Red-cockaded Woodpeckers. Photo by Nick Athanas.

Red-cockaded Woodpecker. Photo by Tom Benson.

Red-cockaded Woodpecker at cavity. Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Fact File

Scientific Name: Dryobates borealis

Classification: Bird, Order Piciformes, Family Picidae

Relatives: woodpeckers

Conservation Status:

- Federally Threatened in the U.S.

- State Endangered in Virginia

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need-Tier 1a on the Virginia Wildlife Action Plan

Size: 7.9–9.1 inches long with 14.2 inch wingspan (similar in size to a robin)

Life Span: a few banded birds have lived over 18 years, though this is unusual

Identifying Characteristics

Red-cockaded Woodpecker. Illustration by Naomi McCavitt.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers, also referred to as RCWs, are relatively small black-and-white woodpeckers with distinctive large, white “cheek patches.” Below their cheek patch, they have a heavy black moustache stripe extending downward on either side of the lower bill. Their backs are black with horizontal white bars forming a ladder-like pattern. They have distinctive black spots along the sides of their white bellies. They are approximately the size of an American robin.

A tiny red streak (called a “cockade”), found only on the males, gives the birds their name. The red cockade is located along the top of the white cheek patch, but the bird’s black crown feathers typically conceal this marking.

Apart from the hidden red cockade, the males and females look the same. Juvenile males have a red crown patch on the top of their heads that they lose only a few months after fledging.

Similar-looking species:

Downy woodpecker and hairy woodpecker, which are far more abundant in population, have the following distinguishing features from the rare red-cockaded woodpecker. Both downy and hairy woodpeckers, lack the large white cheek patch of the red-cockaded woodpecker. Instead, both of these common species have a thick black horizontal stripe across their eye that extends to the back of their heads (referred to as an “eye-line”). Both of these species have plain white bellies, whereas the red-cockaded woodpecker has black spotting along the sides of its white belly. Downy and hairy woodpeckers have a thick white stripe down their back, differing from the red-cockaded woodpecker’s back, which is black with ladder-like markings. Furthermore, the downy woodpecker measuring just 5.5-6.7 inches in length is about 2/3 the size of a red-cockaded (7.9-9.1 in.) or hairy woodpecker (7.1-10.2 in.) and has a much smaller bill than either bird.

Habitat

year-round resident of pine savanna (open pine forests maintained by frequent fire); associated with mature longleaf pines and/or loblolly pines that average 70–120 years old; prefers longleaf pines, but will inhabit other pines as well

Diet

primarily insects and other arthropods found on pine trees, especially ants, beetles, and larvae of several species; will also eat some seeds and fruits, such as pine seeds, wild cherry, wild grape and poison ivy, but these constitute a small portion of their overall diet.

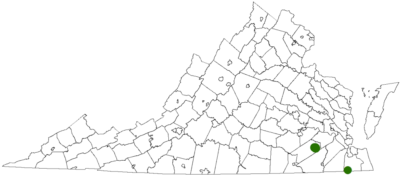

Distribution:

non-migratory; fragmented populations in southeast Virginia’s Sussex County and City of Chesapeake form the northern boundary of its U.S. range and represent a fraction of its historical distribution within the Commonwealth.

Family Matters

Unique amongst most North American woodpeckers, red-cockaded woodpeckers are a social species that live in family groups with a highly developed, cooperative breeding system. This also makes them unique amongst all bird species–only 3% of bird species breed in this manner. Family groups use a group of trees, known as a “cluster”, to develop nesting/ roosting cavities. Family groups generally consist of 2–6 birds with one monogamous breeding pair and 1–4 helpers. The helpers are typically the pair’s male offspring from the previous breeding season, who have delayed their own reproduction in order to help their parents in raising their siblings. The family group grows in size during the course of the breeding season with the hatching and fledging of new young.

Got Cavities?

Red-cockaded woodpecker feeding young at cavity. Photo by John Maxwell, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers excavate their nesting and roosting cavities only in live pine trees.

This behavior distinguishes them from all other woodpecker species, which build their cavities in dead trees or decaying parts of living trees.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers prefer older pine trees that are large enough to sustain a cavity and are often infected with fungi that soften the wood, making it easier for the birds to excavate. The birds also peck tiny holes around their cavities, causing pine resin to flow out and down the tree’s trunk. The pine resin looks like melting white candle wax.

This behavior helps protect their nests because the resin deters climbing snakes.

Role in the Web of Life

Red-cockaded woodpeckers are considered a “keystone species” within the fire-maintained longleaf pine ecosystem. The cavities that the woodpeckers excavate in living pine trees can remain on the landscape for decades, creating shelter and nesting opportunities for 27 other known birds and animals, including American kestrel, eastern screech-owls, and southern flying squirrels.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers may be preyed upon by rat snakes, eastern screech-owls, American kestrels and hawks. In conjunction with other insect-eating birds, the woodpecker’s diet of insects and other arthropods helps keep these populations in check.

Where to See in Virginia

Red-cockaded Woodpecker viewing area in Big Woods Wildlife Management Area. Photo by Lynda Richardson/ DWR.

Big Woods Wildlife Management Area is the only location in Virginia with public access to view red-cockaded woodpeckers.

Although the woodpeckers are also present at Piney Grove Preserve and Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, they do not inhabit their publicly accessible areas.

Conservation

The Road to Recovery

Red-cockaded woodpeckers were once common in the southeastern U.S. with a range that extended north into New Jersey and largely corresponded to the historic range of pine savanna. However, with the large-scale harvesting of these forests that began in the 1800s, woodpecker populations were decimated and they are no longer found in some states that originally formed their range.

Example of pine savanna habitat at Piney Grove Preserve. Photo by Robert B. Clontz/ The Nature Conservancy.

In Virginia, historic records from the early twentieth century document red-cockaded woodpeckers as having ranged as far west as Giles County, as far north as Albemarle County, and throughout the southeastern corner of the state, but by 2002, only 2 breeding pairs remained in the Commonwealth, both at what is now Piney Grove Preserve (PGP) in Sussex County. Red-cockaded woodpecker declines, regionally and in Virginia, were the result of habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation, largely due to large-scale clear-cutting of pine savannas for timber harvesting and agriculture as well as fire suppression during the twentieth century. Fire had a natural, historical, and integral presence in the evolution of pine forest ecosystems in the southeastern U.S. and without it, the open conditions favored by the woodpecker declined.

Although the species was downlisted to federally threatened in October 2024, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) originally listed the species as endangered in 1970, and a national Recovery Plan for the Red-cockaded Woodpecker was developed. The Plan outlines population goals required for recovering the species along with conservation and management guidance on how to reach these goals. Numerous conservation agencies and organizations, including the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR), have implemented this guidance in working towards the birds’ recovery.

Longleaf pine planting at Big Woods WMA. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/ DWR.

A critical conservation strategy has been habitat management—preserving large tracts of mature pine forest, planting longleaf pine, conducting prescribed burns and carefully planned timber harvests to restore pine forests to the open pine savannas upon which the birds depend. The burns are an essential restoration element as they help prevent the encroachment of hardwoods and maintain the open conditions that the woodpeckers favor. However, habitat restoration on its own is not enough; since it can take red-cockaded woodpeckers several months or longer to excavate a cavity in living pine, installing artificial nest cavities has been vital to enhancing clusters and establishing new groups. Additional strategies have included using metal plates to reduce the size of cavity entrances that have become too large for the birds to use, and occasionally translocating individuals to bolster existing populations or establish new populations.

What the DWR Has Done/Is Doing

Under the Endangered Species Act, the DWR has a Cooperative Agreement with the USFWS to serve as the lead agency for the conservation of protected animal species in Virginia, including red-cockaded woodpecker. To help red-cockaded woodpeckers make a comeback in the Commonwealth, the DWR has long supported and contributed to habitat restoration and intensive population management by The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and The Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary (CCB) at PGP.

A DWR biologist working a controlled burn at Big Woods WMA. Photo by Meghan Marchetti/ DWR.

In order to facilitate the expansion of PGP’s population, the DWR acquired and has been restoring habitat for red-cockaded woodpecker at our neighboring property, Big Woods Wildlife Management Area (WMA) since 2011. Beginning in 2015, DWR has also assisted USFWS and other partners with red-cockaded woodpecker reintroduction efforts at Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (GDSNWR).

Through these conservation efforts, DWR and partners have achieved several notable landmarks in the red-cockaded woodpecker’s recovery. From 2002–2017, the woodpecker’s population at PGP increased from 20 to 84 individuals and the number of groups increased from 2 to 13. This increase marked a major milestone in Virginia’s recovery efforts, as achieving 12–13 groups had been set as one of the long-term goals for PGP in the Virginia Red-cockaded Woodpecker Conservation Plan.

Red-cockaded Woodpecker at its nest cavity in Big Woods Wildlife Management Area. Photo by Lynda Richardson/ DWR, 2019.

CCB’s 2017 surveys of PGP and GDSNWR identified a combined total population of 96 individual red-cockaded woodpeckers—at the time, this was the largest population of the species known to occur in Virginia since the early 1980s.

Also in 2017, DWR and TNC biologists discovered a banded male red-cockaded woodpecker with an active cavity on Big Woods WMA. The bird had originated from the PGP population. Although the species historically occurred in Sussex County, this was the first documented occurrence of an individual or cavity on the WMA, demonstrating that the DWR’s restoration efforts are making a difference and PGP’s woodpeckers are finding the expanded habitat they need. Conservation and management at all three of these properties is ongoing. DWR and partners are optimistic that long-term efforts will eventually help maintain and increase red-cockaded woodpeckers towards a more robust and resilient population.

Learn More About Our Work

- Wrap-up of 2020 Red-cockaded Woodpecker Season at Big Woods WMA (2020)

- Banding Red-cockaded Woodpeckers at Big Woods WMA (2020)

- A New Red-cockaded Woodpecker Nest at Big Woods! (2020)

- Red-cockaded Woodpecker Chicks Fledge Nest at Big Woods WMA (2019)

- First Nestlings of the Endangered Red-cockaded Woodpecker Hatched on Big Woods Wildlife Management Area (2019)

- Foraging New Ground: A Pair of Endangered Woodpeckers Has Found a New Home in Big Woods Wildlife Management Area (2019)

- Restoring the Red-cockaded Woodpecker in Virginia (2016)

- Endangered Woodpeckers Return to Great Dismal Swamp After 40-Year Absence (2015)

Watch: Restoring Wildlife Habitat Using Prescribed Fire at Big Woods WMA

How You Can Help

Purchase a Restore the Wild Membership to support the DWR’s habitat restoration work, such as that accomplished at Big Woods WMA. The membership also serves as your pass to visiting Big Woods WMA and over 40 other WMAs throughout the Commonwealth.

Purchase a Restore the Wild Membership to support the DWR’s habitat restoration work, such as that accomplished at Big Woods WMA. The membership also serves as your pass to visiting Big Woods WMA and over 40 other WMAs throughout the Commonwealth.- Donate to DWR’s Non-game Fund to support research and conservation of Virginia’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need, like the red-cockaded woodpecker, as well as conservation education and wildlife viewing recreation.

- If visiting red-cockaded woodpecker viewing areas, such as at Big Woods WMA, please stay out of the marked nesting cavity clusters. Do not approach, pursue the birds, or play audio callback recordings—all of which are considered harassment of this endangered species.

- Consider participating in a Safe Harbor Agreement, if you are a landowner with property adjacent to Piney Grove Preserve, Big Woods WMA, or Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge.

Sources

Audubon: Guide to North American Birds (on-line). Red-cockaded Woodpecker. Accessed July 24, 2018 at https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/red-cockaded-woodpecker.

BirdLife International. (2017). Leuconotopicus borealis (amended version of 2017 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22681158A119170967. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22681158A119170967.en. Downloaded on 17 July 2018.

Blanc, L.A. and J.R. Walters. (2008). Cavity-Nest Webs in a Longleaf Pine Ecosystem. The Condor 110(1): 80-92. The Cooper Ornithological Society.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2017). Downy Woodpecker, All About Birds.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2017). Hairy Woodpecker, All About Birds.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2017). Red-cockaded Woodpecker, All About Birds.

Jackson, J. A. (1994). Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.85

Pool, N. (2014). Picoides borealis (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 17, 2018 at http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Picoides_borealis/

Texas A&M Forest Service. Forest Resources: Red-Cockaded Woodpecker. Accessed July 20, 2018 at http://texasforestservice.tamu.edu/uploadedFiles/TFSMain/Manage_Forest_and_Land/Landowner_Assistance/Stewardship(1)/Red-Cockaded_Woodpecker.pdf

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (2008). Red-cockaded Woodpecker: Picoides borealis.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2003. Recovery plan for the red-cockaded woodpecker

(Picoides borealis): second revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, GA. 296 pp.

Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources. (2016). Restoring the Red-cockaded Woodpecker in Virginia, VDWR Blog.

Watts, Bryan. (2018). A Good Year for Woodpeckers, Center for Conservation Biology. Accessed July 31, 2018.

Watts, B.D. and S.R. Harding. (2007). Virginia Red-cockaded Woodpecker Conservation Plan. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-07-07. College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. 42 pp.

Watts, B. D., F. M. Smith, B. J. Paxton and M. Pavlosky, Jr. (2017). Investigation of Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in Virginia: Year 2017 report. Center for Conservation Biology Technical Report Series, CCBTR-17-17. College of William and Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University, Williamsburg, VA. 18 pp

Species Profile Authors: Sergio Harding, DWR Non-game Bird Conservation Biologist, and Jessica Ruthenberg, DWR Watchable Wildlife Biologist

Last updated: December 10, 2025

The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources Species Profile Database serves as a repository of information for Virginia’s fish and wildlife species. The database is managed and curated by the Wildlife Information and Environmental Services (WIES) program. Species profile data, distribution information, and photography is generated by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, State and Federal agencies, Collection Permittees, and other trusted partners. This product is not suitable for legal, engineering, or surveying use. The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources does not accept responsibility for any missing data, inaccuracies, or other errors which may exist. In accordance with the terms of service for this product, you agree to this disclaimer.