Montebello Fish Cultural Station is a popular location to watch trout rearing.

By Dr. Peter Brookes

Photos by Meghan Marchetti

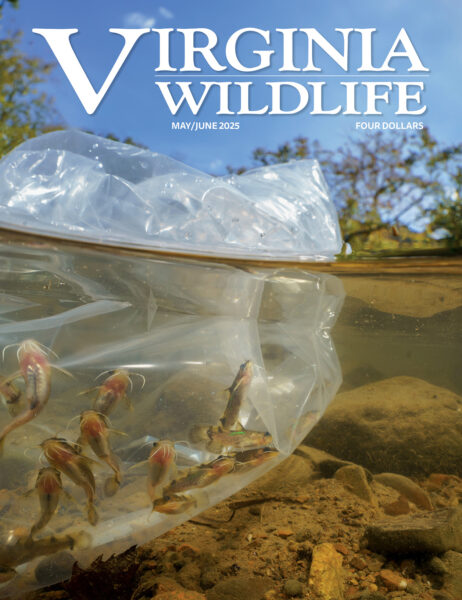

You’ve got to hatch ‘em to catch ‘em! The Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources (DWR) maintains a robust network of fish hatcheries to keep Virginia’s waters teeming with rainbow, brook, and brown trout in addition to bluegill, redear sunfish, walleye, musky, crappie, saugeye, and striped bass. Over the last eight years, DWR stocked Virginia waters with nearly 15,000,000 freshwater fish. Annually, DWR stocks approximately 1 million catch-able-size trout in some 180 waters around the state.

“What we’re concentrating on is the production of game fish for re-stocking, for creation of sport-fishing opportunities, or perhaps to rebuild populations because of natural conditions,” said Brendan Delbos, DWR State Aquaculture Coordinator. Many fish populations in the major sport fisheries in Virginia either rely on annual stockings from hatcheries to maintain their numbers or were started with hatchery fish and then sustained by natural reproduction.

A bird’s-eye view of the King and Queen Hatchery.

DWR operates four warmwater hatcheries (King and Queen in King and Queen County, Front Royal in Warren County, Buller in Smyth County, and Vic Thomas in Campbell County) where hatchery technicians and biologists rear and stock a wide variety of species. There are also five coldwater hatcheries devoted to raising and releasing trout: Marion in Smyth County, Paint Bank in Craig County, Wytheville in Wythe County, Coursey Springs in Bath County, and Montebello in Nelson County. “On the trout side, we’re producing and releasing a catch-able-size fish, generally 10 inches and larger. You need a trout license to participate in the put-and-take trout program. On the warmwater side, we’re raising and stocking juvenile fish, fingerlings,” Delbos said.

If you’re interested in discovering what goes into raising and releasing fish, plan a trip to visit a DWR hatchery. The hatcheries are open to the public between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m., with the coldwater hatcheries welcoming visitors seven days a week and the warmwater facilities available to visit Monday through Friday. Please call ahead to the hatchery to coordinate a visit.

The coldwater trout hatcheries will be hosting an open house on May 30. The open houses are great opportunities to meet with DWR hatchery specialists, tour the facilities, and see specialized equipment, such as a stocking truck. You might even get to throw some fish food at a holding pond brimming with trout.

A hatchery technician checks development of walleye embryos in incubators at the Vic Thomas Striped Bass Hatchery.

Warmwater hatcheries use brood stock from the wild. When fish in the wild are ready to spawn, they’re collected and brought back to the hatchery. Coldwater hatcheries rely on resident brood stock. Once the fish spawn, their fertilized eggs are incubated using specialized equipment and techniques. Once hatched and large enough, the fish are transferred to spacious, fertilized outdoor ponds. The fish grow in the ponds anywhere from 30 to 90 days until hatchery staff determine they’re of an appropriate size for release, which depends on the species.

“It’s a fine line,” said Delbos. “We don’t want the fish to be too small when we harvest them, but if they’re too large, they compete with each other in the pond. Finding that balance is when the experience of our staff really comes into play.” The fish are netted from the ponds, transferred to a stocking truck, and transported to the water where they’re released.

Join us at the coldwater trout hatcheries open house on May 30 from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

Hatching and raising fish in a hatchery is “trying to re-create nature,” Delbos said. “It’s very labor-intensive. We’re monitoring the ponds constantly for water quality, temperature, oxygen levels, algae levels, and more. Additionally, we’re monitoring the growth and health of the fish. It’s a very dynamic field. Someone who’s successful in this field knows about biology, chemistry, and physics. They put all that knowledge together to grow fish. We’re also always trying to refine these techniques.”

Hatchery staff work closely with DWR aquatic biologists to determine fish-stocking needs in various waters. “Biologists use various techniques to sample the fish to identify not only the species that are in the water, but also the general health of the various populations,” said Delbos. “They might go to Kerr Reservoir and conduct their sampling and have a low return for striped bass. They’ll tell us, ‘The population really needs some help; let’s bump up our stocking activities for the coming year.’ There’s a lot of interaction and back and forth between the hatcheries and our aquatic biologists.”

The ultimate goal for those involved in raising fish is to have healthy, plentiful fish populations for anglers to enjoy. Whether it’s a beautiful rainbow trout caught on a fly in southwest Virginia or a striped bass reeled in from a lake in eastern Virginia, there’s a good chance that fish spent time growing in a DWR hatchery.

Find out more about DWR’s fish hatcheries and fish stocking!

Dr. Peter Brookes is a part-time, Virginia outdoor writer with a full-time job in Washington, D.C. in foreign policy. BrookesOutdoors@gmail.com

In 1930, DWR began a trout-stocking program that is still going strong today.

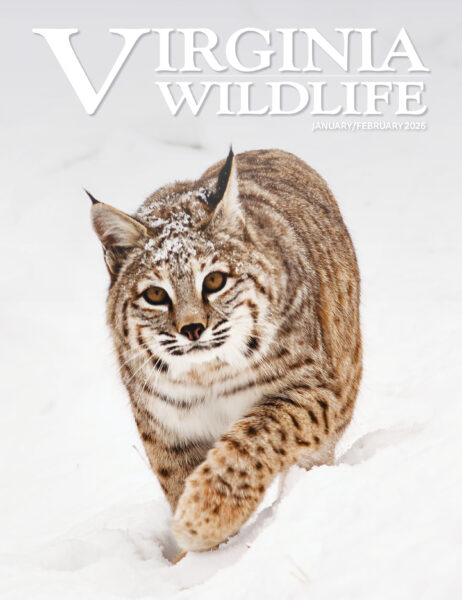

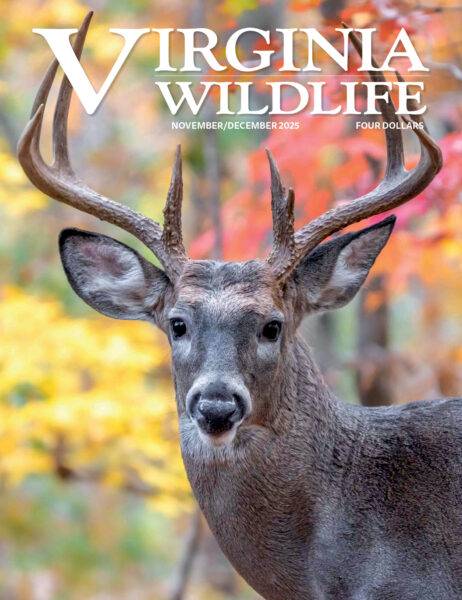

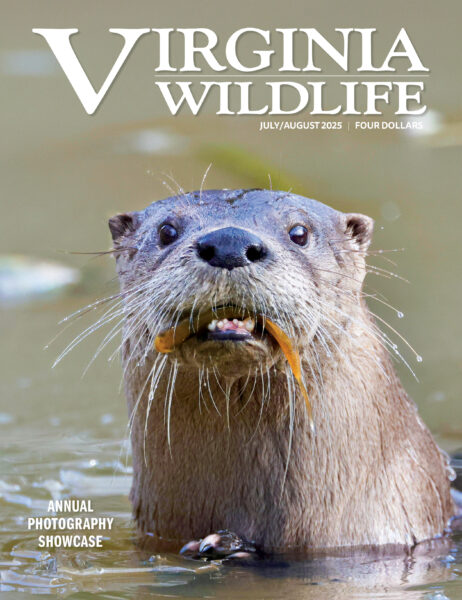

This article originally appeared in Virginia Wildlife Magazine.

For more information-packed articles and award-winning images, subscribe today!

Learn More & Subscribe