Fact File

Scientific Name: Ursus americanus americanus

Classification: Mammal

Conservation Status:

- There are approximately 900,000 black bears in North America.

Life Span: Bears may live up to 30 years in the wild. The oldest documented wild female bear in Virginia was 30 years of age when it was killed and the oldest male was 25.

Identifying Characteristics

Of the three bear species (black, brown, and polar bears) in North America, only the black bear lives in Virginia. Shy and secretive, the sighting of a bear is a rare treat for most Virginians. However, bears are found throughout most of the Commonwealth, and encounters between bears and people are increasing. A basic understanding of bear biology and implementing a few preventative measures will go a long way to helping make all encounters with bears positive.

Adult black bears are approximately 4 to 7 feet from nose to tail, and two to three feet high at the withers. Males are larger than females. Black bears have small eyes, rounded ears, a long snout, large non retractable claws, a large body, a short tail, and shaggy hair. In Virginia most black bears are true black in color unlike black bears found in more western states that can be shades of red, brown or blond. The muzzle is brown and there is an occasional white chest blaze.

Depending on the time of year, adult female black bears commonly weigh between 90 to 250 pounds. Males commonly weigh between 130 to 500 pounds. The largest known wild black bear was from North Carolina and weighed 880 pounds. The heaviest known female weighed 520 pounds from northeastern Minnesota.

Habitat

Incredibly adaptable, black bears occupy a greater range of habitats than any bear in the world. Bear home ranges must include food, water, cover, denning sites and diverse habitat types. Although bears are thought to be a mature forest species, they often use a variety of habitat types.

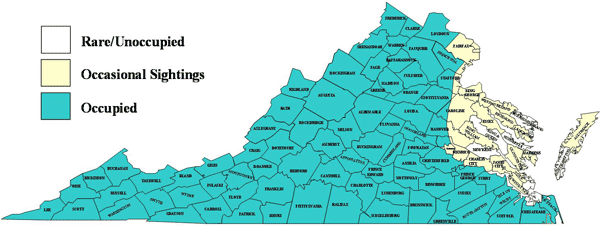

Black bears can be found all along the Appalachian Mountains, in the Piedmont area, as well as sporadically along the coast. They prefer habitat that provides cover, such as a densely wooded mature oak forests or swampy area in the coastal plain, and easily accessible food resources.

Distribution:

The American black bear is found only in North America. Black bears historically ranged over most of the forested regions of North America, and significant portions of northern Mexico. There are approximately 900,000 black bears in North America. Black bears reside in every province in Canada except for Prince Edward Isle, and in at least 40 of the 50 states in the US. In the eastern United States, black bear range is continuous throughout New England but becomes increasingly fragmented from the mid-Atlantic down through the Southeast.

Solitary or Social?

Black bears are generally solitary, except females caring for cubs. Adult bears may be seen together during the summer breeding period and occasionally yearling siblings will remain together for a period of time. On rare occasions, yearling bears may even stay with the adult female until the next denning season. Bears may also gather at places with abundant food sources.

Daily Activity Time

Black bears are typically crepuscular (active at dusk and dawn), but can be active any time of day, particularly if there are food resources nearby.

Movements

Female black bears have smaller home ranges (1 to 50 square miles) than males (10 to 290 square miles). A male’s home range may overlap several female home ranges. Bears may move further in times of less food like early spring or during poor mast crop years. Dispersing yearlings, especially males, looking for new home ranges may also travel a great distance. Adult bears have been known to travel over 95 miles in a year, and will occasionally mark trees with their claws, especially during the breeding season.

Breeding and Cubs

Five-day old black bear cub. Photo by Mike Vaughan, VT.

Female black bears mature as early as three years old. Breeding occurs from mid-June to mid-July, but in the eastern deciduous forest, mating season can extend into August. Female black bears usually breed every other year and cubs are born from early January to mid-February. The cubs are born very nearly hairless and weigh 6-12 ounces (less than a pound!). Anywhere from 1-4 cubs are born at a time and are raised by their mother for about 1½ years. They are able to leave the den with the adult female in the spring and they disperse during their second spring. First-year cub mortality rates are about 20%, primarily due to predation (foxes, coyotes, dogs, bobcats, other bears), abandonment by their mother, or displacement. Adult bears do not have natural predators except humans.

When the mother is ready to breed again, she will send her yearlings to fend for themselves during the summer months when food is usually abundant. Always hungry, these yearling bears, particularly the males, will seek easy sources of food. The ability to access human related food sources can spell trouble for these bears.

Denning

Bears may feed up to 20 hours per day, accumulating fat (energy) prior to winter denning. An adult male can gain over 100 pounds in a few weeks when acorn production is heavy. Depending on weather and food conditions, black bears enter their winter dens between October and January. In Virginia, most bears in mountainous areas den in large, hollow trees. Other den types include fallen trees, rock cavities, and brush piles in timber cut areas, open ground nests, and man-made structures (e.g., culvert pipe, firewood lean-to, etc.). Dens are usually lined with a bed of leaf litter and they have been found up to 96 feet above the ground ( they are good climbers.)

Bears may feed up to 20 hours per day, accumulating fat (energy) prior to winter denning. An adult male can gain over 100 pounds in a few weeks when acorn production is heavy. Depending on weather and food conditions, black bears enter their winter dens between October and January. In Virginia, most bears in mountainous areas den in large, hollow trees. Other den types include fallen trees, rock cavities, and brush piles in timber cut areas, open ground nests, and man-made structures (e.g., culvert pipe, firewood lean-to, etc.). Dens are usually lined with a bed of leaf litter and they have been found up to 96 feet above the ground ( they are good climbers.)

Bears will not eat, drink, urinate or defecate while denning. Bears are easily aroused and may be active during warm winter days. On occasion they may venture from their dens, walk about, and return to denning. They emerge from their dens from mid-March to early May.

Mange and Black Bears

Mange in Virginia Bears

Although black bears are susceptible to several types of mange, sarcoptic mange is of most concern in Virginia. From 2014 to 2017, sporadic reports of mange were primarily focused in the northwestern mountain counties of Frederick and Shenandoah. Since 2018, reports have increased in frequency and geographic spread, and mange has been confirmed in 24 counties (as of July 2024). DWR asks anyone who sees a bear showing signs of mange as described below to take photos, note your exact location (take GPS coordinates, if possible), and submit this information to the VA Wildlife Conflict Helpline at vawildlifeconflict@usda.gov or (1-855-571-9003). These reports are vital for tracking the spread and frequency of mange on the landscape, while also providing critical information necessary for making regulation and management changes. As discussed further below, public reports are also used extensively during research efforts.

What is Mange?

Sarcoptic mange is a highly contagious skin disease caused by microscopic mites affecting many wild and domestic mammals. DWR is actively involved in multiple studies to better understand the disease dynamics and characterize the mite(s) responsible for mange in Virginia’s bear population. In the scientific literature, at least four different mite species have been previously reported in bears; however, results to date indicate that most mange in Virginia bears is caused by a common skin-burrowing mite, Sarcoptes scabiei. This species causes sarcoptic mange in a wide variety of hosts, including scabies in humans, and has several host-adapted variants (e.g. canis, hominis, suis, etc.). To date studies indicate that Sarcoptes mites from Virginia bears are a canid variant genetically similar to the mites affecting other states in the region (WV, MD, and PA.)

How Does Mange Spread Between Bears?

Currently, there are many unknowns related to the occurrence and spread of mange in bears. Research efforts are underway to understand these processes. Mites are easily transferred to a new host when an unaffected animal comes into direct physical contact with an infested individual. In addition, mites that fall off an infested host can persist in the environment under ideal conditions for up to 2 weeks and may infect a new animal that enters a contaminated site.

Because bears are relatively solitary, the biggest risk for environmental transmission likely occurs under conditions where they congregate, either naturally (e.g. dens, mating) or unnaturally (e.g. garbage cans, bait piles, bird feeders, and other food resources).

What Are Signs a Bear Has Mange?

The clinical signs of mange are a result of damage to the host’s skin by the burrowing mite, the immune reaction of the host, the physical skin trauma that occurs through scratching, and the secondary bacterial infections that subsequently develop. Clinical signs include:

The clinical signs of mange are a result of damage to the host’s skin by the burrowing mite, the immune reaction of the host, the physical skin trauma that occurs through scratching, and the secondary bacterial infections that subsequently develop. Clinical signs include:

- Intense itching

- Mild to severe hair loss

- Thickened, dry skin covered by scabs or tan crusts, often around the face and ears

- Altered behavior (e.g. lethargy) and/or poor body condition in severe cases

- The extent of these clinical signs is variable, ranging from small hairless areas on the ears, face, or body in mild to moderate cases, to extensive hair loss and skin lesions covering nearly the entire body in severe cases. Severely affected bears are often thin or emaciated, lethargic, and sometimes found wandering apparently unaware of their surroundings.

How Does Mange Affect Bear Populations?

Although mange can be a cause of mortality in black bears, there has been no clear evidence from other states with longer histories with mange that the disease limits populations over the long-term. However, localized population declines have been observed recently in some mange-affected areas of Virginia, particularly in counties with historical liberal harvest seasons. A multitude of factors including increased harvest seasons to meet population objectives, successive years of poor hard mast production (primarily red and white oaks), and increased winter temperatures, in conjunction with mange, have likely contributed to declining trends in several bear management zones. Additional research is currently being conducted that will provide information on survival, movements, transmission routes, and potential susceptibility of certain populations in Virginia. More information on the current research can be found below.

What is DWR Doing About Mange in Bears?

DWR takes the problem of mange and its potential implications on black bears seriously. An ongoing and critical step is continuing to work with the public to collect reports of mange-infested bears. The information gathered from these reports and submission of biological samples has helped DWR to tailor response protocols, provide better information to the public, make regulation changes, and focus research efforts.

Accurate data on mange-affected bears is helping us track spread and potential modes of transmission and create procedures to quickly confirm cases in new areas. This data is also being shared cooperatively with neighboring states and wildlife health professionals to collaboratively determine potential impacts on bear populations and develop long-term management strategies.

There are still many unknowns about mange in black bears. Bears are resilient animals and many survive infestations of mange. A study conducted in Pennsylvania recently showed 74% of bears with a mild to moderate case overcame the infestation without any intervention. DWR evaluates each mange report on a case-by-case basis to determine an appropriate response. For many bears that are still in acceptable body condition and behaving normally, DWR does not recommend humane dispatch or other interventions. Reports are monitored and bears are only humanely dispatched if they become severely affected (poor body condition, altered behavior, and/or unlikely to survive). Reports of mange in new areas outside of the 24 positive counties are responded to in accordance with established field protocols to quickly assess whether an animal is infested with mange or not.

Beginning in 2024, DWR partnered with the College of Natural Resources and Environment at Virginia Tech to begin an innovative mange research project spanning multiple years and areas of Virginia. Primary objectives of this project include determining population densities and abundance in both mange affected and non-mange affected bear populations using DNA collected from hair; understanding behavioral differences between mange affected and non-affected populations by monitoring movements, space use, and reproductive parameters; and creating an adaptive harvest regulation model. Samples collected during field research for this effort will also be used to assess multiple health parameters of black bears. In addition to the Virginia Tech project, DWR provides samples for a multi-state research effort, led by the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study at the University of Georgia, which is studying mite genetics, bear genetics, and other factors possibly contributing to mange infestations.

More information on the Virginia Tech research project will be shared through the project-specific website. Check back for updates on field work, photographs, and insights from the students!

For more information about how DWR is addressing mange in Virginia, please read the Black Bear Mange Management Plan.

Can Mange in Bears be Treated?

Although there are many effective treatment options for dogs and other domestic animals, few have been studied in bears and there are significant hurdles to effectively and ethically treating wild animals. DWR, in cooperation with The Wildlife Center of Virginia, treated black bears infested with sarcoptic mange with ivermectin or fluralaner during a two-year experimental trial beginning in 2017. While hair regrowth and resolution of skin abnormalities were observed in treated bears, upon release back to their home range, a number of these bears became re-infested with mange and exhibited even more severe clinical symptoms within one year of their release. In addition, ongoing research in other states has not demonstrated long-term effectiveness of treating bears with mange, and as stated above, did not significantly increase the percentage of individuals that recovered naturally.

There are also many potential consequences of treating bears, including tissue residues leading to human drug exposure through consumption, contributing to drug resistant parasites with improper dosages or treatment regimens, and concerns for non-target species or the environment. Additionally, routine preventative treatment of wild animals (e.g. monthly dosing as is often done for flea and tick prevention in pets) is simply not feasible at a landscape level. Therefore, DWR does not consider treatment as a viable option at this time.

What You Can Do to Prevent the Spread of Mange

- Minimize the congregation of bears (and other animals) by removing or securing potential attractants.

- Discontinue feeding birds or other wildlife. If a mange-infested bear has been reported or seen in the area, stop feeding pets outside and pick up any uneaten food and food/water bowls.

- Move outside garbage or compost containers into a bear resistant shed, garage, or other secured location or prevent access with electric fencing.

- To help DWR track the distribution of this disease, continue to report all suspected cases of mange to the Department through the VA Wildlife Conflict Helpline (vawildlifeconflict@usda.gov or toll free 1-855-571-9003). Photos or videos of the suspect animal are extremely helpful. Information submitted to the Wildlife Conflict Helpline helps DWR track the distribution of the disease and is not intended to provide an emergency response to a reported mange bear.

Visit the DWR Black Bear webpage for more information on living with black bears in Virginia as well as additional information on mange in black bears.

What if I Harvest a Mange-Infested Bear?

If a hunter harvests a bear with signs of mange during an open bear season (regardless of condition/degree of infestation), they must utilize their bear tag and report the bear at the time of harvest because this information remains a vital element of DWR’s bear management program. Hunters should carefully evaluate bears before harvest and refrain from harvesting bears that show any signs of mange. Instead, take photos and a GPS point of the location and provide this information to the wildlife conflict helpline (vawildlifeconflict@usda.gov or 1-855-571-9003).

Because humans can contract mange, handling of the bear carcass isn’t required, and the bear does not need to be removed from the place of harvest.

A photo of the bear (at the time of harvest) along with GPS coordinates or specific location should be collected.

IMPORTANT: The harvested bear should also be reported to bearmange@dwr.virginia.gov with the photo and confirmation number from reporting the harvest. DWR will evaluate the submission and contact the hunter regarding license status or to collect additional information on the harvested bear’s condition. If you do not have access to email you may call the VA Wildlife Conflict Helpline as soon as possible (1-855-571-9003), however there may be some delays when reporting by phone.

Best Management Practices for Possible Exposure to a Mange-Infested Bear

- Handling of a mange-infested bear should be minimized to avoid unnecessary exposure. Hunters should take precautions if handling and/or disposing of the pelt and carcass. These precautions include wearing disposable gloves, using a permethrin-based insect repellent on clothes/gear (as instructed by the label), bagging gloves and any other disposable equipment after use, and disposing of these items in a dumpster or similar location. Hands and arms should be washed thoroughly with soap. Contaminated clothing should be washed and machine-dried with heat or placed in a freezer overnight to kill any mites. If the carcass of a bear with signs of mange is removed from the harvest site, the hunter should try to dispose of the pelt by returning it to the site of harvest or double bagging and placing in the trash or landfill.

- Hunters should contact their veterinarian to discuss options for any hounds that may have come into contact with a mange-infested bear or an area occupied by a mange-infested bear (e.g., den, bedding site, etc.).

- Equipment (dog leashes, dog box, etc.) should be disinfected (e.g., 40% bleach solution or other disinfectant cleaner for equipment and clothing) if suspected of being in contact with a mange-infested bear or with a dog that has come into contact with a mange-infested bear.

- Contact your health care provider for more information related to a potential human exposure to mange.

More Information

Visit DWR’s Wildlife Disease page for more information or download the Black Bear Mange brochure.

Last updated: February 23, 2026

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources Species Profile Database serves as a repository of information for Virginia’s fish and wildlife species. The database is managed and curated by the Wildlife Information and Environmental Services (WIES) program. Species profile data, distribution information, and photography is generated by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, State and Federal agencies, Collection Permittees, and other trusted partners. This product is not suitable for legal, engineering, or surveying use. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources does not accept responsibility for any missing data, inaccuracies, or other errors which may exist. In accordance with the terms of service for this product, you agree to this disclaimer.