By Meagan Thomas/DWR

Welcome to the second post in our regular series about the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Seabird Colony! In case you missed our first post, ‘Enter the World of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel Seabird Breeding Colony’, you can read it here. As many of our followers know, South Island and Rip Raps Island (also referred to as Ft. Wool) are the two critical pieces of land related to this project. They are both small, artificial islands adjacent to the south opening of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel. In fact, the two aren’t even completely separated as they are connected via a thin strip of riprap about 300 feet long.

Despite this connection, they couldn’t be more different when it comes to seabird management. The DWR and partners have invested thousands of hours into making Rip Raps Island an idyllic safe haven for the birds during the nesting season; meanwhile, just mere feet away, an equal amount of time is being spent at South Island to deter the birds from establishing a summer home onsite. This month’s update contains all the details.

But before we get to that, some exciting news—our first arrivals for 2021 nesting have begun to appear onsite around Ft. Wool! A recent trip to the island documented several hundred royal terns and laughing gulls. There were no signs of our other species of interest (i.e. common terns, gull-billed terns, and black skimmers) just yet, but they are sure to be arriving any day now. In addition to the royal terns and laughing gulls, we are also happy to report that the snowy egrets have returned to the rookery on the east end of the island. Furthermore, three pairs of American oystercatchers, one of my personal favorite shorebird species, were observed during this trip. While American oystercatchers are not a part of the seabird colony displaced from South Island, they are still a Tier 2a Species of Greatest Conservation Need and a welcome sight to see around the island!

One of the oystercatcher pairs had an active nest that we were able to observe while on site. Their nests and eggs blend in with the surrounding habitat incredibly well and thus can be difficult to spot. Take a look at the image below and see if you can find the egg hidden amongst the riprap!

American oystercatcher egg from Rip Raps Island (left) and adult American oystercatchers (right). Photos by Meagan Thomas/DWR and Mike Weimer/USFWS

Every Dog has its Day on South Island…

The vast majority of colonial seabird species, including those found at the HRBT site, will return to the same location year after year to nest and raise their young. Once this site fidelity is established, it can be incredibly difficult to break this habit. When expansion-related construction began at the tunnel last year, South Island (the island the birds historically chose to nest on) was completely paved over and no longer safe for nesting. However, providing the birds with a safer and more attractive alternative on Rip Raps Island alone was unlikely to be enough to get them to completely give up on their old South Island stomping grounds. With this in mind, DWR biologists worked with the Virginia Department of Transportation and its contractor (Hampton Roads Connector Partnership) on the development of a Bird Management Plan to make South Island as unattractive as possible to the birds when they returned.

Flyaway Bett, Zoe and Hoop all decked out in their safety gear. Photo by Flyaway Geese.

One of the unique elements to this Bird Management Plan is the use of specially trained border collies and handlers to deter birds from the island. While this may sound a bit unorthodox, the use of trained dogs to chase off unwanted birds has become an increasingly popular technique used by private wildlife control companies. Border collies are an ideal breed of dog for the job because their movements while herding are incredibly similar to the head-down and tail-between-the-legs stalking movements of natural predators of ground nesting birds, e.g. wolves and coyotes. However, because border collies were bred for herding as opposed to hunting or retrieving, they have no natural instincts to actually contact or “mouth” the birds—instead they simply want to herd them. And while the border collies may love their jobs herding birds, the birds don’t appreciate the presence of a dog stalking them. After a few run-ins, the birds generally get the message and move on to other areas.

The dogs and handlers were first used at South Island in 2020. The plan then was to have two handlers and three dogs that would go out once an hour on rotating shifts to stalk any birds on site from sunrise to sunset. However, after just two weeks in, the technique proved to be so effective that it was upped to a rotating schedule of 12 handlers and 20 dogs. By the end of last year’s season they had a 100% success rate without a single nest on South Island.

Flyaway Bett hard at work on the HRBT North Island. Photo by Flyaway Geese.

Thanks to the company Flyaway Geese, the dogs are back this year. There are 10-12 dogs and three to four handlers on the island at any given time, doing hourly patrols 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, but teams are rotated weekly to prevent any dog or person from burning out. A recent conversation with Rebecca Gibson, the owner and founder of the company, indicated that 2021 is shaping up to be an even more challenging year due to the amount of on-site construction relative to what was happening on site in 2020. The dogs are spending more time patrolling the riprap around the island than they did last year, but don’t worry—they’re fully capable of navigating over the rocks and even have their own safety gear while on the job, including reflective vests, boots, life jackets, and goggles.

And while the dogs and handlers do their part to keep South Island bird-free, on the other side of the cove Ft. Wool is being set up to be as enticing a nesting site as possible to the birds.

Birds of a Feather Flock Together…

From top left to bottom right: common tern decoy, black skimmer decoy, royal tern decoy, gull-billed tern decoy. Photos by Meagan Thomas/DWR.

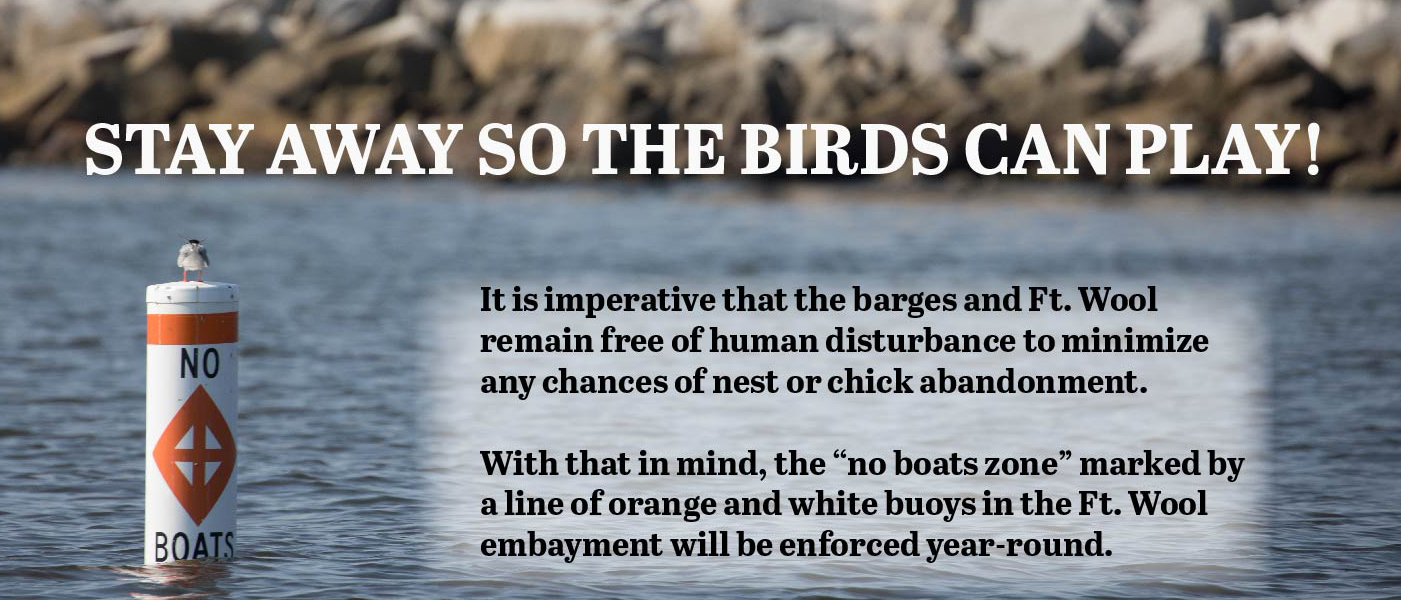

In addition to their preference to return to the same nesting grounds each year, seabirds also prefer to nest in large aggregations, or colonies, hence the name “colonial” seabirds. The presence of conspecifics, or members of the same species, plays a large role in attracting seabirds to new nesting grounds. Because these social cues are so important when convincing the birds to nest somewhere else, we deploy a variety of different decoys that mimic our species of interest out on the Ft. Wool parade grounds and the barges each year. The decoys are exceptionally realistic and produced by Mad River Decoys (owned by the National Audubon Society), which specializes in the creation of rare and endangered seabird decoys. This year, we have a suite of royal tern, common tern, gull-billed tern, and black skimmers decoys in place on the parade grounds and common tern, gull-billed tern, and black skimmer decoys on the barges.

Left: Kelsi Hunt of the Virginia Tech Shorebird Program helps set up one of the solar-powered sound systems at the Fort Wool site. Photo by David Norris/DWR. Right: A speaker that’s attached to the sound system will play seabird calls to attract birds to nest at the Fort Wool site. Photo by Kelsi Hunt/Virginia Tech.

And, because appearances can be deceiving, it’s also important that it not only looks, but also sounds like other birds are nesting at a potential new site. As you can likely imagine, colonies made up of thousands of birds are incredibly loud. With that in mind, our partners at the Virginia Tech Shorebird Program have installed a series of weatherproof speakers that broadcast the calls and chattering of our species of interest 24/7 on both the parade grounds and the barges. Check out the audio recordings below to hear the exact clips we use out on the island and barges. And if you want to make it a truly realistic experience, try playing all four at once and see if you can discern the individual species!

So there you have it, folks! Two entirely different islands and two entirely different management strategies that are working hand in hand to achieve a common goal, all in the name of seabird conservation. Be on the lookout for next month’s update (now available here!), and if you are not currently subscribed to our once a month Notes from the Field newsletter where this series is published, you can do so by clicking here. Just remember to check the box for wildlife updates when signing up. See you next month!

Black Skimmer Colony Calls

Common Tern and Black Skimmer Colony Calls

Gull-billed Tern Colony Calls

Royal Tern Feeding Group Calls

Seabird decoys used to attract the colony to Ft. Wool and the barges. Photo by Meagan Thomas/DWR.