By Garrett Clevinger for Whitetail Times

White-tailed deer have long been regarded as one of the most resilient game species in North America. Like in many other states, deer in Virginia were nearly hunted to extirpation by the start of the 20th century. Only through collaborative efforts between conservation agencies and hunting groups have whitetail populations been able to drastically rebound to what they are today.

From the mid-1920s to the early 1950s, deer restocking efforts were in full swing across the state, with deer being trapped and relocated throughout the commonwealth from 11 other states. However, in certain pockets west of the Blue Ridge Mountains, remnant herds of Virginia’s native deer herd could still be found in fair numbers, especially throughout Bath, Highland, and Alleghany Counties. As such, deer hunting has remained a cherished pastime within the region for decades, even drawing many out-of-state hunters year after year.

Nevertheless, deer harvests—on both private and public lands—declined throughout these same areas since the mid-1990s, until recently when they appear to have stabilized at lower densities. Therefore, the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) partnered with researchers at Virginia Tech in 2018 to gain a better understanding of deer population dynamics within these mountainous systems by initiating the Virginia Appalachian Deer Study (VADS).

To recap, researchers at Virginia Tech conducted field work on three unique study sites in Bath County: Gathright Wildlife Management Area (owned and managed by DWR), Hidden Valley Recreation Area (owned and managed by the U.S. Forest Service), and Warm Springs Mountain Nature Preserve (owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy). The sites were selected in efforts to provide a diverse gradient of landcover types and habitat management applications to incorporate into analyses. Field methods for the study required capturing deer (both adults and fawns) and outfitting them with tracking collars to determine key population metrics (e.g.., survival rates, variations in mortality from different causes, and population growth indices) within the region.

Earlier articles on the study:

The Virginia Appalachian Deer Study: How Fawns are Faring West of the Blue Ridge Mountains

In total, VADS staff was able to successfully collar a total of 38 adult and 57 fawns throughout Bath County. At the time of the update, results from predator genetics analysis were still forthcoming. The purpose of this work would provide the VADS with genetic data from different predator species obtained from things like saliva on carcass remains and/or scat found at individual fawn mortality sites.

Virginia Tech Ph.D. student Garrett Clevinger observes for fetus presence using a portable ultrasound machine while field technicians Braiden Quinlan (left) and Abby Stone (right) assist in the work-up process. Once pregnancy is confirmed, a vaginal implant transmitter (VIT) will be implanted into the doe to aid crews in fawn capture during the summer.

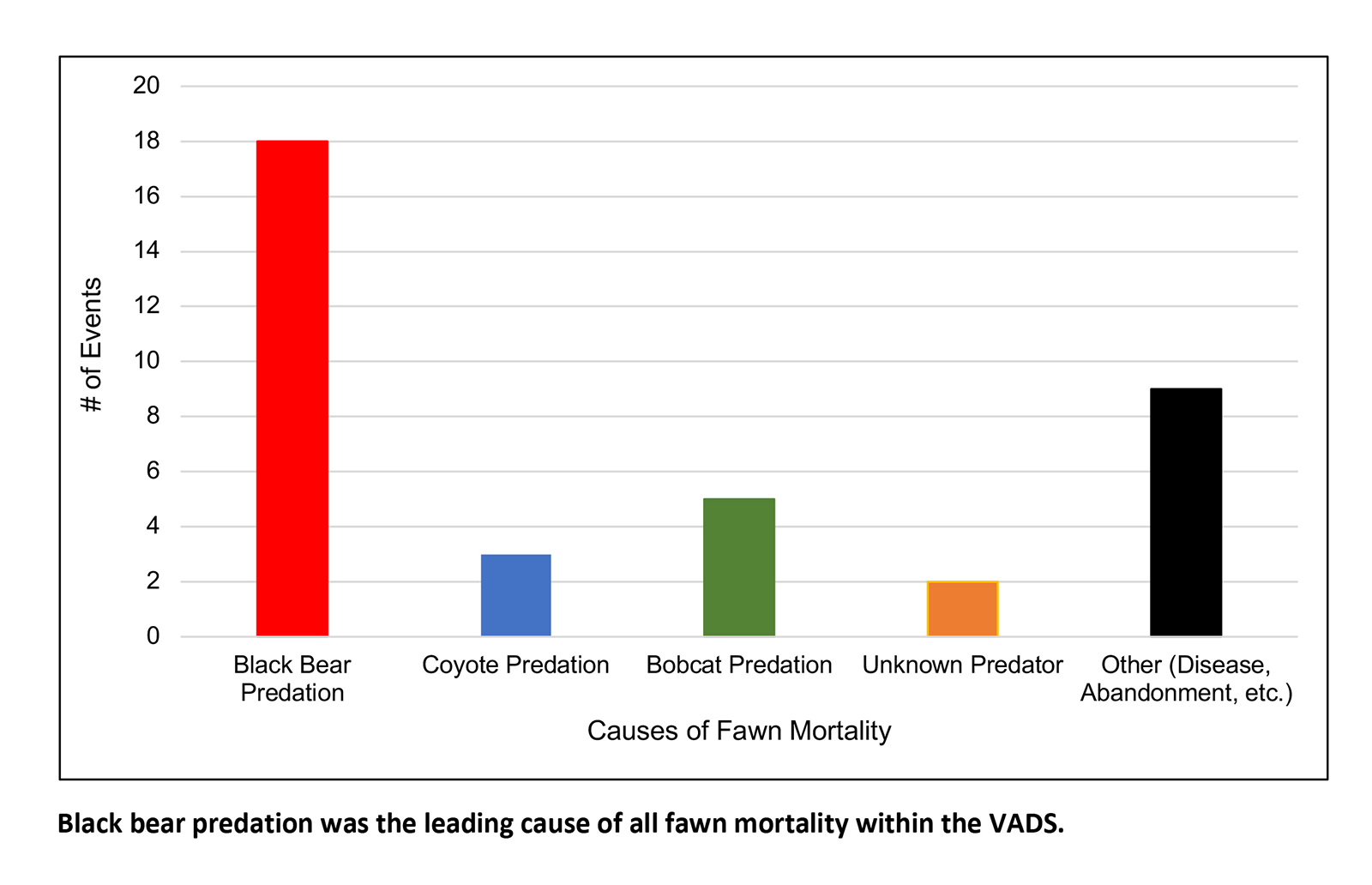

In 2021, VADS personnel sought assistance from wildlife biologists at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University-Kingsville to assist with the predator genetics analysis. When the analysis had concluded, the crew was able to accurately identify predator DNA on swabs from 14 fawn mortality events, providing additional evidence for eight bear predation events, three bobcat predation events, and three coyote predation events.

Additionally, of those predation events that were genetically confirmed to species, VADS field diagnostics correctly identified the predator responsible 100 percent of the time. Moreover, there were six events in which only the collar was found, with no carcass remains to determine cause of death. In all but one of these instances, the genetics analysis was able to confirm both predation and the species responsible in the cause of death. This allowed the VADS crew to reincorporate these fawns into the survival dataset.

Combining data from both initial field investigations and predator genetics analysis, the VADS crew observed a final 12-week fawn survival rate of 31 percent (0.310; 0.210-0.457). Similar to the previous update, black bears accounted for most fawn mortalities (n =18; 48 percent of all mortality), followed by bobcats (n = 5) and coyotes (n = 3). Again, the VADS sought to determine if specific habitat characteristics were influencing fawn survival rate. As such, the team measured habitat associations from capture locations of fawns. Elevation was the most important predictor of fawn survival, with fawn mortality risk increasing as elevation increased.

Utilizing data from both fawns and adults, the VADS predicted whether the deer herd in Bath County was increasing or decreasing, and at what rate. An additional goal of the VADS was to determine how changes in doe harvest and fawn survival would impact the population over time in Bath County. Previous research has shown that adult female survival is typically the most important parameter influencing deer population growth, which is why wildlife managers often prioritize limiting doe harvest in areas where deer populations appear to be declining.

As such, reducing season lengths and bag limits on antlerless deer within these regions of concern can often negate other negative impacts, such as low fawn recruitment. However, in situations where fawn recruitment is too low, increasing adult female survival may have minimal positive impacts to the population—especially in areas that already have restrictive regulations in place.

To conduct these analyses, the VADS needed to have some estimate of deer population size within the study area. Luckily, the crew was able to reference some recent literature where other researchers at Virginia Tech used distance sampling to determine a range of deer density within Bath County between 12.03-41.60 deer/mi2 (see Montague et al. 2017). From there, the VADS incorporated known data from different age classes of collared deer into the model to estimate current growth trends for deer herds in Bath County. This included estimated rates of survival from collared fawns, as well as both survival and fecundity (e.g., number of fawns per doe) from collared adult does into the model.

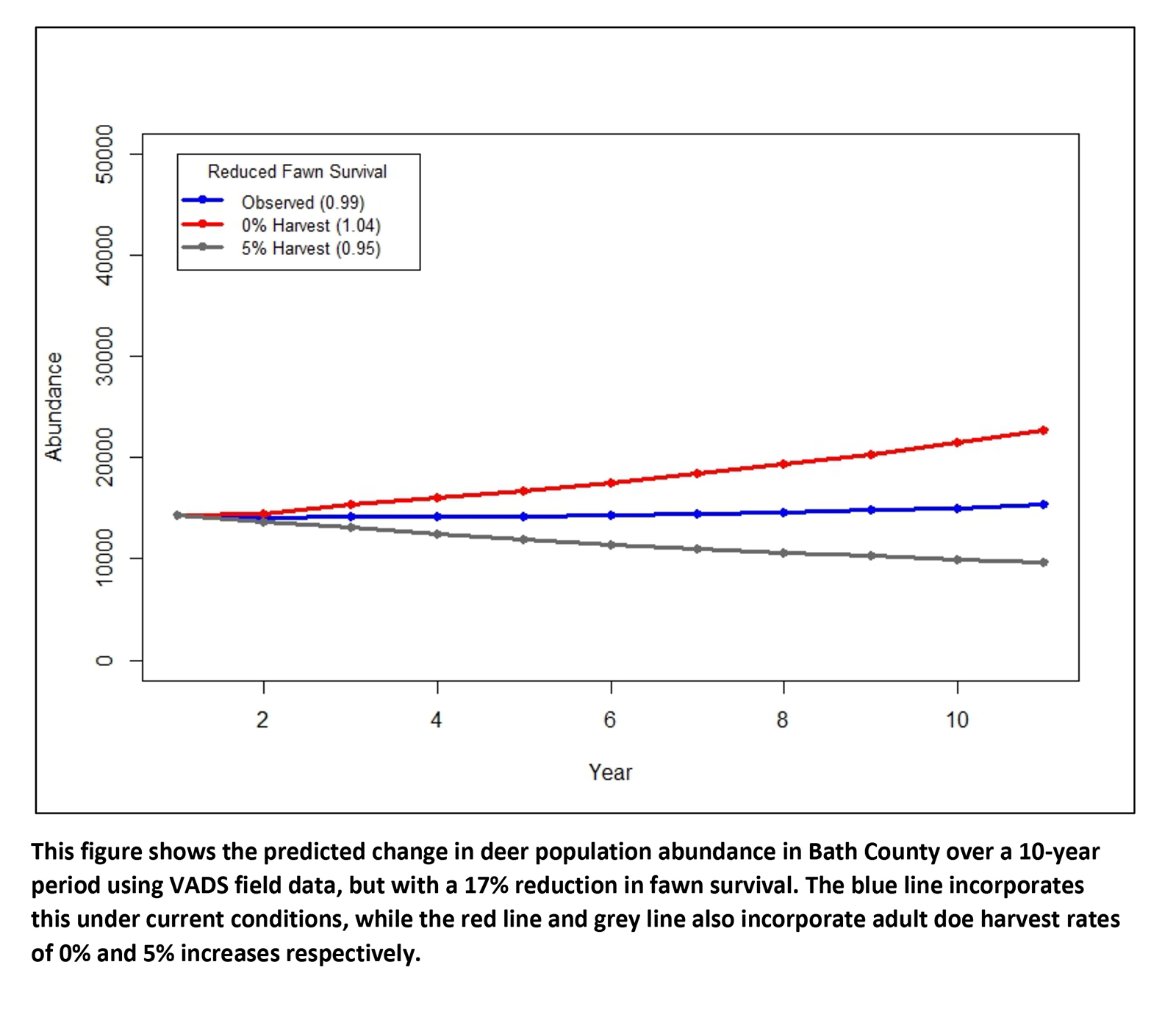

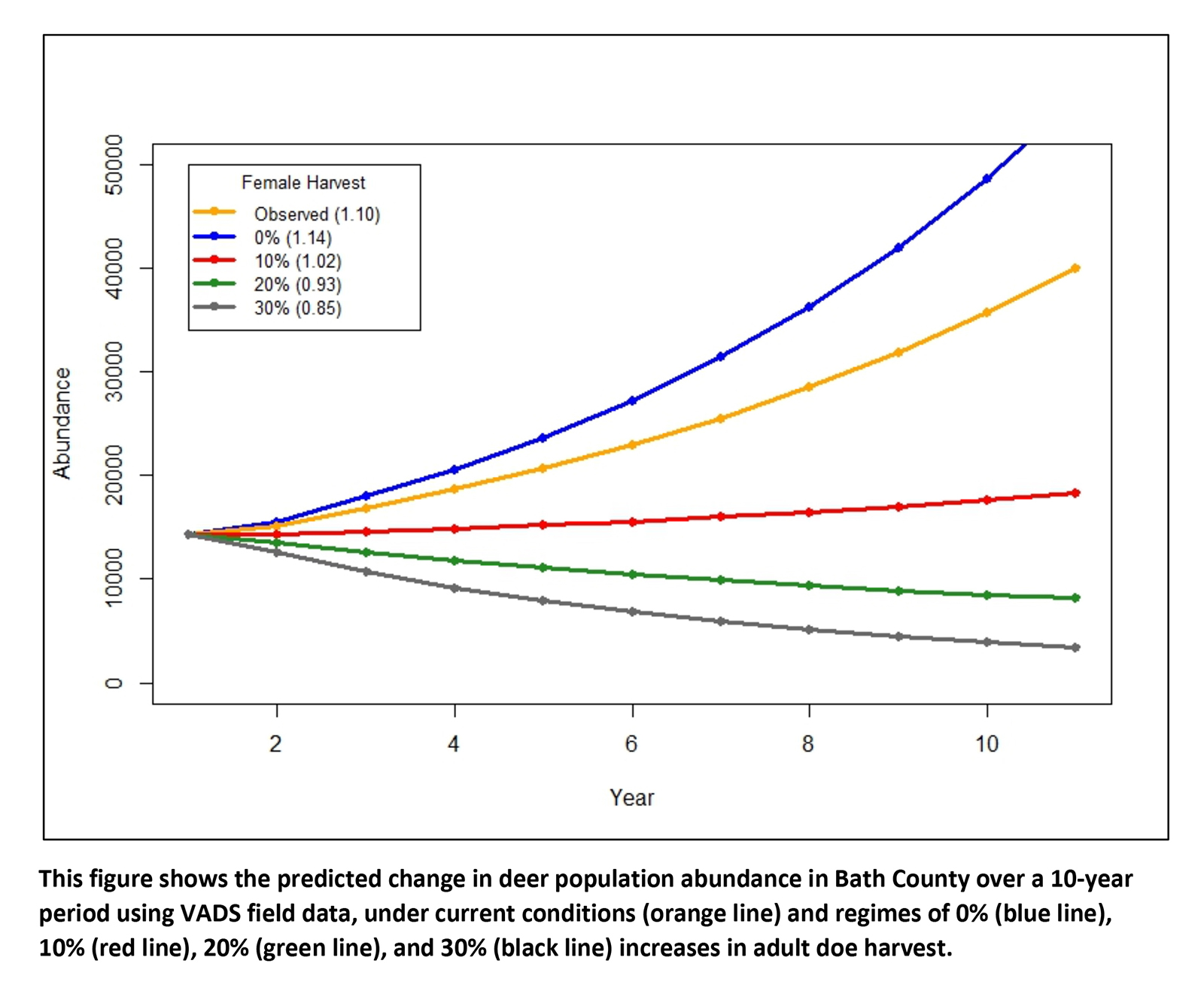

Next, VADS researchers compared observed population trends to hypothetical “what if” scenarios that projected how the deer herd in Bath County would fare under different constraints, such as various levels of adult female harvest (0 percent, 10 percent increase, 20 percent increase, and 30 percent increase), reduced fawn survival (17 percent decrease; obtained from previous literature), and combinations thereof.

Surprisingly, the VADS analysis revealed that, under current conditions, the deer population in Bath County was increasing by 10 percent each year. Moreover, the model also predicted that the herd would still increase by 2 percent each year even if it sustained an additional 10 percent increase in adult female harvest. The model predicted that the population would start to decline by 7 percent each year if it experienced a 20 percent increase in adult female harvest.

When determining the influence of reduced fawn survival, the model predicted a stable population. When looking at the cumulative influence of both a reduced fawn survival rate and a 5 percent increase in adult female harvest, the population began to decline. However, if adult female harvest was reduced to 0 percent, then the population began to increase again—even with the 17 percent reduction in fawn survival. As expected, under all scenarios (both observed and hypothetical) adult female survival was the most important variable influencing population growth in the Bath County deer herd.

Drawing accurate conclusions about deer populations by harvest trends alone can be a difficult endeavor for deer managers and continues to be an issue of concern for many state wildlife agencies across the county. One primary reason for this is associated with declining rates of hunter recruitment and hunter effort, especially in mountainous regions across the Appalachians. In these systems, previous research has shown that most hunters are unlikely to access areas that at are further from roads and more difficult to traverse and, as a result, many of the more rugged areas that stay devoid of hunters within these mountainous systems now act as refuges for deer (especially on large tracts of public land). As such, it could be that reduced harvest rates within these areas are more a product of fewer deer hunters that are willing and/or able to hunt in areas where the deer typically are.

Ultimately, even with intensive research efforts, there are still limitations that may prevent researchers from telling the whole story. As such, it’s important to note that because the VADS occurred over a short period, it is possible that the deer population in Bath County had already declined previously and that the years analyzed (i.e., 2019-2021) were not representative of population trends occurring over the last few decades.

Even if the VADS model projections are optimistic, it certainly does not appear that the deer herds in Bath County are declining; this is actually backed up by recent harvest data from the area.

What the VADS simulations can infer is that increasing fawn survival rates should be a secondary concern compared to limiting adult female harvest if the management goal is to increase populations. Therefore, given the goals of increasing the deer population in Bath County, findings from the VADS suggests that maintaining low adult female harvest and enacting active habitat management actions (e.g., timber management, prescribed fire) that would enhance nutritional condition of deer (i.e., benefits all population vital rates) could potentially increase deer population growth.

Garrett Clevinger graduated from Virginia Tech, where he received his doctoral degrees, and now works for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency as the state’s deer program coordinator.

©Virginia Deer Hunters Association. For attribution information and reprint rights, contact Denny Quaiff, Executive Director, VDHA.