Spotted skunk in a towel. Photo by Emily Thorne.

Spotted skunks make use of many different environments for their dens! This one has dug out a den underneath a fallen tree. Photo by Emily Thorne.

Spotted skunks are avid climbers. Photo by Shutterstock.

Spotted skunk. Photo by Emily Thorne.

Fact File

Scientific Name: Spilogale putorius putorius

Classification: Mammal, Order Carnivora, Family Mephitidae

Relatives: Weasels (distant), hog-nosed skunks, striped skunks, other spotted skunk species

Conservation Status:

- SGCN Tier IVc: The Virginia 2015 Wildlife Action Plan lists the Eastern Spotted Skunk as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) in Tier 4, with a conservation opportunity ranking of "c"

- Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List

Size: Tail length excluded, adult eastern spotted skunks average 9 – 13.5 inches in length; males weigh 1 to 2.2 pounds and females weigh 0.8 to 1.2 pounds.

Life Span: Unknown in the wild, up to 10 years in captivity.

Identifying Characteristics

Photo by Grayson Smith / USFWS.

About half the size of a house cat, this is one of the smallest skunks, with short legs and a long, bushy tail with a white tip. It has a black coat with four broken white stripes, and white patches in front of the ears and on the forehead above the nose. Like its distant relative the weasel, it has a long, tube-like shape. In addition to this unique appearance, the spotted skunk has a characteristic handstand defense mechanism that makes it appear larger.

Habitat

Established fields, young forests with lots of scrubby plants, and mature forests with rhododendron and laurel thickets.

Diet

Insects, small mammals, bird eggs, bees and honey.

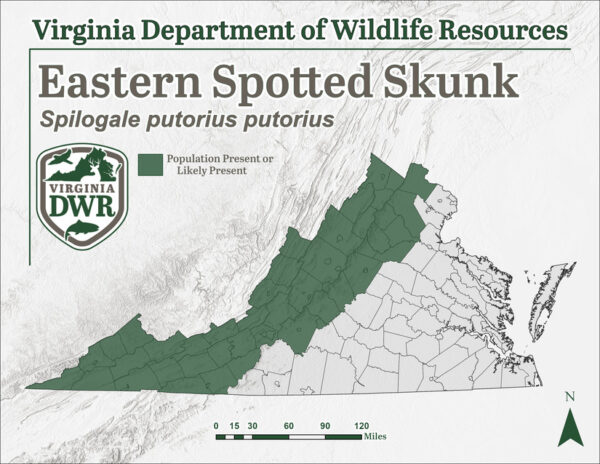

Distribution:

The eastern spotted skunk ranges from the upper reaches of the Great Plains into the northern Gulf coast of Mexico and up the spine of the Appalachian Mountains into Pennsylvania. Within Virginia, they are found in the foothills of the Blue Ridge and further west.

Role in the Web of Life

The spotted skunk’s diet features heavy seasonal variation. They eat mostly insects in the summer and fall months but shift to small mammals in the winter and spring. Foods include beetles, grubs, bees and honey, mice, moles, rats, chipmunks, bird eggs, and fresh carrion. They crack eggs by propelling them against an object with the hind feet.

As voracious predators of insects and small mammals, they keep ecosystems in balance and control pests that could enter our homes.

Spotted skunks are eaten by larger carnivores including coyotes, bobcats, and great horned owls. Great horned owls are the deadliest, swooping down on them when they cross open patches of forest.

The Den: Refuge and Reproduction

For spotted skunks, the den is a key refuge from predators and stressful environmental conditions, as well as a safe place to raise their young. They excavate underground dens themselves or take over dens abandoned by other animals, including woodrats and long-tailed weasels. Dens typically have two to five entrances with between one and three nest chambers.

Due to their tube-like shape, spotted skunks have a high surface area-to-volume ratio, which causes them to lose heat quickly. On cold nights, instead of foraging, they stay in their dens to conserve heat. There is no true hibernation, just short inactive periods in the winter to conserve body fat.

Female spotted skunks used these underground burrows primarily when they have young litters. During other seasons, they’ve been known to den in tree cavities, sometimes as high as 20 feet in a hardwood tree. When raising mobile juveniles, female skunks move the litter to a rocky outcrop habitat. This variety of habitat usage dependent on weather and breeding season makes spotted skunks unique.

Spotted skunks mate by April, and between two and six young are born during May or June. The male gives no care to the young.

Life at Night

Spotted skunk leaving its den at night. Photo by Rick Reynolds / DWR.

Eastern spotted skunks are nocturnal, foraging for food at night and remaining in the den during the day. This behavior helps them to avoid predators and reduce competition with other species. On rainy nights, spotted skunks become more active, due to a higher abundance of insect and mammal prey outside.

Did You Know?

The spotted skunk’s characteristic (and ominous) handstand defense. Photo by Agnieszka Bacal / Shutterstock.

When spotted skunks feel threatened, they will go into a handstand to appear larger and more intimidating. If the handstand doesn’t serve as enough of a deterrent, they can spray foul-smelling musk at their target, up to 13 feet away!

Spotted skunk climbing an apple tree. Photo by Shutterstock.

In addition to their unique defense mechanism, spotted skunks are the only skunks known to climb trees!

Where to See in Virginia

Due to its nocturnal habits and rugged habitats, spotted skunks are hard to find, even if you live in the Blue Ridge or points west. We recommend checking your wildlife cameras for the best chance at a glimpse of this elusive animal.

If you do encounter one in-person, enjoy it from a safe distance and be careful not to disturb it. Your chances of being sprayed are minimal.

Conservation

Before the 1940s, the eastern spotted skunk was abundant across its range, but in the last 80 years its populations have plummeted. The drivers of this collapse are not well understood, and most of them have not been studied systematically. Habitat loss, poisoning from insecticides, and competition with other small carnivores (such as raccoon, bobcat, and coyote) may all play a role. In addition, due to their small size and nocturnal habits, spotted skunks are sometimes killed when crossing roads.

Because the eastern spotted skunk is so elusive, research is the focus of DWR’s conservation work. Recent studies of spotted skunk habitat have taken place outside of Virginia, and so we are challenged to figure out to what extent that research applies to our population of spotted skunks.

To improve our understanding of the distribution and behavior of eastern spotted skunks in Virginia, we funded a multi-year PhD thesis study of spotted skunk ecology at Virginia Tech, led by Dr. Emily Thorne and advised by Dr. Mark Ford. This project investigated where and when spotted skunks were denning and foraging using camera-trap surveys and radio-tracking tags. This research has yielded several insights that help us to consider next steps for management:

- Modelling based on detection of spotted skunks predicts the highest probability of occurrence on ridgelines throughout the Appalachian Mountains.

- Focusing on microhabitat details, spotted skunks prefer to live in forests with a complex structure, whether that’s a young forest at lower elevation with lots of saplings and leafy plants, or a mature hardwood forest with thickets of rhododendron and mountain laurel.

- Spotted skunks change den sites frequently in response to changes in the environment and their life cycle—females tend to den in tree cavities during the early spring breeding season, in underground burrows while pregnant, and in underground burrows or rock crevices while raising their kits.

- Spotted skunks occupy many of the same spaces as other small carnivores but minimize competition by foraging for food at night.

How You Can Help

Become a Restore the Wild member to support habitat restoration, access recreational opportunities at all Wildlife Management Areas and DWR lakes, and enjoy art inspired by Virginia’s incredible wildlife!

Support the maintenance of spotted skunk habitat on your property by managing forests for complex structure.

Learn to coexist with spotted skunks—deter them from your house by properly securing trash and pet food and otherwise let them be—they will control pests for you! Check out this document to learn more about living with skunks and other small mammals in residential areas. Please note that it’s illegal to trap or shoot spotted skunks in Virginia (unless they are causing damage) and their pelts may not be sold. If a wildlife conflict is unresolvable, you may consult a list of licensed trappers and Commercial Nuisance Animal Permit (CNAP) holders who can assist you.

More Information

Seeing Spots: The search for Virginia’s Extraordinary Little Stinkers – Virginia Master Naturalists

Spotted Skunk Study Underway | Virginia DWR

Spatial Ecology of a Vulnerable Species: Home Range Dynamics, Resource Use, and Genetic Differentiation of Eastern Spotted Skunks in Central Appalachia (vt.edu) by Dr. Emily Thorne (research funded by DWR)

Sources

Gompper, M. & Jachowski, D. 2016. Spilogale putorius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41636A45211474. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41636A45211474.en.

Kinlaw, A. 1995. Spilogale putorius. Mammalian Species 511: 1-7. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3504212 Accessed online 7/7/2023.

Burt, W.H., 1964, A field guide to the mammals: North America north of Mexico, 284 pgs., The Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. Accessed online 7/7/2023.

Handley, C.O., Jr., Patton, C.P., 1947, Wild Mammals of Virginia, 220 pgs., Virginia Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries, Richmond, VA. Accessed online 7/7/2023.

Thorne, E.D. 2020. Spatial Ecology of a Vulnerable Species: Home Range Dynamics, Resource Use, and Genetic Differentiation of Eastern Spotted Skunks in Central Appalachia. PhD Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/105619. Accessed online 7/7/2023.

Kassandra J. Arts, M. Keith Hudson, Nicholas W. Sharp, Andrew J. Edelman “Eastern Spotted Skunks Alter Nightly Activity and Movement in Response to Environmental Conditions,” The American Midland Naturalist, 188(1), 33-55, (10 August 2022)

Damon B. Lesmeister, Joshua J. Millspaugh, Matthew E. Gompper, Tony W. Mong “Eastern Spotted Skunk (Spilogale putorius) Survival and Cause-specific Mortality in the Ouachita Mountains, Arkansas,” The American Midland Naturalist, 164(1), 52-60, (1 July 2010)

Gompper, M. E., & Hackett, H. M. (2005). The long-term, range-wide decline of a once common carnivore: the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius). Animal Conservation forum, 8(2), 195–201. Cambridge University Press.

Thorne, E.D. 2016. Seeing Spots: The search for Virginia’s Extraordinary Little Stinkers – Virginia Master Naturalists. Accessed online 7/7/2023.

ADW: Spilogale putorius: INFORMATION (animaldiversity.org). University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed online 7/10/2023.

Thorne, E. D., and W. M. Ford. 2022. Redundancy analysis reveals complex den use patterns by eastern spotted skunks, a conditional specialist. Ecosphere 13.

Thorne, E. D., and W. M. Ford. 2021. Predicted Spatial Distribution of the Eastern Spotted Skunk (Spilogale putorius) in Virginia Using Detection and Non-Detection Records. Southeastern Naturalist 20.

Species Profile Authors: Joshua Murray, DWR Wildlife Action Plan Intern, and Jessica Ruthenberg, DWR Watchable Wildlife Biologist

Last updated: March 10, 2024

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources Species Profile Database serves as a repository of information for Virginia’s fish and wildlife species. The database is managed and curated by the Wildlife Information and Environmental Services (WIES) program. Species profile data, distribution information, and photography is generated by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, State and Federal agencies, Collection Permittees, and other trusted partners. This product is not suitable for legal, engineering, or surveying use. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources does not accept responsibility for any missing data, inaccuracies, or other errors which may exist. In accordance with the terms of service for this product, you agree to this disclaimer.