to fish the tides on the Chickahominy. (Look here for more of DWR’s Fishing Reports, Forecasts, and Notes from the Field articles.)

All of this information applies, of course, to the Chickahominy River itself. It’s a much larger, more powerful version of Morris Creek. By all means, if you can, venture out into it. Be careful as you navigate the S-turn at the creek’s mouth, keeping firmly to the outsides of the curves, as the water is extremely shallow on the insides and in the middle.

Outside, you’ll find yourself looking down past the Route 5 bridge to the Chickahominy’s mouth, where it meets the James. Half-a-mile across lies the mouth of Gordon’s Creek, another beautiful tidal fresh tributary, with a dozen more creeks to explore in the 20 miles of river leading up to Walker’s Dam. If Morris Creek is large and rich enough to keep a paddler busy for a full day, doing justice to the Chickahominy in a skiff would take a lifetime.

John Page Williams is a noted writer, angler, educator, naturalist, and conservationist. In more than 40 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Virginia native John Page championed the Bay’s causes and educated countless people about its history and biology.