By Molly Kirk/DWR

Restore the Wild funding will help complete habitat projects on three of Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) during the 2022-2023 funding season—two in the coastal plain and one in the mountains.

At the Hog Island WMA, Restore the Wild funding will enable the Wildlife Area Manager to establish approximately 2 acres of native warm-season grass and wildflower meadow and scrub/shrub habitat and treat an additional 8 acres and 5,500 linear feet of invasive vegetation surrounding the recently installed 24/7 livestreaming Marsh Cam located along the southeastern bank of the Hog Island WMA.

Some of the areas of Hog Island WMA identified for Restore the Wild-funded habitat work.

The Hog Island project seeks to enhance shoreline vegetation along one of the most biologically significant wetland complexes owned and managed by DWR. Thousands of migratory and resident birds use the WMA annually, and it supports heathy populations of upland wildlife including deer, turkey, and numerous small mammals, meaning the establishment and maintenance of high quality habitat has the potential to benefit a large number and wide range of wildlife.

This project will benefit a host of Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) listed in Virginia’s Wildlife Action Plan, particularly those that prefer the presence and maintenance of early successional habitats, shrub thicket, and wildflower meadows. Many neotropical migratory birds, gamebirds, song birds, and native insects have experienced strong population declines in recent decades. These declines are largely attributed to the loss of early successional and grassland habitats.

Species expected to benefit from the work include the eastern towhee, field sparrows, American woodcock, brown thrasher, eastern kingbird, eastern meadowlarks, grey catbirds, northern bobwhite, northern harrier, yellow-breasted chat, and a host of pollinating insects including monarch butterflies and frosted elfin.

At Gathright WMA in the mountains of Bath County, the Wildlife Area Manager is looking to re-establish early successional areas important for cerulean warblers. Early successional fields and pollinator species will be restored by controlling invasive autumn love and setting back woody succession. The Restore the Wild funds will help completed 10 acres of the restoration, with an additional 7 acres restored by in-house staff and non-profit coordination. A local non-profit, the Appalachian Habitat Association, will join the effort with volunteer time and equipment.

The project location at Gathright WMA.

These fields would support field openings nearby on Bolar Mountain, which is actively managed with fire and spot herbicide. Additionally, it will support golden-winged warbler projects approximately 2 miles from the WMA property. This will also help with fragmentation very commonly found in the mountain region and allow more open spaces for neo-tropic birds.

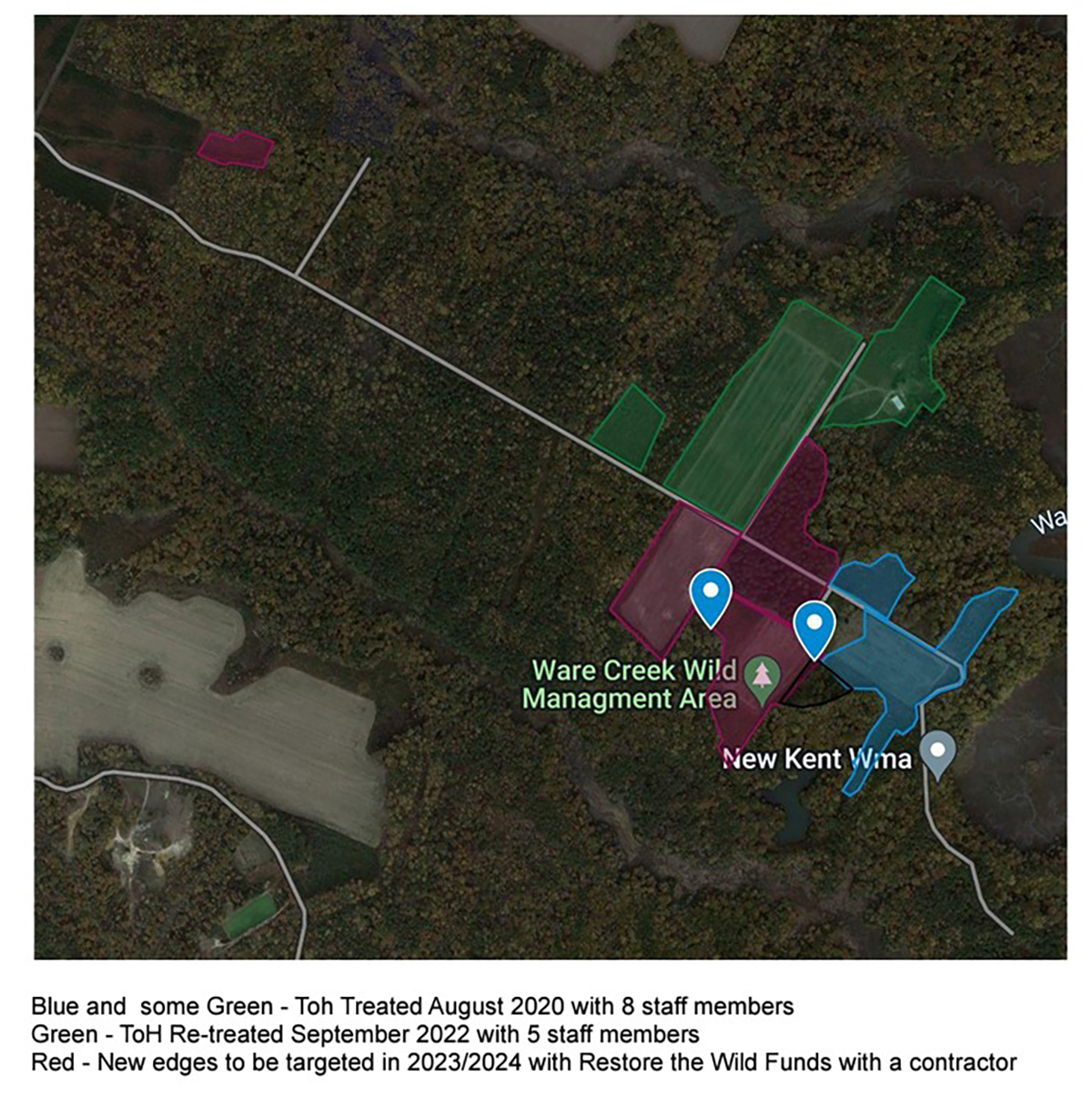

Back on the coastal plan, the Wildlife Area Manager at Ware Creek WMA will focus on restoring field/forest edge, early successional habitat by removing invasive vegetation, creating more than 20 acres of habitat beneficial for northern bobwhite quail, woodcock, yellow breasted chat, and monarch butterflies in addition to the game species of white-tailed deer and wild turkey.

Areas of Ware Creek WMA slated for Restore the Wild-funded projects.

The dominant invasive species are now tree of heaven, privet ligustrum spp., stiltgrass, Johnson grass, and sorghum halepense. All of these species easily invade disturbed areas and outcompete native vegetation. Near the agricultural fields, these species have completely beaten out the native plants for the edge habitat between the forests and open fields. Instead of having native plants blending a soft transition from forest to field, these invasive plants cause a sudden shift that doesn’t help wildlife.

These transitional areas between forest and field should have a blend of plants and animal occupants from both areas, creating an area of high biodiversity known as the “edge effect.” These areas provide cover from predators and variation in food crops that either forest or field might not have enough of due to lack of light in the closed forest canopy or due to competition in the field. Unfortunately, these non-native species are too well adapted to the edge and have prevented the natural succession process and created near monocultures of invasive species. These field edges are also important because they provide a higher quantity of forbs, and fruiting plants like ragweed, beggar’s lice, beautyberry, coralberry, mulberry, etc.

Many of the Restore the Wild projects have an extended timeline, with work happening throughout 2023 and into 2024. Wildlife Area Managers overseeing Restore the Wild-funded projects are required to submit before-and-after photos of their project sites.